While healthcare workers battle burnout, hospitals have been ramping up wages and other benefits to recruit and retain workers. It has created a culture of competition among health systems as well as travel agencies that offer considerably higher pay.

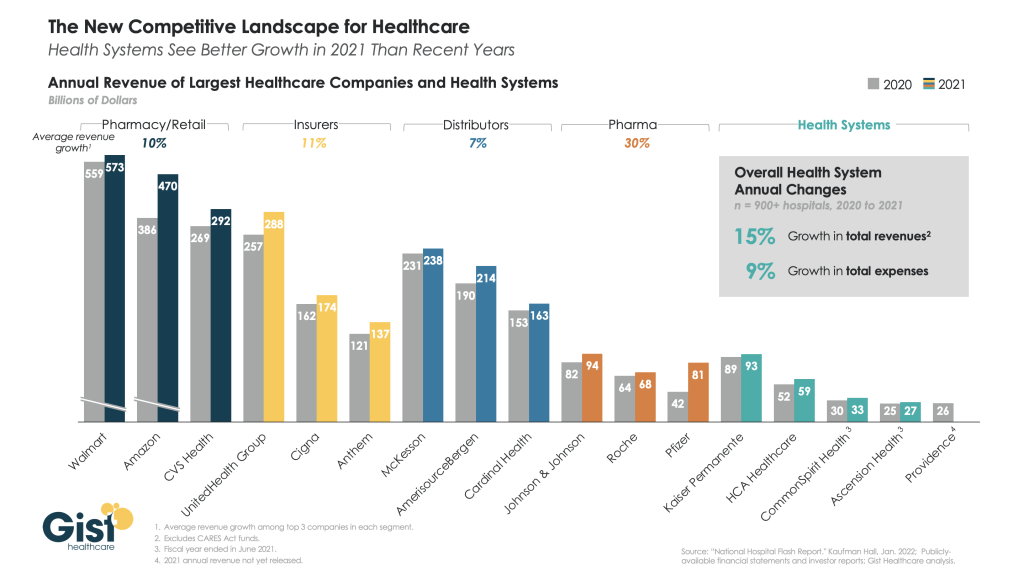

But other healthcare organizations are not hospitals’ only competitors. Some hospitals, particularly those in rural areas, are struggling to match rising employee pay among nonindustry employers such as Target and Walmart.

“We monitor and we’ve been looking and we ask around in the community and we can ask who’s paying what,” Troy Bruntz, CEO of Community Hospital in McCook, Neb., told Becker’s. “So we know where Walmart is on different things, and we’re OK. But if Walmart tried to match what Target’s doing, that would not be good.”

At Target, the hourly starting wage now ranges from $15-$24. The organization is making a $300 million investment total to boost wages and benefits, including health plans. Starting pay is dependent on the job, the market and local wage data, according to NPR.

Walmart raised the hourly wages for 565,000 workers in 2021 by at least $1 an hour, The New York Times reported. The company’s average hourly wage is $16.40, with the lowest being $12 and the highest being $17.

Meanwhile, Costco raised its minimum wage to $17 an hour, according to NPR. The federal minimum wage is $7.25.

Estimated employment for healthcare practitioners and technical occupations is 8.8 million, according to the latest data released March 31 by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. This includes nurse practitioners, physicians, registered nurses, physician assistants and respiratory therapists, among others.

In sales and related occupations, estimated employment is 13.3 million, according to the bureau. This includes retail salespersons, cashiers and first-line supervisors of retail salespersons, among others.

While retail companies up their wages, at least one hospital CEO is monitoring the issue.

Healthcare leaders weigh their options

Mr. Bruntz said rising wages among retailers is an issue his organization monitors. Although Target does not have a store in McCook, there is a Walmart, where pay is increasing.

“I was quoted a few months ago saying Walmart was approaching $15 an hour, and we can handle that,” Mr. Bruntz said. “But when it gets to $20 or $25, it’s going to be an issue.”

He also said he cannot solely increase the wages of the people making less than $15 or less than $25 because he has to be fair in terms of wages for different types of roles.

Specifically, he said he is concerned about what matching rising wages at retailers would mean for labor expenses, which make up about half of the hospital’s cost structure.

“I double that half, that’s 25 percent more expenses instantly,” Mr. Bruntz said. “And how is that going to ratchet to a bottom line anything less than a massive negative number? So it’s a huge problem.”

Clinical positions are not the only ones hospitals and health systems are struggling to fill; they are encountering similar difficulties with technicians and food service workers. Regarding these roles, competition from industries outside healthcare is particularly challenging.

This is an issue Patrice Weiss, MD, executive vice president and chief medical officer of Roanoke, Va.-based Carilion Clinic, addressed during a Becker’s panel discussion April 4. The organization saw workforce issues not just in its clinical staff, but among environmental services staff.

“When you look at what … even fast food restaurants were offering to pay per hour, well gosh, those hours are a whole lot better,” she said during the panel discussion. “There’s no exposure. You’re not walking into a building where there’s an infectious disease or patients with pandemics are being admitted.”

Amid workforce challenges, Community Hospital is elevating its recruitment and retention efforts.

Mr. Bruntz touted the hospital as a hard place to leave because of the culture while acknowledging the monetary efforts his organization is making to keep staff.

He said the hospital has a retention program where full-time employees get a bonus amount if they are at the employer on Dec. 31 and have been there at least since April 15. Part-time workers are also eligible for a bonus, though a lesser amount.

“It also encourages staff [who work on an as-needed basis] to go part-time or full-time, and [those who are] part-time to go full-time,” Mr. Bruntz said. “That’s another thing we’re doing is higher amounts for higher status to encourage that trend.”

Additionally, Community Hospital, which has 330 employees, offers a referral bonus to staff to encourage people they know to come work with them.

“We want staff to bring people they like. [We are] encouraging staff to be their own ambassadors for filling positions,” Mr. Bruntz said.

He said the hospital also will offer employees a sizable market wage adjustment not because of competition from Walmart but because of inflation.

Graham County Hospital in Hill City, Kan., is also affected by the tight labor market, although it has not experienced much competition with retail companies, CEO Melissa Atkins told Becker’s. However, the hospital is struggling with competition from other healthcare organizations, particularly when it comes to patient care departments and nursing. While many hospitals have struggled to retain employees from travel agencies, Graham County Hospital has mostly been able to avoid it.

“As the demand increases, so does the wage,” Ms. Atkins said. “In addition to other hospitals offering sign-on bonuses and increased wages, nurse agency companies are offering higher wages for traveling nurse aides and nurses. We are extremely fortunate in that we have not had to use agency nurses. Our current staff has stepped up and filled in the shortages [with additional incentive pay].”

To combat this trend, the hospital has increased hourly wages and shift differentials, as many healthcare organizations have done. It has also provided bonuses using COVID-19 relief funds.

Overall, Mr. Bruntz said he prefers “not to get into an arms race with wages” among nonindustry competitors.

“It’s not going to end well for anybody. We prefer not to use that,” he said. “At the same time, we’re trying to do as much as possible without being in a full arms race. But if Walmart started paying $25 for a door greeter and cashier, we would have to reassess.”