https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200522.474405/full/?utm_source=Newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_content=COVID-19%3A+Reducing+Deaths+In+Nursing+Homes%2C+Effective+Multilateralism%3B+Surprise+Out-Of-Network+Bills+For+Ambulance+Transportation+And+Ambulatory+Surgery+Centers&utm_campaign=HAT+5-27-20

Nursing homes are a hidden and frequently forgotten part of our health care system. They are now under attack by the COVID-19 pandemic: residents are dying, families are disconnected from their loved ones, and staff are sick and overwhelmed by work and the grief of losing so many patients in such a short time. Our state, Massachusetts, is one of the hardest-hit by COVID-19, with over 3,600 deaths and counting in nursing homes, or almost 10 percent of the nursing home population. Over 60 percent of all COVID-19-related deaths in Massachusetts are in nursing homes, one of six states where nursing home residents comprise over 50 percent of COVID-19-related deaths. The COVID-19 pandemic is exposing years of neglect and chronic underfunding of nursing homes.

Over 85 percent of the almost 400 nursing homes in Massachusetts currently report two or more cases of COVID-19 among residents or staff. Emerging data make it abundantly clear that the nursing home environment is highly conducive to the rapid spread of COVID-19, and nursing home residents are among the most susceptible to severe illness and death. Urgent and decisive action is required to reduce mortality among frail and vulnerable seniors in nursing homes.

The New England Geriatrics Network (NEGN) is a group of geriatricians, geriatric psychiatrists, nurse practitioners, and others interested in improving care of older adults, that recently convened a Nursing Home Work Group of members interested in improving nursing home care. We write to share our collective experiences and to reflect on some innovative and promising initiatives adopted in our state.

Success in reducing COVID-19-related morbidity and mortality in the nursing home setting requires urgent action in three areas: 1) enhancing infection control with an individualized plan for each nursing home that incorporates both regulatory guidance and current literature and is feasible to implement; 2) ensuring necessary resources to implement infection control plans, especially adequate staff, training, personal protective equipment (PPE), COVID-19 testing, creation of units for COVID-19 positive patients, and access to onsite ancillary services (labs, imaging, intravenous (IV) management); 3) mirroring the federal Coronavirus Commission for Safety and Quality in Nursing Homes by establishing state-level task forces focused on improving communication and collaboration between nursing homes and families, health care providers (hospitals, health systems, home health agencies, physician organizations), and government agencies.

Although the federal government has offered guidance on infection control in nursing homes, most efforts to manage the pandemic are initiated and managed at the state level. As a result, there is significant variability in the response. For example, until the federal government recently mandated it, fewer than half of the states reported infection rates and deaths in nursing homes. Massachusetts implemented several key initiatives that may serve as a model for how to limit COVID-19 epidemic in nursing homes.

Recommendation #1: Operationalizing Effective Infection Control

The only way to reduce COVID-19 deaths is to universally implement effective infection control programs in every nursing home. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), state agencies like the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, and medical specialty societies have issued checklists and guidance for managing COVID-19 infections in nursing homes. The core challenge is the diversity of the nursing homes, each varying structurally in layout and room design, financially in resources and reserves, and organizationally in staffing and medical leadership. Nationally, 39 percent of nursing homes had deficiencies related to infection control in 2017, including 30 percent of Massachusetts nursing homes. Each nursing home must create and implement a COVID-19 control plan, review it regularly with public health officials, and allow site visits to validate performance. A truly collaborative effort will empower and support nursing homes to make required changes, maintain transparency, uphold accountability, and save lives.

Our colleagues working in Massachusetts nursing homes continue to directly observe ongoing issues with infection control, despite the state’s best efforts to address the pandemic. In late April, a colleague rounding at a nursing home with known COVID-19 cases found COVID-19-positive, test pending, and COVID-19-free residents sitting together in a communal area. Nurses were wearing varying levels of PPE, some in gowns and masks, and only some with face shields.

Massachusetts recently enhanced its plan to manage COVID-19 in nursing homes by allocating up to $130 million in additional funding to support infection control, staffing, and PPE. Part of the plan is a 28-point audit tool to evaluate the strength of each nursing home’s plan, which will be assessed through site visits by state inspectors to every nursing home in the state either every two or four weeks (depending on initial audit results) through the end of June. Nursing homes can qualify for up to a 50 percent increase over their baseline Medicaid (MassHealth) reimbursement by demonstrating adherence to an effective infection control plan. Facilities failing to implement effective plans can face serious penalties starting with reduced bonus funding and extending to receivership, termination from the state Medicaid program and even forced closure.

In addition to a clear and transparent approach to audits, the state is providing access to infection control expertise to enhance the ability of nursing homes to execute effective infection control plans. A statewide infection control command center is being led by the nursing home trade organization Massachusetts Senior Care Association (MSCA), along with a senior care and housing organization, Hebrew Senior Life, and others.

Comprehensive infection control plans may require dedicated units for COVID-19-infected patients, important for preventing spread of the infection within nursing homes and for treating COVID-19-positive patients needing inpatient nursing and rehabilitation. Massachusetts made this a focus of the first phase of its approach to managing COVID-19 in nursing homes. As of May 1, 2020, six nursing homes have been fully converted to COVID-only facilities, and more than 80 nursing homes have dedicated in-house COVID units. The state accelerated the creation of these facilities with increased Medicaid payment rates for the care of patients with COVID-19. This has helped offset revenue loss related to decreased post-acute care admissions due to a decrease in elective procedures.

Recommendation #2: Nursing Homes Must Have Adequate Resources For Patient Care Including Staffing, PPE, Testing, And Onsite Ancillary Services

The lack of infection control resources reflects longstanding gaps in the nursing home setting which have been greatly exacerbated by the current pandemic. The state is providing additional Medicaid payments to nursing homes, as mentioned above. These resources are needed to improve care and infection control.

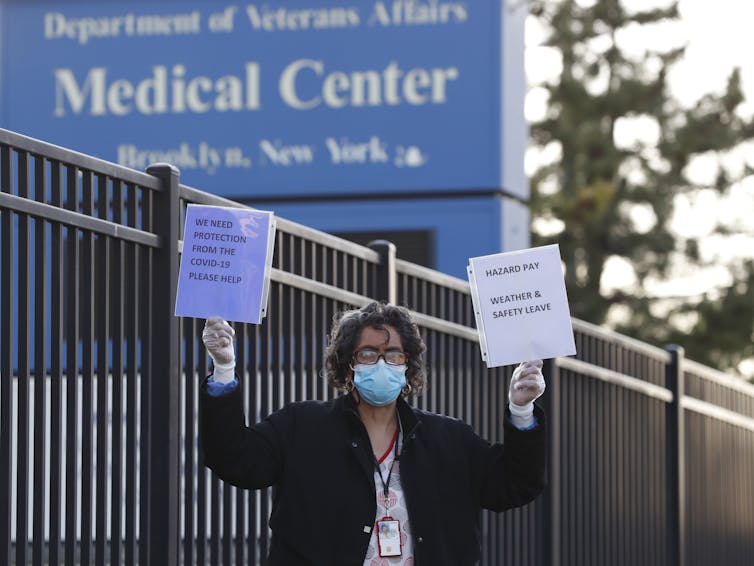

Staffing

In mid-April, as the surge in COVID-19 cases accelerated in Massachusetts, 40 percent of nursing home positions were vacant in the state As the pandemic spread, many staff became unavailable due to infection, increased risk related to underlying comorbidities, or family responsibilities. Many nursing home staff work on a per diem basis, and often lack paid sick leave. Until recently, transportation and paid housing solutions put in place for hospital staff had not been extended to them.

The staffing shortage threatens the health of all residents on short-staffed units and reveals how human contact is fundamental to good nursing home care. A member of our group recently visited a nursing home where staffing on a 30-resident unit was reduced to one nurse and one nurse’s aide. Isolation is a cornerstone of fighting COVID-19, but with family and volunteers not permitted in nursing homes, he reported seeing increased dehydration, falls, and poor hygiene as staff struggled to hand-feed residents and provide personal care. In addition, family members may wait days to hear back about their loved one from overwhelmed nursing home staff. This lack of communication is a huge barrier to high quality care, especially for patients needing frequent symptom management, such as those in hospice care.

Massachusetts is taking several actions to alleviate staffing shortages. The state offered a $1,000 bonus for new nursing home staff, and an online portal was created to match nursing homes with job seekers and volunteers. The state is making available rapid response teams including nurses, emergency medical technicians (EMTs), and others that can be temporarily deployed for a few days to assist challenged nursing homes. National Guard units are available for non-clinical support, as well as staff from temporary staffing agencies contracted by the state. Private sector efforts include a collaboration between Massachusetts Senior Care Association, the MIT COVID-19 Policy Alliance, and Monster.com to offer free staffing listings on Monster’s recruiting website.

Personal Protective Equipment

As with all other health care settings, PPE shortages are an ongoing challenge, and states must do more to help. In Massachusetts, as of May 19, 2020, the state has distributed almost 350,000 N95 masks, over 780,000 masks, and 708,000 pairs of gloves to nursing homes. However, this is not enough to provide for all of the needs of the nearly 400 nursing homes in the state, which must still rely on their own supply chains, including new purchasing collaboratives, to help facilities gain PPE access. Providing PPE to family members and volunteers could help mitigate some of the impact of extreme staffing shortages.

Testing For COVID-19

Access to routine testing can improve infection control and identify patients at risk of decline. Testing should not be limited to only those with symptoms. In early April, a nursing home in Wilmington, MA underwent facility-wide screening. Over 50 percent of residents without symptoms tested positive for COVID-19, and within two weeks, 25 residents had died. Universal testing of residents and staff should be performed as quickly as possible, and routine testing must be available to evaluate symptomatic nursing home residents. The state of Massachusetts now requires every nursing home to test all residents and staff as a prerequisite to receiving any supplemental COVID-19 funding. If the nursing home cannot arrange testing, the state will continue to supply National Guard mobile testing teams and dispense testing kits directly to nursing homes. For nursing homes where testing may not be readily available, or if there are already significant numbers of COVID-19 infections, it should be presumed that all residents and staff are infected, and PPE and other universal infection control measures should be implemented.

Ancillary Services

One overlooked but essential resource is access to ancillary services. Most nursing homes rely on external companies to provide onsite services, including laboratory tests (e.g. blood tests, urinalysis), to start IVs and provide portable imaging (X-Ray, ultrasound), and to stock medications. Many of these companies also face challenges with staff and PPE and have decreased services from daily visits to once or twice a week. As a result, families who want their loved one diagnosed and treated in the nursing home (e.g. chest x-ray, labs for possible pneumonia, followed by IV insertion for antibiotics), or who need urgent assessments, COVID-19 related or not, must decide whether to transfer their family member to the emergency department. One solution is redeploying EMTs, now freed up from transport for elective procedures, to draw labs and start IVs in nursing homes to keep patients where they feel safe and comfortable, and to avoid further stress on over-burdened emergency departments.

Recommendation #3: Establishing COVID-19 Control Task Forces

COVID-19 has forced our society into isolation, but communication and collaboration are essential for successfully fighting pandemics. We strongly recommend each state create a task force for COVID-19 pandemic control in nursing homes for a minimum of two years, to bring together relevant governmental agencies (Public Health, Elder Affairs or Aging agency, Emergency Management, Medicaid, and others) and other key stakeholders, which include nursing home clinicians, the nursing home industry, ancillary services companies, hospitals, physician groups, and nursing home residents and family members. Local and regional task forces should collaborate to support links between nursing homes and local health care systems and ensure that nursing homes have effective communications with family members and clinicians providing care. Collaboration with state governments and nursing home leadership in other states is also essential, as many staff, clinicians, and family members travel across state lines.

Task Forces must initially focus on ensuring effective infection control and making resources available to reduce the morbidity and mortality of COVID-19 on nursing home residents and those needing post-acute care. They also should anticipate and plan for the inevitable changes and continued need for nursing home care in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In Summary

Nursing homes should receive necessary support as an integral and most vulnerable part of the continuum of care. The population is aging, and the need for high quality long-term care, especially for those who lack family or financial resources, is growing rapidly. Now is the time to ensure the safety and continued viability of this vital health care setting.

Authors’ Note: This call to action was written by the co-authors above on behalf of The New England Geriatrics Network (NEGN) Nursing Home Work Group.