https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jul/18/us-coronavirus-fall-second-wave-autumn

The breathing space afforded by lockdowns in the spring has been squandered, with new cases running at five times the rate of the whole of Europe. Things will only get worse, experts warn.

In early June, the United States awoke from a months-long nightmare.

Coronavirus had brutalized the north-east, with New York City alone recording more than 20,000 deaths, the bodies piling up in refrigerated trucks. Thousands sheltered at home. Rice, flour and toilet paper ran out. Millions of jobs disappeared.

But then the national curve flattened, governors declared success and patrons returned to restaurants, bars and beaches. “We are winning the fight against the invisible enemy,” vice-president Mike Pence wrote in a 16 June op-ed, titled, “There isn’t a coronavirus ‘second wave’.”

Except, in truth, the nightmare was not over – the country was not awake – and a new wave of cases was gathering with terrifying force.

As Pence was writing, the virus was spreading across the American south and interior, finding thousands of untouched communities and infecting millions of new bodies. Except for the precipitous drop in New York cases, the curve was not flat at all. It was surging, in line with epidemiological predictions.

Now, four months into the pandemic, with test results delayed, contact tracing scarce, protective equipment dwindling and emergency rooms once again filling, the United States finds itself in a fight for its life: swamped by partisanship, mistrustful of science, engulfed in mask wars and led by a president whose incompetence is rivaled only by his indifference to Americans’ suffering.

With flu season on the horizon and Donald Trump demanding that millions of students return to school in the fall – not to mention a presidential election quickly approaching – the country appears at risk of being torn apart.

“I feel like it’s March all over again,” said William Hanage, a professor of epidemiology at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health. “There is no way in which a large number of cases of disease, and indeed a large number of deaths, are going to be avoided.”

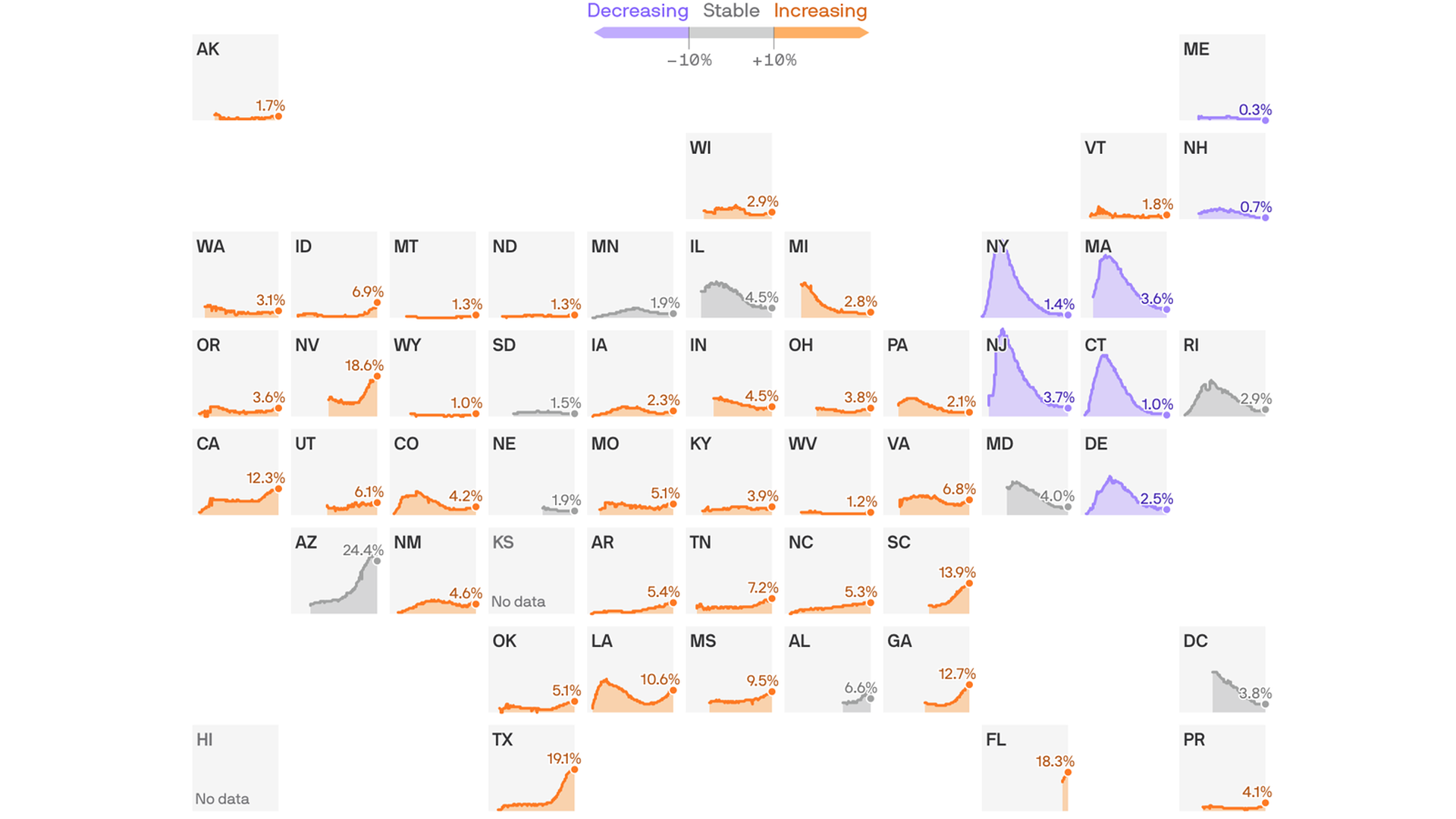

The problem facing the United States is plain. New cases nationally are up a remarkable 50% over the last two weeks and the daily death toll is up 42% over the same period. Cases are on the rise in 40 out of 50 states, Washington DC and Puerto Rico. Last week America recorded more than 75,000 new cases daily – five times the rate of all Europe.

“We are unfortunately seeing more higher daily case numbers than we’ve ever seen, even exceeding pre-lockdown times,” said Jennifer Nuzzo, an epidemiologist at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. “The number of new cases that occur each day in the US are greater than we’ve yet experienced. So this is obviously a very worrisome direction that we’re headed in.”

The mayor of Houston, Texas, proposed a “two-week shutdown” last week after cases in the state climbed by tens of thousands. The governor of California reclosed restaurants, churches and bars, while the governors of Louisiana, Alabama and Montana made mask-wearing in public compulsory.

“Today I am sounding the alarm,” Governor Kate Brown said. “We are at risk of Covid-19 getting out of control in Oregon.”

As dire as the current position seems, the months ahead look even worse. The country anticipates hundred of thousands of hospitalizations, if the annual averages hold, during the upcoming flu season. Those hospitalizations will further strain the capacity of overstretched clinics.

But a flu outbreak could also hamper the country’s ability to fight coronavirus in other ways. Because the two viruses have similar symptoms – fever, chills, diarrhea, fatigue – mistaken diagnoses could delay care for some patients until it’s too late, and make outbreaks harder to catch, one of the country’s top health officials has warned.

“I am worried,” Dr Robert Redfield, the director of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), said last week. “I do think the fall and the winter of 2020 and 2021 are probably going to be one of the most difficult times that we have experienced in American public health because of … the co-occurrence of Covid and influenza.”

Other factors will be in play. A precipitous reopening of schools in the fall, as demanded by Trump and the education secretary, Betsy DeVos, without safety measures recommended by the CDC, could create new superspreader events, with unknown consequences for children.

“We would expect that to be throwing fuel on the fire,” said Hanage of blanket school reopenings. “So it’s going to be bad over the next month or so. You can pretty much expect it to be getting worse in the fall.”

The list of aggravating circumstances goes on and on. A federal unemployment assistance program that gave each claimant an extra $600 a week is set to expire at the end of July. A new coronavirus relief package is being held up in Congress by Republicans’ accusations that states are wasting money, and their insistence that any new legislation include liability protections for businesses that reopen during the pandemic.

Cable broadcasts and social media have been filled, meanwhile, with video clips of furious confrontations on sidewalks, in stores and streets over wearing facial masks. In Michigan, a sheriff’s deputy shot dead a man who had stabbed another man for challenging him about not wearing a mask at a convenience store. In Georgia, the Republican governor sued the Democratic mayor of Atlanta for issuing a city-wide mask mandate.

The partisan divide on masks is slowly closing as the outbreaks intensify. The share of Republicans saying they wear masks whenever they leave home rose 10 points to 45% in the first two weeks of July, while 78% of Democrats reported doing so, according to an Axios-Ipsos poll.

Another divide has proven tragically resilient. As hotspots have shifted south, the virus continues to affect Black and Latinx communities disproportionately. Members of those communities are three times as likely to become infected and twice as likely to die from the virus as white people, according to data from early July.

The raging virus has prompted speculation in some corners that the only way out for the United States is through some kind of “herd immunity” achieved by simply giving up. But that grossly underestimates the human tragedy such a scenario would involve, epidemiologists say, in the form of tens of millions of new cases and unknown thousands of deaths.

“I think that every single serology study that’s been done to date suggests that the vast majority of Americans have not yet been exposed to this virus,” Nuzzo said. “So we’re still very much in the early stages.

“Which is good, that’s actually really good news. I don’t want to strive for herd immunity, because that means the vast majority of us will get sick and that will mean many, many more deaths. The point is to slow the spread as much as possible, protect ourselves as much as possible, until we have other tools.”

But the ability of the US to take that basic step – to slow the spread, as dozens of other countries have done – is in perilous doubt. After half a year, the Trump administration has made no effort to establish a national protocol for testing, contact tracing and supported isolation – the same proven three-pronged strategy by which other countries control their outbreaks.

Critics say that instead, Trump has dithered and denied as the national death toll climbed to almost 140,000. The Democratic presidential candidate, Joe Biden, who is hoping to unseat Trump in November, blasted the president for refusing until recently to wear a mask in public.

“He wasted four months that Americans have been making sacrifices by stoking divisions and actively discouraging people from taking a very basic step to protect each other,” Biden said in a statement last weekend.

Meanwhile the White House has attacked Dr Anthony Fauci, the country’s foremost expert on infectious diseases whose refusal to lie to the public has enraged Trump, by publishing an op-ed signed by one of the president’s top aides titled “Anthony Fauci has been wrong about everything I have interacted with him on” and by releasing a file of opposition research to the Washington Post.

Trump claimed the number of cases was a function of unusually robust testing, though experts said that positivity rates of 20% in multiple states suggested that the United States is testing too little – and that in any case closing one’s eyes to the problem by testing less would not make it go away.

“We’ve done 45 million tests,” Trump said this week, padding the figure only slightly. “If we did half that number, you’d have half the cases, probably around that number. If we did another half of that, you’d have half the numbers. Everyone would be saying we’re doing well on cases.”

Such statements by Trump have encouraged unfavorable comparisons of the US pandemic response with those in countries such as Italy, which recorded just 169 new cases on Monday after a horrific spring, and South Korea, which has kept cases in the low double-digits since April.

But the United States could also look to many African countries for lessons in pandemic response, said Amanda McClelland, who runs a global epidemic prevention program at Resolve to Save Lives.

“We’ve seen some good success in countries like Ghana, who have really focused on contact tracing, and being able to follow up superspreading events,” said McClelland. “We see Ethiopia: they kept their borders open for a lot longer than other countries, but they have really aggressive testing and active case-finding to make sure that they’re not missing cases.

“I think what we’ve seen is that you need not just a strong health system but strong leadership and governance to be able to manage the outbreak, and we’ve seen countries that have all three do well.”

But in America, the large laboratories that process Covid-19 tests are unable to keep up with demand. Quest Diagnostics announced on Tuesday that the turnaround time for most non-emergency test results was at least seven days.

“We want patients and healthcare providers to know that we will not be in a position to reduce our turnaround times as long as cases of Covid-19 continue to increase dramatically,” the lab said.

“You can’t have unlimited lab capacity, and what we’ve done is allow, to some extent, cases to go beyond our capacity,” said McClelland. “We’re never going to be able to treat and track and trace uncontrolled transmission. This outbreak is just too infectious.”

Public health experts emphasize that the United States does not have to accept as its fate a cascade of tens of millions of new cases, and tens of thousands of deaths, in the months ahead. Focused leadership and individual resolve could yet help the country follow in the footsteps of other nations that have successfully faced serious outbreaks – and brought them under control.

But it is clear that the most vulnerable Americans, including the elderly and those with pre-existing conditions, face grave danger. Republicans have argued in recent weeks that while cases in the US have soared, death rates are not climbing so quickly, because the new cases are disproportionately affecting younger adults.

That is a false reassurance, health experts say, because deaths are a lagging indicator – cases necessarily rise before deaths do – and because large outbreaks among any demographic group speeds the virus’s ability to get inside nursing homes, care facilities and other places where residents are most vulnerable.

“If we don’t do anything to stop the virus, it’s going to be very difficult to prevent it from getting to people who will die,” said Nuzzo.

There is a question of whether the United States, for all its wealth and expertise – and its self-regard as an exceptional actor on the world stage – can summon the will to keep up the fight. People are tired of fighting the virus, and of fighting each other.

“I think unfortunately people are emotionally exhausted from having to think about and worry about this virus,” said Nuzzo. “They feel like they’ve already sacrificed a lot. So the worry that I have is, what willingness is there left, to do what it takes?”

It is as if the country is “treading water in the middle of the ocean”, Hanage said.

“People tend to be shuffling very quickly between denial and fatalism,” he said. “That’s really not helpful. There are a number of things that can be done.

“What I would hope is that this marks a point when the United States finally wakes up and realizes that this is a pandemic and starts taking it seriously.

“Folks tend to look at what has happened elsewhere and then they make up some kind of magical reason why it’s not going to happen to them.

“People keep making these excuses, and the virus doesn’t care about the excuses. The virus just keeps going. If you give it the opportunity, it will take it.”