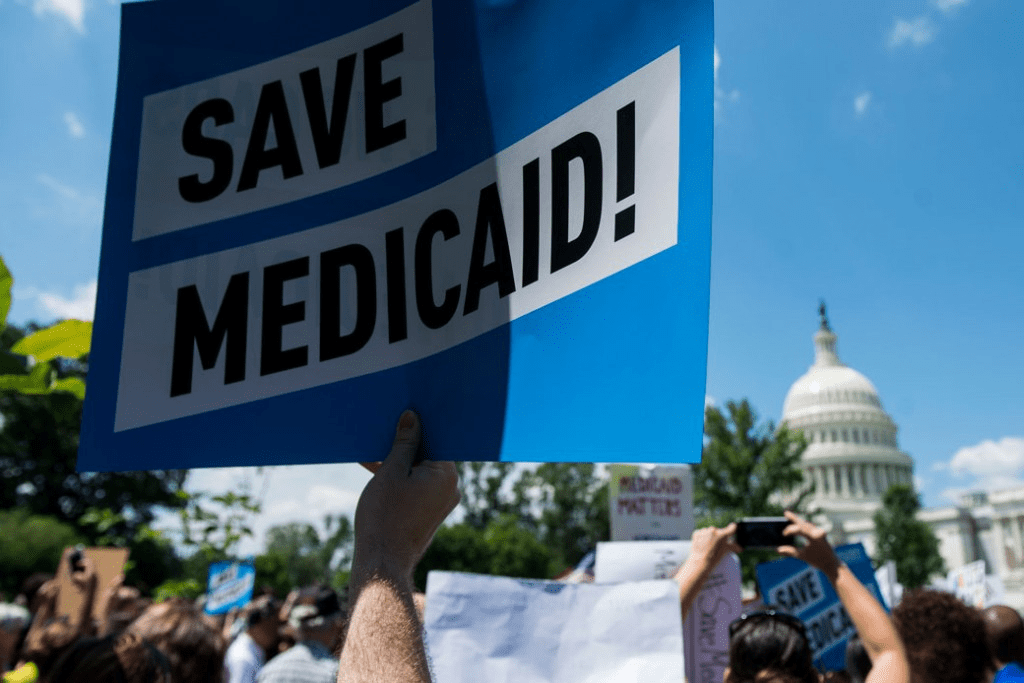

Medicaid serves as a vital source of health insurance coverage for Americans living in rural areas, including children, parents, seniors, individuals with disabilities, and pregnant women. Congressional lawmakers are currently considering more than $800 billion in cuts to the Medicaid program, which would reduce Medicaid funding and terminate coverage for vulnerable Americans.

The proposed changes would also result in a significant reduction in Medicaid reimbursement that could result in rural hospital closures.

The National Rural Health Association recently partnered with experts from Manatt Health to shed light on the potential impacts of those cuts on rural residents and the hospitals that care for them over the next decade.

The report, Estimated Impact on Medicaid Enrollment and Hospital Expenditures in Rural Communities, provides insight into the impact on rural America at a critical moment in the Congressional debate over the future of the reconciliation package.

NRHA held a press conference on June 24 that can be accessed with passcode MBTZf4$H. NRHA chief policy officer Carrie Cochran-McClain discussed the findings with Manatt Health partner and former deputy administrator at CMS Cindy Mann and the real world implications of the details of this report with three NRHA member hospital and health system leaders

Report findings provide insight into the impact on rural America at a critical moment in the Congressional debate over the future of the reconciliation package.

The report shows the significant impact from coverage losses that rural communities will face given:

- Medicaid plays an outsized role in rural America, covering a larger share of children and adults in rural communities than in urban ones.

- Nearly half of all children and one in five adults in small towns and rural areas rely on Medicaid or CHIP for their health insurance.

- Medicaid covers nearly one-quarter of women of childbearing age and finances half of all births in these communities.

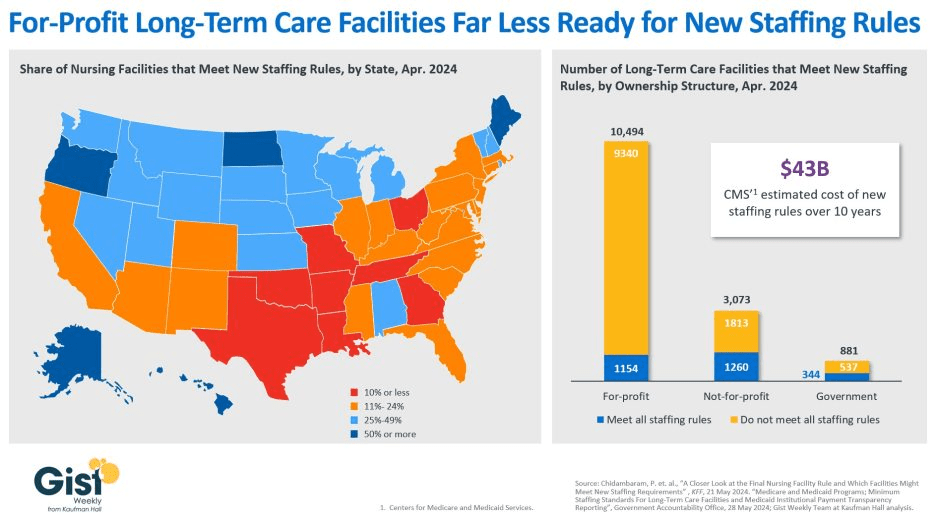

According to Manatt’s estimates, rural hospitals will lose 21 cents out of every dollar they receive in Medicaid funding due to the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. Total cuts in Medicaid reimbursement for rural hospitals—including both federal and state funds—over the ten-year period outlined in the bill would reach almost $70 billion for hospitals in rural areas.

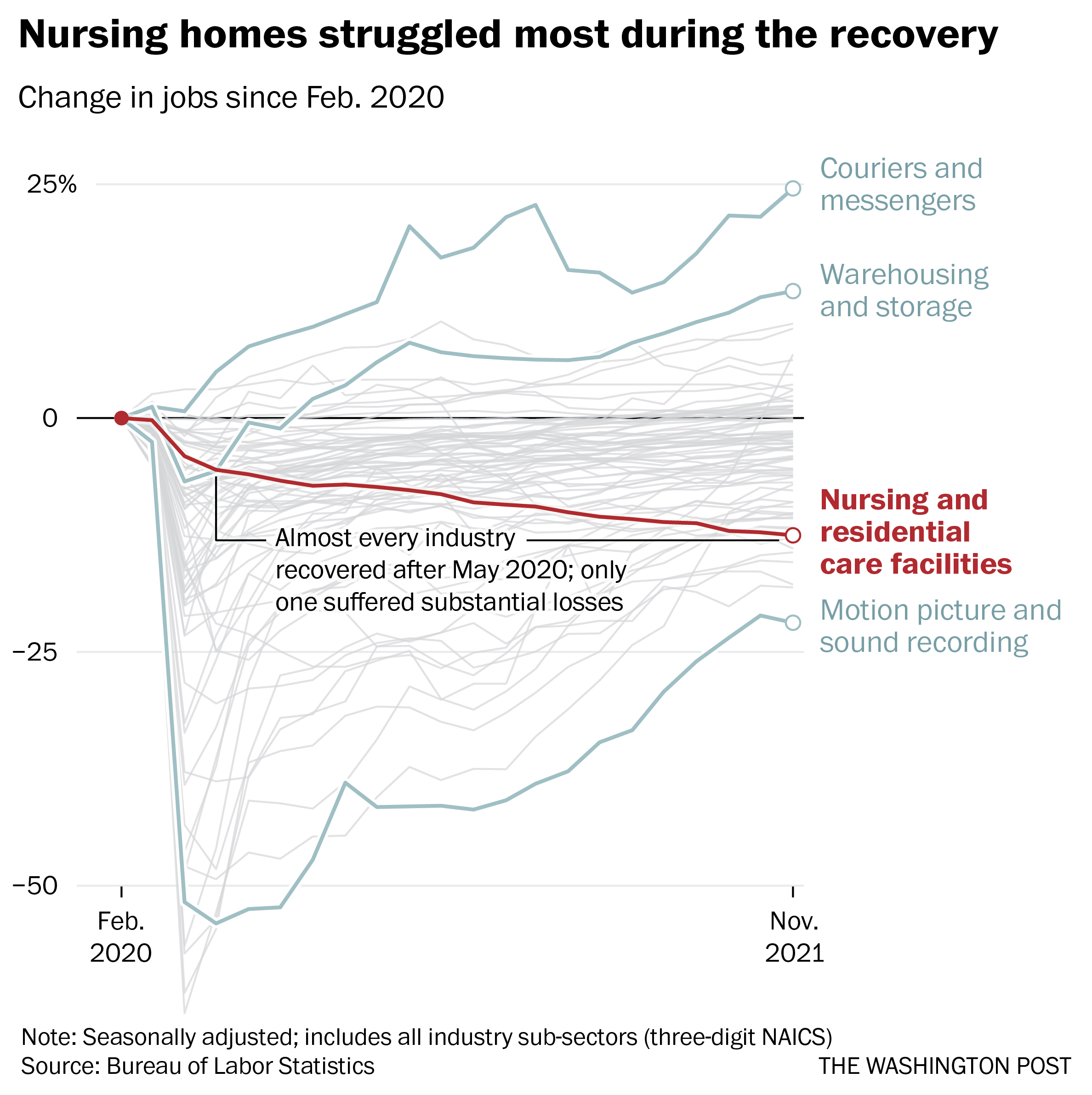

Reductions in Medicaid funding of this magnitude would likely accelerate rural hospital closures and reduce access to care for rural residents, exacerbating economic hardship in communities where hospitals are major employers.

As a key insurer in rural communities, Medicaid provides a financial lifeline for rural health care providers — including hospitals, rural health clinics, community health centers, and nursing homes—that are already facing significant financial distress. These cuts may lead to more hospitals and other rural facility closures, and for those rural hospitals that remain open, lead to the elimination or curtailment of critical services, such as obstetrics.

“Medicaid is a substantial source of federal funds in rural communities across the country. The proposed changes to Medicaid will result in significant coverage losses, reduce access to care for rural patients, and threaten the viability of rural facilities,” said Alan Morgan, CEO of the National Rural Health Association.

“It’s very clear that Medicaid cuts will result in rural hospital closures resulting in loss of access to care for those living in rural America.”

A media briefing will be held on Tuesday, June 24, from noon to 1:00 PM EST to provide more information about the analysis. This event will feature representatives from NRHA, Manatt Health, and rural hospital leaders across the country. Questions may be submitted in advance, as well as during the press conference. To register for and join the media briefing, click on the Zoom link here.

Please reach out to NRHA’s Advocacy Team with any questions.

About the National Rural Health Association

NRHA is a non-profit membership organization that provides leadership on rural health issues with tens of thousands of members nationwide. Our membership includes nearly every component of rural America’s health care, including rural community hospitals, critical access hospitals, doctors, nurses, and patients. We work to improve rural America’s health needs through government advocacy, communications, education, and research. Learn more about the association at RuralHealth.US.

About Manatt Health

Manatt Health is a leading professional services firm specializing in health policy, health care transformation, and Medicaid redesign. Their modeling draws upon publicly available state data including Medicaid financial management report data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, enrollment and expenditure data from the Medicaid Budget and Expenditure System, and data from the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. The Manatt Health Model is tailored specifically to rural health and has been reviewed in consultation with states and other key stakeholders.