https://www.ranker.com/list/maps-mash-v1/mel-judson?format=slideshow&slide=25

Category Archives: Social Determinants of Health

New CDC Report Says Nearly Half of U.S. Population Is at Risk of Contracting Severe COVID-19

Chronic conditions put nearly half of US adults at risk for severe COVID-19

About 47% of US adults have an underlying condition strongly tied to severe COVID-19 illness, researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have found.

The model-based study, published today in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, used self-reported data from the 2018 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System and the US Census.

Researchers analyzed the data for the prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), heart disease, diabetes, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and obesity in residents of 3,142 counties in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. They defined obesity as having a body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m2 or higher.

They found that prevalence patterns generally followed population distributions, with high numbers in large cities, but that these conditions were more prevalent in rural than in urban areas. Counties with the highest prevalence of these conditions were generally clustered in the Southeast and Appalachia.

Severe COVID-19 disease, requiring hospitalization, intensive care, and mechanical ventilation or leading to death, is most common in people of advanced age and in those who have at least one of the previously mentioned underlying conditions.

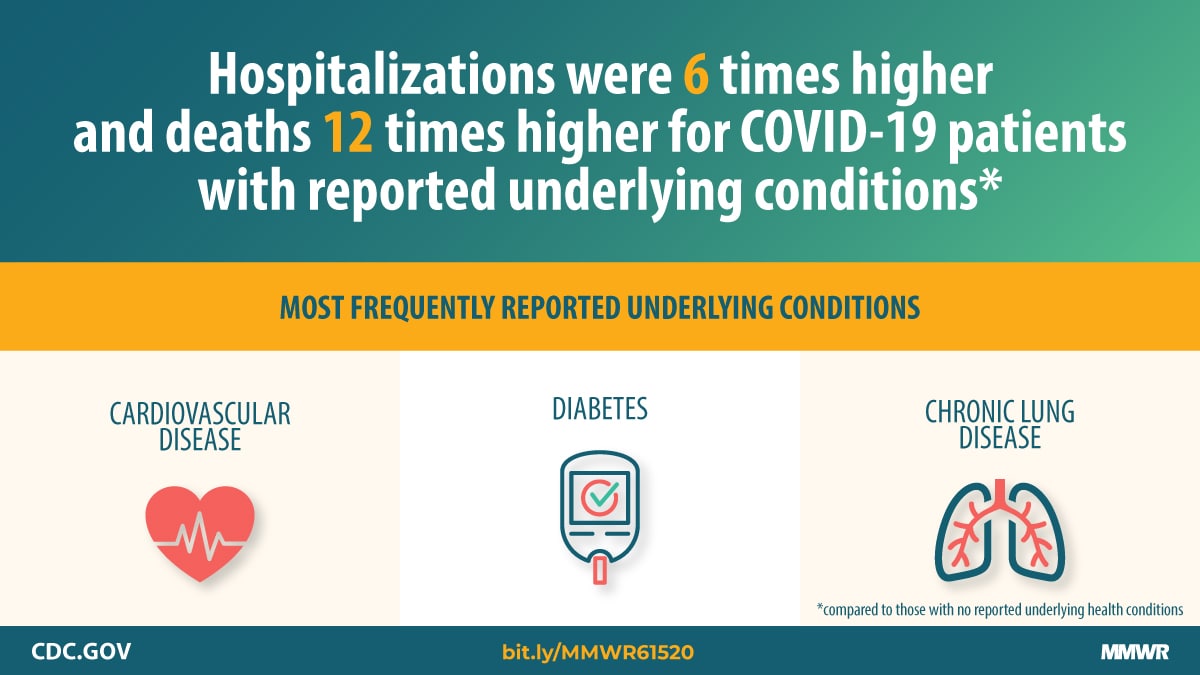

A CDC analysis last month of US COVID-19 patient surveillance data from Jan 22 to May 30 showed that those with underlying conditions were hospitalized six times more often, needed intensive care five times more often, and had a death rate 12 times higher than those without these conditions. But the authors of today’s reported noted that the earlier study defined obesity as a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or higher and included some conditions with mixed or limited evidence of a tie to poor coronavirus outcomes.

Prevalence of underlying conditions in rural, urban counties

Median estimated county prevalence of any underlying illness was 47.2% (range, 22.0% to 66.2%). Numbers of people with any underlying condition ranged from 4,300 in rural counties to 301,744 in large cities.

Prevalence of obesity was 35.4% (range, 15.2% to 49.9%), while it was 12.8% for diabetes (range, 6.1% to 25.6%), 8.9% for COPD (range, 3.5% to 19.9%), 8.6% for heart disease (range, 3.5% to 15.1%), and 3.4% for CKD, 3.4% (range, 1.8% to 6.2%).

Nationwide, the overall weighted prevalence of adults with chronic underlying conditions was 30.9% for obesity, 11.4% for diabetes, 6.9% for COPD, 6.8% for heart disease, and 3.1% for CKD.

The estimated median prevalence of any underlying condition generally increased with increasing county remoteness, ranging from 39.4% in large metropolitan counties to 48.8% in rural ones.

Resource allocation, preventive health measures

The authors noted that access to healthcare resources in some rural counties may be poor, adding to the risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes.

“The findings can help local decision-makers identify areas at higher risk for severe COVID-19 illness in their jurisdictions and guide resource allocation and implementation of community mitigation strategies,” they wrote. “These findings also emphasize the importance of prevention efforts to reduce the prevalence of these underlying medical conditions and their risk factors such as smoking, unhealthy diet, and lack of physical activity.”

The researchers called for future studies to include the weighting of the contribution of each underlying illness according to the risk of serious COVID-19 outcomes and identifying and integrating other factors leading to susceptibility to both infection and serious outcomes to better estimate the number of people at increased risk for COVID-19 infection.

Diabetes highlights two Americas: One where COVID is easily beaten, the other where it’s often devastating

Dr. Anne Peters splits her mostly virtual workweek between a diabetes clinic on the west side of Los Angeles and one on the east side of the sprawling city.

Three days a week she treats people whose diabetes is well-controlled. They have insurance, so they can afford the newest medications and blood monitoring devices. They can exercise and eat well. Those generally more affluent West L.A. patients who have gotten COVID-19 have developed mild to moderate symptoms – feeling miserable, she said – but treatable, with close follow-up at home.

“By all rights they should do much worse, and yet most don’t even go to the hospital,” said Peters, director of the USC Clinical Diabetes Programs.

On the other two days of her workweek, it’s a different story.

In East L.A., many patients didn’t have insurance even before the pandemic. Now, with widespread layoffs, even fewer do. They live in “food deserts,” lacking a car or gas money to reach a grocery store stocked with fresh fruits and vegetables. They can’t stay home, because they’re essential workers in grocery stores, health care facilities and delivery services. And they live in multi-generational homes, so even if older people stay put, they are likely to be infected by a younger relative who can’t.

They tend to get COVID-19 more often and do worse if they get sick, with more symptoms and a higher likelihood of ending up in the hospital or dying, said Peters, also a member of the leadership council of Beyond Type 1, a diabetes research and advocacy organization.

“It doesn’t mean my East Side patients are all doomed,” she emphasized.

But it does suggest COVID-19 has an unequal impact, striking people who are poor and already in ill health far harder than healthier, better off people on the other side of town.

Tracey Brown has known that for years.

“What the COVID-19 pandemic has done is shined a very bright light on this existing and pervasive problem,” said Brown, CEO of the American Diabetes Association. Along with about 32 million others – roughly 1 in 10 Americans – Brown has diabetes herself.

“We’re in 2020, and every 5 minutes, someone is losing a limb” to diabetes, she said. “Every 10 minutes, somebody is having kidney failure.”

Americans with diabetes and related health conditions are 12 times more likely to die of COVID-19 than those without such conditions, she said. Roughly 90% of Americans who die of COVID-19 have diabetes or other underlying conditions. And people of color are over-represented among the very sick and the dead.

Diabetes increases COVID risk

The data is clear: People with diabetes are at increased risk of having a bad case of COVID-19, and diabetics with poorly controlled blood sugar are at even higher risk, said Liam Smeeth, dean of the faculty of epidemiology and population health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. He and his colleagues combed data on 17 million people in the U.K. to come to their conclusions.

Diabetes often comes paired with other health problems – obesity and high blood pressure, for instance. Add smoking, Smeeth said, and “for someone with diabetes in particular, those can really mount up.”

People with diabetes are more vulnerable to many types infections, Peters said, because their white blood cells don’t work as well when blood sugar levels are high.

“In a test tube, you can see the infection-fighting cells working less well if the sugars are higher,” she said.

Peters recently saw a patient whose diabetes was triggered by COVID-19, a finding supported by one recent study.

Going into the hospital with any viral illness can trigger a spike in blood sugar, whether someone has diabetes or not. Some medications used to treat serious cases of COVID-19 can “shoot your sugars up,” Peters said.

In patients who catch COVID-19 but aren’t hospitalized, Peters said, she often has to reduce their insulin to compensate for the fact that they aren’t eating as much.

Low income seems to be a risk factor for a bad case of COVID-19, even independent of age, weight, blood pressure and blood sugar levels, Smeeth said. “We see strong links with poverty.”

Some of that is driven by occupational risks, with poorer people unable to work from home or avoid high-risk jobs. Some is related to housing conditions and crowding into apartments to save money. And some, may be related to underlying health conditions.

But the connection, he said, is unmistakable.

Peters recently watched a longtime friend lose her husband. Age 60 and diabetic, he was laid off due to COVID, which cost him his health insurance. He developed a foot ulcer that he couldn’t afford to treat. He ignored it until he couldn’t stand anymore and then went to the hospital.

After surgery, he was released to a rehabilitation facility where he contracted COVID. He was transferred back to the hospital, where he died four days later.

“He died, not because of COVID and not because of diabetes, but because he didn’t have access to health care when he needed it to prevent that whole process from happening,” Peters said, adding that he couldn’t see his family in his final days and died alone. “It just breaks your heart.”

Taking action on diabetes– personally and nationally

Now is a great time to improve diabetes control, Peters added. With many restaurants and most bars closed, people can have more control over what they eat. No commuting leaves more time for exercise.

That’s what David Miller has managed to do. Miller, 65, of Austin, Texas, said he has stepped up his exercise routine, walking for 40 minutes four mornings a week at a nearby high school track. It’s cool enough at that hour, and the track’s not crowded, said Miller, an insurance agent, who has been able to work from home during the pandemic. “That’s more consistent exercise than I’ve ever done.”

His blood sugar is still not where he wants it to be, he said, but his new fitness routine has helped him lose a little weight and bring his blood sugar under better control. Eating less remains a challenge. “I’m one of those middle-aged guys who’s gotten into the habit of eating for two,” he said. “That can be a hard habit to shake.”

Miller said he isn’t too worried about getting COVID-19.

“I’ve tried to limit my exposure within reason,” he said, noting that he wears a mask when he can in public. “I honestly don’t feel particularly more vulnerable than anybody else.”

Smeeth, the British epidemiologist, said even though they’re at higher risk for bad outcomes, people with diabetes should know that they’re not helpless.

“The traditional public health messages – don’t be overweight, give up smoking, keep active – are still valid for COVID,” he said. Plus, people with diabetes should prioritize getting a flu vaccine this fall, he said, to avoid compounding their risk.

(For more practical recommendations for those living with diabetes during the pandemic, go to coronavirusdiabetes.org.)

In Los Angeles, Peters said, the county has made access to diabetes medication much easier for people with low incomes. They can now get three months of medication, instead of only one. “We refill everybody’s medicine that we can to make sure people have the tools,” she said, adding that diabetes advocates are also doing what they can to help people get health insurance.

Controlling blood sugar will help everyone, not just those with diabetes, Peters said. Someone hospitalized with uncontrolled blood sugar takes up a bed that could otherwise be used for a COVID-19 patient.

Brown, of the American Diabetes Association, has been advocating for those measures on a national level, as well as ramping up testing in low-income communities. Right now, most testing centers are in wealthier neighborhoods, she said, and many are drive-thrus, assuming that everyone who needs testing has a car.

Her organization is also lobbying for continuity of health insurance coverage if someone with diabetes loses their job, as well as legislation to remove co-pays for diabetes medication.

“The last thing we want to have happen is that during this economically challenged time, people start rationing or skipping their doses of insulin or other prescription drugs,” Brown said. That leads to unmanaged diabetes and complications like ulcers and amputations. “Diabetes is one of those diseases where you can control it. You shouldn’t have to suffer and you shouldn’t have to die.”

COVID-19 More Deadly Than Cancer Itself?

During the recent months of the pandemic, cancer patients undergoing active treatment saw their risk for death increase 15-fold with a COVID-19 diagnosis, real-world data from two large healthcare systems in the Midwest found.

Among nearly 40,000 patients who had undergone treatment for their cancer at some point over the past year, 15% of those diagnosed with COVID-19 died from February to May 2020, as compared to 1% of those not diagnosed with COVID-19 during this same timeframe, reported Shirish Gadgeel, MD, of the Henry Ford Cancer Institute in Detroit.

And in more than 100,000 cancer survivors, 11% of those diagnosed with COVID-19 died compared to 1% of those not diagnosed with COVID-19, according to the findings presented at the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) COVID-19 and Cancer meeting.

“Certain comorbidities were more commonly seen in patients with COVID-19,” said Gadgeel. “This included cardiac arrhythmias, renal failure, congestive heart failure, and pulmonary circulation disorders.”

For their study, Gadgeel and colleagues examined data on 154,585 malignant cancer patients from 2015 to the present day with active cancer or a history of cancer treated at two major Midwestern health systems. Among the 39,790 patients with active disease, 388 were diagnosed with COVID-19 from February 15 through May 13, 2020. For the 114,795 patients with a history of cancer, 412 were diagnosed with COVID-19.

After adjusting for multiple variables, older age (70-99 years) and several comorbid conditions were significantly associated with increased mortality among COVID-19 patients with active cancer:

- Older age: OR 3.4 (95% CI 1.3-9.3)

- Diabetes: OR 3.0 (95% CI 1.5-6.0)

- Renal failure: OR 2.3 (95% CI 1.1-4.9)

- Pulmonary circulation disorders: OR 3.9 (95% CI 1.4-10.5)

In COVID-19 patients with a history of cancer, an increased risk for death was seen for those ages 60 to 69 years (OR 6.3, 95% CI 1.1-35.3), 70 to 99 years (OR 18.2, 95% CI 3.9-84.3), and those with a history of coagulopathy (OR 3.0, 95% CI 1.2-7.6).

Despite Black patients consisting of less than 10% of the total study population, Gadgeel noted that 39.4% of COVID-19 diagnoses in the active cancer group were among Black patients, as were a third of diagnoses in the cancer survivor group.

And the proportion of COVID-19 patients with a median household income below $30,000 was also higher in COVID-19 patients in both groups, he added.

COVID-19 carried a far greater chance for hospitalization, both for patients with active cancer (81% vs 15% for those without COVID-19) as well as those with a history of cancer (68% vs 6%), with higher hospitalization rates among Black individuals and those with a median income below $30,000. Even younger COVID-19 patients (<50 years) saw high rates of hospitalization, at 79% for those with active cancer and 49% for those with a history of the disease.

While few cancer patients without COVID-19 required mechanical ventilation (≤1%) during the study period, 21% of patients with active disease and COVID-19 needed ventilation, as did 14% of those with a history of cancer, with higher rates among those with a history of coagulopathy (36% and 23%, respectively).

CCC-19 Data Triples in Size

Another study presented during the meeting again showed higher mortality rates for cancer patients with COVID-19, with lung cancer patients appearing to be especially vulnerable.

Among 2,749 cancer patients diagnosed with COVID-19, 60% required hospitalization, 45% needed supplemental oxygen, 16% were admitted to the intensive care unit, and 12% needed mechanical ventilation, and 16% died within 30 days, reported Brian Rini, MD, of Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center in Nashville, Tennessee.

“When COVID first started there was a hypothesis that cancer patients could be at adverse outcome risk due to many factors,” said Rini, noting their typically “advanced age, presence of comorbidities, increased contact with the healthcare system, perhaps immune alterations due to their cancer and/or therapy, and decreased performance status.”

Rini was presenting an updated analysis of the COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium (CCC-19), which now includes 114 sites (includes comprehensive cancer centers and community sites) collecting data on cancer patients and their outcomes with COVID-19.

Initial data from the consortium, of about 1,000 patients, were presented earlier this year at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) annual meeting and published in The Lancet. The early analysis showed that use of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin to treat COVID-19 in cancer patients was associated with a nearly threefold greater risk of dying within 30 days.

Notably, in the new analysis, decreased all-cause mortality at 30 days was observed among the 57 patients treated with remdesivir alone, when compared to patients that received other investigational therapies for COVID-19, including hydroxychloroquine (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.41, 95% CI 0.17-0.99) and a trend toward lower mortality when compared to patients that received no other investigational therapies (aOR 0.76, 95% CI 0.31-1.85).

Cancer status was associated with a greater mortality risk. Compared to patients in remission, those with stable (aOR 1.47, 95% CI 1.07-2.02) or progressive disease (aOR 2.96, 95% CI 2.05-4.28) were both at increased risk of death at 30 days.

Mortality at 30 days reached 35% for patients with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 2 or higher, as compared to 4% (aOR 4.22, 95% CI 2.92-6.10).

“As you start to combine these adverse risk factors you get into really high mortality rates,” said Rini, with highest risk seen among intubated patients who were either 75 and older (64%) or had poor performance status (75%).

“There are several factors that are starting to emerge as relating to COVID-19 mortality in cancer patients,” said Rini during his presentation at the AACR COVID-19 and Cancer meeting. “Some are cancer-related, such as the status of their cancer and perhaps performance status, and others are perhaps unrelated, such as age or gender.”

Other factors that were significantly associated with higher mortality included older age, male sex, Black race, and being a current or former smoker, and having a hematologic malignancy.

Findings from the study were simultaneously published in Cancer Discovery.

“Importantly, there were some factors that did not reach statistical significance,” said Rini, including obesity.

“Patients who received recent cytotoxic chemotherapy or other types of anti-cancer therapy, or who had recent surgery were not in the present analysis of almost 3,000 patients at increased risk,” he continued. “I think this provides some reassurance that cancer care can and should continue for these patients.”

For specific cancer types, mortality was highest in lung cancer patients (26%), followed by those with lymphoma (22%), colorectal cancer (19%), plasma cell dyscrasias (19%), prostate cancer (18%), breast cancer (8%), and thyroid cancer (3%).

“The COVID mortality rate in cancer patients appears to be higher than the general population,” said Rini. “Lung cancer patients appear especially vulnerable by our data, as well as TERAVOLT‘s.”

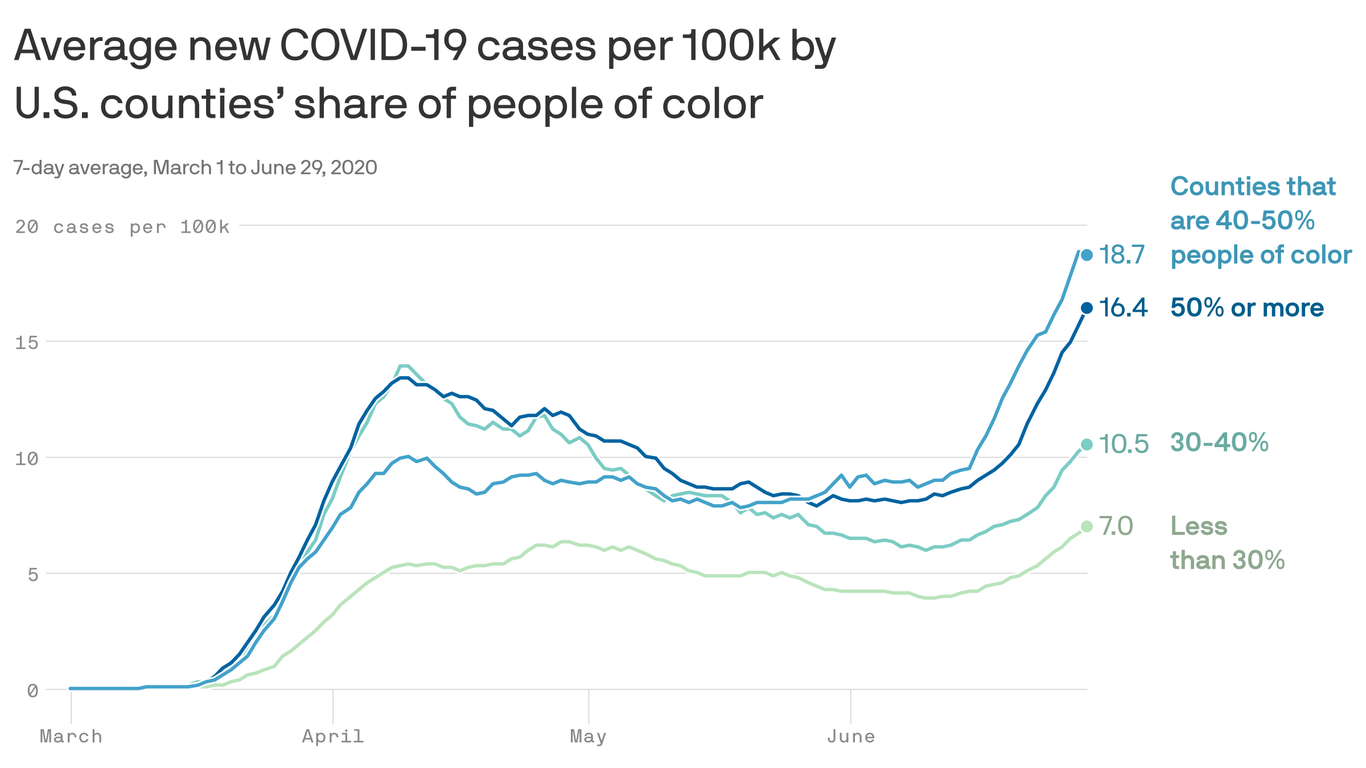

Cases skyrocketing among communities of color

Counties populated by larger numbers of people of color tend to have more coronavirus cases than those with higher shares of white people.

What we’re watching: As the outbreak worsens throughout the South and the West, caseloads are growing fastest in counties with large communities of color.

The big picture: The southern and southwestern parts of the U.S. — the new epicenters of the outbreak — have higher Black and Latino or Hispanic populations to begin with.

- People of color have seen disproportionate rates of infection, hospitalization and death throughout the pandemic.

Between the lines: These inequities stem from pre-existing racial disparities throughout society, and have been exacerbated by the U.S. coronavirus response.

- Black and Hispanic or Latino communities have had less access to diagnostic testing, and people of color are also more likely to be essential workers. That means the virus is able to enter and spread throughout a community without adequate detection, often with disastrous results.

The bottom line: Until we plug the huge holes in the American coronavirus response — like inadequate testing and contact tracing and a lack of protection for essential workers — people of color will continue to bear the brunt of the pandemic.

Go deeper: People of color have less access to coronavirus testing

Coronavirus Doesn’t Recognize Man-Made Borders

From El Centro Regional Medical Center, the largest hospital in California’s Imperial County, it takes just 30 minutes to drive to Mexicali, the capital of the Mexican state of Baja California. The international boundary that separates Mexicali from Imperial County is a bridge between nations. Every day, thousands of people cross that border for work or school. An estimated 275,000 US citizens and green card holders live in Baja California. El Centro Regional Medical Center has 60 employees who reside in Mexicali and commute across the border, CEO Adolphe Edward told Julie Small of KQED.

Now these inextricably linked places have become two of the most concerning COVID-19 hot spots in the US and Mexico. While Imperial County is one of California’s most sparsely populated counties, it has the state’s highest per capita infection rate — 836 per 100,000, according to the California Department of Public Health. This rate is more than four times greater than Los Angeles County’s, which is second-highest on that list. Imperial County has 4,800 confirmed positive cases and 64 deaths, and its southern neighbor Mexicali has 4,245 infections and 717 deaths.

The COVID-19 crisis on the border is straining the local health care system. El Centro Regional Medical Center has 161 beds, including 20 in its intensive care unit (ICU). About half of all its inpatients have COVID-19, Gustavo Solis reported in the Los Angeles Times, and the facility no longer has any available ventilators.

When Mexicali’s hospitals reached capacity in late May, administrators alerted El Centro that they would be diverting American patients to the medical center. “They said, ‘Hey, our hospitals are full, you’re about to get the surge,’” Judy Cruz, director of El Centro’s emergency department, recounted to Rebecca Plevin in the Palm Springs Desert Sun.

By the first week of June, El Centro was so overburdened that “a patient was being transferred from the hospital in El Centro every two to three hours, compared to 17 in an entire month before the COVID-19 pandemic,” Miriam Jordan reported in the New York Times.

Border Hospitals Filled to Capacity

Since April, hospitals in neighboring San Diego and Riverside Counties have been accepting patient transfers to alleviate the caseload at the lone hospital in El Centro, but the health emergency has escalated and now those counties need relief. “We froze all transfers from Imperial County [on June 9] just to make sure that we have enough room if we do have more cases here in San Diego County,” Chris Van Gorder, CEO of Scripps Health, told Paul Sisson in the San Diego Union-Tribune. El Centro patients are now being airlifted as far as San Francisco and Sacramento.

According to the US Census Bureau, nearly 85% of Imperial County residents are Latino, and statewide, Latinos bear a disproportionate burden of COVID-19. The California Department of Public Health reports that Latinos make up 39% of California’s population but 57% of confirmed COVID-19 cases.

Nonessential travel between the US and Mexico has been restricted since March 21, with the measure recently extended until July 21. However, jobs in Southern California, such as in agricultural fields and packing houses, require regular movement between the two countries. “I’m always afraid that people are imagining this rush on the border,” Andrea Bowers, a spokesperson for the Imperial County Public Health Department, told Small. “It’s just folks living their everyday life.”

These jobs, some of which are considered essential because of their role in the food supply chain, may have contributed to the COVID-19 crisis on the border. Agricultural workers often lack access to adequate personal protective equipment and are unable to practice physical distancing. They also are exposed to air pollution, pesticides, heat, and more — long-term exposures that can cause the underlying health conditions that raise the risk of death for COVID-19 patients.

Comite Civico del Valle, a nonprofit focused on environmental health and civic engagement in Imperial Valley, set up 40 air pollution monitors throughout the county and found that levels of tiny, dangerous particulates violated federal limits, Solis reported.

“I can tell you there’s hypertension, there’s poor air pollution, there’s cancers, there’s asthma, there’s diabetes, there’s countless things people here are exposed to,” David Olmedo, an environmental health activist with Comite Civico del Valle, told Solis.

Fear of New Surges

With summer socializing in full swing, health experts worry that COVID-19 spikes will follow. Imperial County saw surges after Mother’s Day and Memorial Day, probably because of lapsed physical distancing and mask use at social events.

Latinos in California are adhering to recommended public health behaviors to slow the spread of the virus. CHCF’s recent COVID-19 tracking poll with Ipsos asked Californians about their compliance with recommended behaviors. Eighty-four percent of Californians, including 87% of Latinos, say they routinely wear a mask in public spaces all or most of the time. Seventy-two percent of Californians, including 73% of Latinos, say they avoid unnecessary trips out of the home most or all of the time, and 90% of Californians, including 91% of Latinos, say they stay at least six feet away from others in public spaces all or most of the time.

A Push to Reopen Anyway

Most counties in California have met the state’s readiness criteria for entering the “Expanded Stage 2” phase of reopening. Imperial County has not. In the past two weeks, more than 20% of all COVID-19 tests in the county came back positive, the Sacramento Bee reported. The state requires counties to have a seven-day testing positivity rate of no more than 8% to enter Expanded Stage 2.

Still, the Imperial County Board of Supervisors is pushing Governor Gavin Newsom for local control over its reopening timetable. The county has a high poverty rate — 24% compared with the statewide average of 13% — and “bills are stacking up,” Luis Pancarte, chairman of the board, said on a recent press call.

He worries that because neighboring areas like Riverside and San Diego have opened some businesses with physical distancing measures in place, Imperial County residents will travel to patronize restaurants and stores. This movement could increase transmission of the new coronavirus, just as reopening Imperial County too soon could as well.

More than 1,350 residents have signed a petition asking Newsom to ignore the Board of Supervisor’s request, Solis reported. The residents called on the supervisors to focus instead on getting the infection rate down and expanding economic relief for workers and businesses.

Cruz, who has been working around the clock to handle the county’s COVID-19 crisis, agrees with the petitioners. The surges after Mother’s Day and Memorial Day made her “really concerned about unlocking and letting people go back to normal,” she told Plevin. “It’s going to be just like those little gatherings that happened [on holidays], but on a bigger scale.”

750 Million Struggling to Meet Basic Needs With No Safety Net

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- One in seven adults worldwide struggle to afford food, shelter with no help

- At least some percentage in every country is “highly vulnerable”

- Highly vulnerable in developed, developing world as likely to have health problems

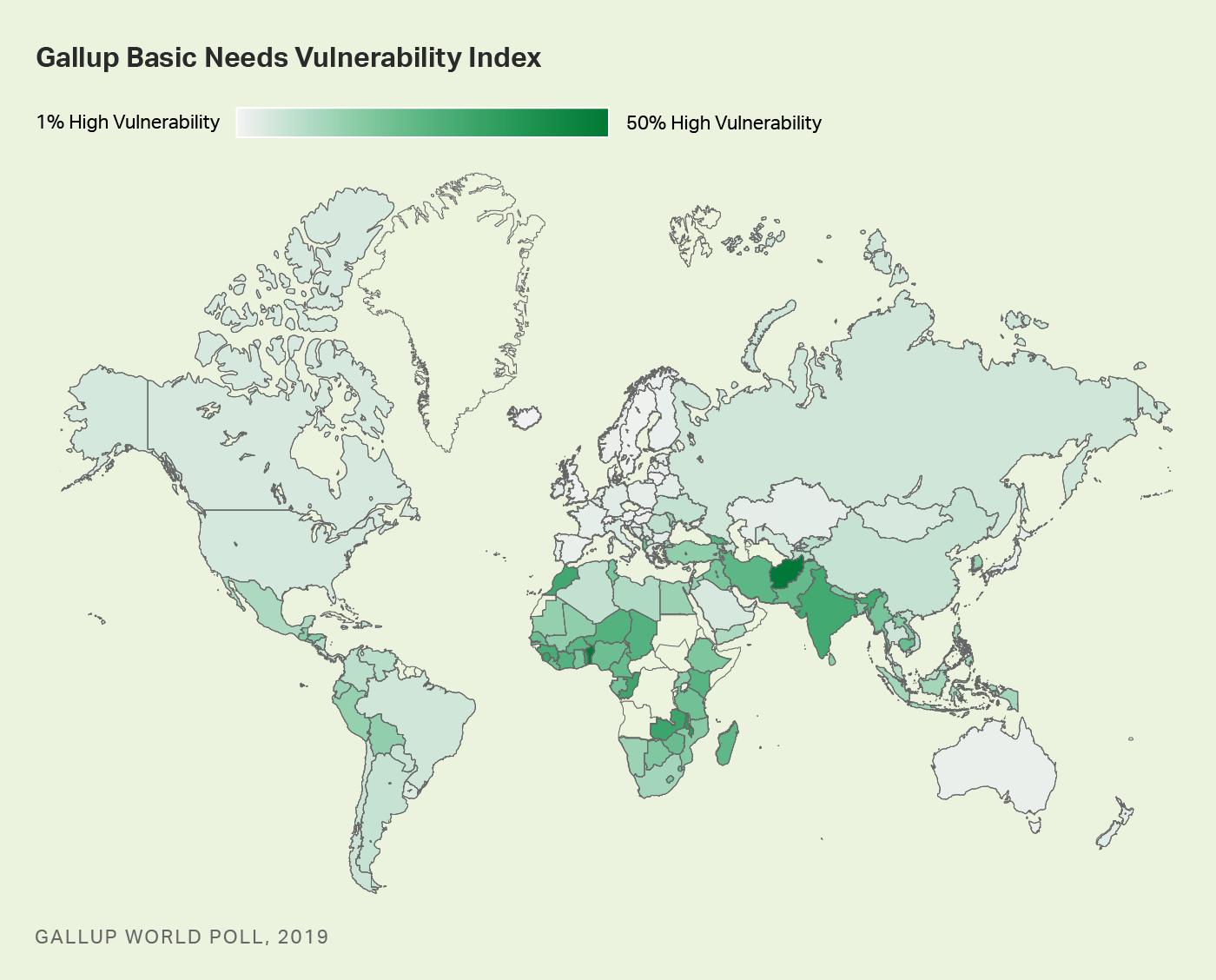

This article is the first in series based on results from Gallup’s new Basic Needs Vulnerability Index.

Imagine being unable to afford food or to put a roof over your head, or maybe you are struggling to do both. On top of this, you don’t have family or friends who can help you.

Now, imagine this is all happening and a pandemic hits.

Gallup’s new Basic Needs Vulnerability Index, based on surveys in 142 countries in 2019, suggests this was the reality for hundreds of millions worldwide just as COVID-19 arrived.

About one in seven of the world’s adults — or about 750 million people — fall into this index’s “High Vulnerability” group, which means they are struggling to afford either food or shelter, or struggling to afford both, and don’t have friends or family to count on if they were in trouble.

Globally, at least some adults in every country fall into the High Vulnerability group, which is important because Gallup finds people in this group are potentially more at risk in almost every area of their lives. Worldwide, these percentages range from 1% in wealthy countries such as Denmark and Singapore to roughly 50% in places such as Benin and Afghanistan.

Gallup’s Basic Needs Vulnerability Index gauges people’s potential exposure to risk from economic and other types of shocks like a pandemic. Beyond measuring people’s ability to afford food and shelter, this index also folds in whether people have personal safety nets — people who can help them when they are in trouble.

People worldwide fall into one of three groups:

High Vulnerability: People in this group say there were times in the past year when they were unable to afford food or shelter or say they struggled to afford both and say they do not have family or friends who could help them in times of trouble.

Moderate Vulnerability: People in this group say there were times in the past year when they were unable to afford food or shelter or say they struggled to afford both, and they do have family or friends to help them in times of trouble.

Low Vulnerability: People in this group say there were not times in the past year when they struggled to afford food or shelter and say they do have family or friends to help them if they were in trouble.

Before the pandemic, most of the world was at least moderately vulnerable, falling into either the High Vulnerability group (14%) or the Moderate Vulnerability group (39%). The rest, 47%, fell into the Low Vulnerability group.

The life experiences in these three groups illustrate the difference that not having family and friends to count on in times of trouble can make in people’s lives.

Highly Vulnerable Most Likely to Experience Health Problems, Experience Pain

While people in the High Vulnerability group are potentially more at risk in almost every area of their lives than those in the other two groups, they are particularly at risk when it comes to their health.

More than four in 10 (41%) of the highly vulnerable say they have health problems that keep them from doing activities that people their age normally do. This percentage drops to 29% among those who are moderately vulnerable and to 14% among those with low vulnerability.

The same is true for experiences of physical pain. The highly vulnerable are also far more likely to say they experienced physical pain the day before the interview (53% have) compared with 37% in the moderately vulnerable and 20% in the lowest vulnerability group.

Looking at who the highly vulnerable are within the global population reinforces why the greater risks to their health are so important. Globally, people in the high vulnerability group are just as likely to be male or female (14% of each fall into this group), and percentages are similar in the 15 to 29 age group (12%) and 60 and older group (14%).

However, the highly vulnerable are more likely to live in rural (16%) rather than urban areas (10%) and be in the poorest 20% of the population (21%) than the richest 20% of the population (7%).

Highly Vulnerable in Developed and Developing Countries Poor Health in Common

As might be expected, most of the countries with the highest percentage in the High Vulnerability group are a mix of developing economies and notably one emerging economy — India — and the countries with the lowest percentage are developed, high-income economies.

However, regardless of where they are located or their level of development, the highly vulnerable populations look a lot alike. In fact, when it comes to health problems, among the highly vulnerable populations, almost the exact same percentage in developing economies (41%) and high-income economies (42%) report having them.

The highly vulnerable in developing countries are only slightly more likely to report experiencing physical pain (53%) than this group in developed, high-income economies (47%).

Implications

As massive as the highly vulnerable group was before the pandemic, it could have been even larger, taking children and other household members into account.

As such, this new layer of vulnerability among populations will be important to monitor as the pandemic threatens to push tens of millions more people into extreme poverty and hunger this year and beyond.

Gladwell: COVID-19 should push healthcare to consider its ‘weak links’

The coronavirus pandemic has shown the healthcare industry that it needs to decide whether it’s playing basketball or soccer, journalist and author Malcolm Gladwell said.

Gladwell, the opening keynote speaker at America’s Health Insurance Plans’ annual Institute & Expo, said the two sports exemplify the differences in thinking when one tackles problems using a “strong link” approach versus a “weak link” approach.

In basketball, he said, the team is as strong as its strongest, most high-profile players. In soccer, by contrast, the team is only as strong as its weakest players.

For healthcare organizations, that means making investments in the “weakest links”—such as harried clinicians who may need more training and low-income communities that cannot afford or access coverage—rather than the stronger links, like building out teaching hospitals and physician specializations.

“In healthcare, this is a chance for us to turn the ship around and say we can benefit far more from making health insurance more plentiful and more affordable,” Gladwell said.

Gladwell emphasized that healthcare is far from the only industry to largely follow a “strong link” approach to improvement. In higher education, for example, much of the investment and funding goes to Ivy League institutions and other wealthy, top-performing universities.

Meanwhile, the education system could see significant benefits if it invested in the “weak links” like community colleges and bringing down tuition, Gladwell said.

It’s a similar story in national security—and that “strong link” thinking led to two of the largest security breaches in American history, Gladwell said. Both Edward Snowden and Chelsea Manning were relatively low-ranking people within the security apparatus, but they were able to access critical files and release them.

“I would argue that ‘strong link’ paradigm has dominated every part of American society,” Gladwell said. “We have really put our chips down on the ‘strong link’ paradigm.”

How could a “weak link” approach have impacted the response to the COVID-19 pandemic? Gladwell argues that, for instance, widespread testing is hampered by a lack of supplies like nasal swabs. Investment in the supply chain could have mitigated that challenge, he said.

The virus also disproportionately impacts people with certain conditions, notably diabetes. A broader focus on preventing and treating obesity could have had a large impact on how the pandemic played out, he said.

“With this particular pandemic, I think we’re having a wake-up call,” Gladwell said.

How America’s Hospitals Survived the First Wave of the Coronavirus

ProPublica deputy managing editor Charles Ornstein wanted to know why experts were wrong when they said U.S. hospitals would be overwhelmed by COVID-19 patients. Here’s what he learned, including what hospitals can do before the next wave.

The prediction from New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo was grim.

In late March, as the number of COVID-19 cases was growing exponentially in the state, Cuomo said New York hospitals might need twice as many beds as they normally have. Otherwise there could be no space to treat patients seriously ill with the new coronavirus.

“We have 53,000 hospital beds available,” Cuomo, a Democrat, said at a briefing on March 22. “Right now, the curve suggests we could need 110,000 hospital beds, and that is an obvious problem and that’s what we’re dealing with.”

The governor required all hospitals to submit plans to increase their capacity by at least 50%, with a goal of doubling their bed count. Hospitals converted operating rooms into intensive care units, and at least one replaced the seats in a large auditorium with beds. The state worked with the federal government to open field hospitals around New York City, including a large one at the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center.

But when New York hit its peak in early April, fewer than 19,000 people were hospitalized with COVID-19. Some hospitals ran out of beds and were forced to transfer patients elsewhere. Other hospitals had to care for patients in rooms that had never been used for that purpose before. Supplies, medications and staff ran low. And, as The Wall Street Journal reported on Thursday, many New York hospitals were ill prepared and made a number of serious missteps.

All told, more than 30,000 New York state residents have died of COVID-19. It’s a toll worse than any scourge in recent memory and way worse than the flu, but, overall, the health care system didn’t run out of beds.

“All of those models were based on assumptions, then we were smacked in the face with reality,” said Robyn Gershon, a clinical professor of epidemiology at the NYU School of Global Public Health, who was not involved in the models New York used. “We were working without situational awareness, which is a tenet in disaster preparedness and response. We simply did not have that.”

Cuomo’s office did not return emails seeking comment, but at a press briefing on April 10, the governor defended the models and those who created them. “In fairness to the experts, nobody has been here before. Nobody. So everyone is trying to figure it out the best they can,” he said. “Second, the big variable was, what policies do you put in place? And the bigger variable was, does anybody listen to the policies you put in place?”

So, why were the projections so wrong? And how can political leaders and hospitals learn from the experience in the event there is a second wave of the coronavirus this year? Doctors, hospital officials and public health experts shared their perspectives.

The Models Overstated How Many People Would Need Hospital Care

The models used to calculate the number of people who would need hospitalization were based on assumptions that didn’t prove out.

Early data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggested that for every person who died of COVID-19, more than 11 would be hospitalized. But that ratio was far too high and decreased markedly over time, said Dr. Christopher J.L. Murray, director of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington. IHME’s earliest models on hospitalizations were based on that CDC data and predicted that many states would quickly run out of hospital beds.

A subsequent model, released in early April, assumed about seven hospitalizations per death, reducing the predicted surge. Currently, Murray said, the ratio is about four hospital admissions per death.

“Initially what was happening and probably what we saw in the CDC data is doctors were admitting anybody they thought had COVID,” Murray said. “With time they started admitting only very sick people who needed oxygen or more aggressive care like mechanical ventilation.”

A model created by the Harvard Global Health Institute made a different assumption that also turned out to be too high. Data from Wuhan, China, suggested that about 20% of those known to be infected with COVID-19 were hospitalized. Harvard’s model, which ProPublica used to build a data visualization, assumed a hospitalization rate in the United States of 19% for those under 65 who were infected and 28.5% for those older than 65.

But in the U.S., that percentage proved much too high. Official hospitalization rates vary dramatically among states, from as low as 6% to more than 20%, according to data gathered from states by The COVID Tracking Project. (States with higher rates may not have an accurate tally of those infected because testing was so limited in the early weeks of the pandemic.) As testing increases and doctors learn how to treat coronavirus patients out of the hospital, the average hospitalization rate continues to drop.

New York state’s testing showed that by mid-April, approximately 20% of the adult population in New York City had antibodies to COVID-19. Given the number hospitalized in the city and adjusting for the time needed for the body to produce antibodies, this means that the city’s hospitalization rate was closer to 2%, said Dr. Nathaniel Hupert, an associate professor at Weill Cornell Medicine and co-director of the Cornell Institute for Disease and Disaster Preparedness.

Dr. Ashish Jha, director of the Harvard Global Health Institute, and his team also assumed that between 20% and 60% of the population would be infected with COVID-19 over six to 18 months. That was before stay-at-home orders took effect nationwide, which slowed the virus’s spread. Outside of New York City, a far lower percentage of the population has been infected. Granted, we’re not even six months into the pandemic.

A number of factors go into disease models, including the attack rate (the percentage of the entire population that eventually becomes infected), the symptomatic rate (how many people are going to show symptoms), the hospitalization rate for different age groups, the fraction of those hospitalized that will need intensive care and how much care they will need, as well as how the disease travels through the population over time (what is known as “the shape of the epidemic curve”), Hupert said.

Before mid-March, Hupert’s best estimate of the impact of COVID-19 in New York state was that it would lead to a peak hospital occupancy of between 13,800 to 61,000 patients in both regular medical wards and intensive care. He shared his work with state officials.

David Muhlestein, chief strategy and chief research officer at Leavitt Partners, a health care consulting firm, said one takeaway from COVID-19 is that models can’t try to predict too far into the future. His firm has created its own projection tool for hospital capacity that looks ahead three weeks, which Muhlestein said is most realistic given the available data.

“If we were held to our very initial projection of what was going to happen, everybody would be very wrong in every direction,” he said.

Hospitals Proved Surprisingly Adept at Adding Beds

When calculating whether hospitals would run out of beds, experts used as their baseline the number of beds in use in each hospital, region and state. That makes sense in normal times because hospitals have to meet stringent rules before they are able to add regular beds or intensive care units.

But in the early weeks of the pandemic, state health departments waived many rules and hospitals responded by increasing their capacity, sometimes dramatically. “Just because you only have six ICU beds doesn’t mean they will only have six ICU beds next week,” Muhlestein said. “They can really ramp that up. That’s one of the things we’re learning.”

Take Northwell Health, a chain of 17 acute-care hospitals in New York. Typically, the system has 4,000 beds, not including maternity beds, neonatal intensive care unit beds and psychiatric beds. The system grew to 6,000 beds within two weeks. At its peak, on April 7, the hospitals had about 5,500 patients, of which 3,425 had COVID-19.

The system erected tents, placed patients in lobbies and conference rooms, and its largest hospital, North Shore University Hospital, removed the chairs from its 300-seat auditorium and replaced them with a unit capable of treating about 50 patients. “We were pulling out all the stops at that point,” Senior Vice President Terence Lynam said. “It was unclear if the trend was going to go the other way. We did not end up needing them all.”

Northwell went from treating 49 COVID-19 inpatients on March 16 to 3,425 on April 7. “I don’t think anybody had a clear handle on what the ceiling was going to be,” Lynam said. As of Wednesday, the system was still caring for 367 COVID-19 patients in its hospitals.

As hospitals found ways to expand, government leaders worked with the Army Corps of Engineers to build dozens of field hospitals across the country, such as the one at the Javits Center. According to an analysis of federal spending by NPR, those efforts cost at least $660 million. “But nearly four months into the pandemic, most of these facilities haven’t treated a single patient,” NPR reported. As they began to come online, stay-at-home orders started producing results, with fewer positive cases and fewer hospitalizations.

Demand for Non-COVID-19 Care Plummeted More Than Expected

Hospitals across the country canceled elective surgeries, from hip replacements to kidney transplants. That greatly reduced the number of non-COVID-19 patients they had to treat. “We generated a lot more capacity by getting rid of elective procedures than any of us thought was possible,” Harvard’s Jha said.

Northwell canceled elective surgeries on March 16, and over the span of the next week and a half, its hospitals discharged several thousand patients in anticipation of the coming surge. “In retrospect, it was a wise move,” Lynam said. “It just ballooned after that. If we had not discharged those patients in time, there would have been a severe bottleneck.”

What’s more, experts say, it’s clear that some patients with true emergencies also stayed home. A recent report from the CDC said that emergency room visits dropped by 42% in the early weeks of the pandemic. In 2019, some 2.1 million people visited ERs each week from late March to late April. This year, that dropped to 1.2 million per week. That was especially true for children, women and people who live in the Northeast.

In New York City, emergency room visits for asthma practically ceased entirely at the peak, Cornell’s Hupert said. “You wouldn’t imagine that asthma would just disappear,” he said. “Why did it go away? … Nobody has seen anything like that.”

Undoubtedly some people experienced heart attacks and strokes and didn’t go to the hospital because they were fearful of getting COVID-19. “I didn’t expect that,” Jha said. A draft research paper available on a preprint server, before it is reviewed and published in an academic journal, found that heart disease deaths in Massachusetts were unchanged in the early weeks of the pandemic compared to the same period in 2019. What that may mean is that those people died at home.

The Coronavirus Attacked Every Region at a Different Pace

Some initial models forecast that COVID-19 would hit different regions in similar ways. That has not been the case. New York was hit hard early; California was not, at least initially.

In recent weeks, hospitals in Montgomery, Alabama, saw a lot of patients. Arizona’s health director has told hospitals in the state to “fully activate” their emergency plans in light of a spike in cases there. The Washington Post reported on Tuesday that hospitalizations in at least nine states have been rising since Memorial Day.

Dr. Mark Rupp, medical director of the Department of Infection Control and Epidemiology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha, said his region hasn’t seen a tidal wave like New York. “What we’ve seen is a rising tide, a steady increase in the number of cases.” Initially that was associated with outbreaks at specific locations like meatpacking and food processing plants and to some degree long-term care facilities.

But since then, “it has just plateaued,” he said. “That has me concerned. This is a time when I feel like we should be working as hard as we can to push these numbers as low as possible.”

Rupp’s hospital has been caring for 50 to 60 COVID-19 patients on any given day. The hospital has started to perform surgeries and procedures that had been on hold because “elective cases stay elective for only so long.”

The hospital’s general medical/surgical beds are 70% to 80% filled, and its ICU beds are 80% to 90% full. “We don’t have a big cushion.”

Even in New York City, the virus hit boroughs differently. Queens and the Bronx were hard hit; Manhattan, Brooklyn and Staten Island less so. “Maybe we can’t even model a city as big as New York,” Hupert said. “Each neighborhood seemed to have a different type of outbreak.”

That needs further study but could be attributable to both social and demographic conditions and the type of jobs residents of the neighborhoods had, among other factors.

What We Can Learn From Coronavirus “Round One”

While hospitals were able to add beds more quickly than experts realized they could, some other resources were harder to come by. Masks, gowns and other personal protective equipment were tough to get. So were ventilators. Anesthesia agents and dialysis medications were in short supply. And every additional bed meant the need for more doctors, nurses and respiratory therapists.

In early February, before any cases were discovered in New York, Northwell purchased $5 million in PPE, ventilators and lab supplies just in case, Lynam said. “It turned out to be a wise move,” he said. “What’s clear is that you can never have enough.”

Northwell has spent $42 million on PPE alone. “We were going through 10,000 N95 masks a day, just a crazy amount,” he said. “One of the lessons learned is you have to stockpile the PPE. There’s got to be a better procurement process in place.”

If there’s one thing the system could have done differently, Lynam said, it’s bringing in more temporary nurses earlier. Northwell brought in 500 nurses from staffing agencies. “They came in a week later than they should have.”

Dr. Robert Wachter, chair of the department of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, agreed. “I’ve helped run services in hospitals for 25 years,” he said. “I’ve probably given two minutes of thought to the notions of supply chains and PPE. You realize that is absolutely central to your preparedness. That’s a lesson.”

Experts and hospital leaders agree that everyone can do better if another wave hits. Here’s what that entails:

-

Having testing readily available, as it now is, to more quickly spot a resurgence of the virus.

-

Stocking up now on PPE and other supplies. “We definitely have to stockpile PPE by the fall,” Gershon of NYU said. “We have to. … [Hospitals and health departments] have to really get those contracts nailed down now. They should have been doing this, of course, all the time, but no one expected this kind of event.”

-

Being able to quickly move personnel and equipment from one hot spot to the next.

-

Planning for how to care for those with other medical ailments but who are scared of contracting COVID-19. “We have to have some sort of a mechanism by which we can offer people assurance that if they come in, they won’t get sick,” Jha said. “We can’t repeat in the fall what we just did in the spring. It’s terrible for hospitals. It’s terrible for patients.”

-

Providing mental health resources for front-line caregivers who have been deeply affected by their work. The intensity of the work, combined with watching patients suffer and die alone, was immensely taxing.

-

Coming up with ways to allow visitors in the hospital. Wachter said the visitor bans in place at many hospitals, though well intentioned, may have backfired. “When all hell was breaking loose and we were just doing the best we could in the face of a tsunami, it was reasonable to just keep everybody out,” he said. “We didn’t fully understand how important that was for patients, how much it might be contributing to some people not coming in for care when they really should have.”

Lynam of Northwell said he’s worried about what lies ahead. “You look back on the 1918 Spanish flu and the majority of victims from that died in the second wave. … We don’t know what’s coming on the second wave. There may be some folks who say you’re paranoid, but you’ve got to be prepared for the worst.”