https://www.healthcaredive.com/news/6-months-in-new-normal-hospitals-covid/581524/

Experts say a sustained state of emergency is likely until there is a cure or vaccine for COVID-19.

The first U.S. hospital to knowingly treat a COVID-19 patient was Providence Regional Medical Center in Everett, Washington, on Jan. 20. Since then, every aspect of healthcare has been upended, and it’s becoming increasingly clear all parts of society will have to adapt to a new baseline for the foreseeable future.

For hospitals and doctors’ offices, that means building on a major shift to telemedicine, new workflows to allow for more infection control and revamping the supply chain for pharmaceuticals, personal protective equipment and other supplies. That’s on top of ongoing challenges of burned out workers and staff shortages further exacerbated by the pandemic.

Looking out even further, the industry will have to figure out how to treat potential chronic conditions in COVID-19 survivors and, until an effective vaccine is developed, how to manage new outbreaks of the disease.

Experts say U.S. hospitals are generally in a much better position for dealing with COVID-19 now than they were in March, and providers are learning more every week about the best treatments and care practices.

A June survey of healthcare executives conducted by consultancy firm Advis found that 65% of respondents said the industry is prepared for a fall or winter surge, about the inverse of what an earlier survey with that question showed.

“We’ve evolved. We’re in a much better state now than we were in the beginning of the pandemic,” Michael Calderwood, associate chief quality officer at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, told Healthcare Dive. “There’s been a lot of learning.”

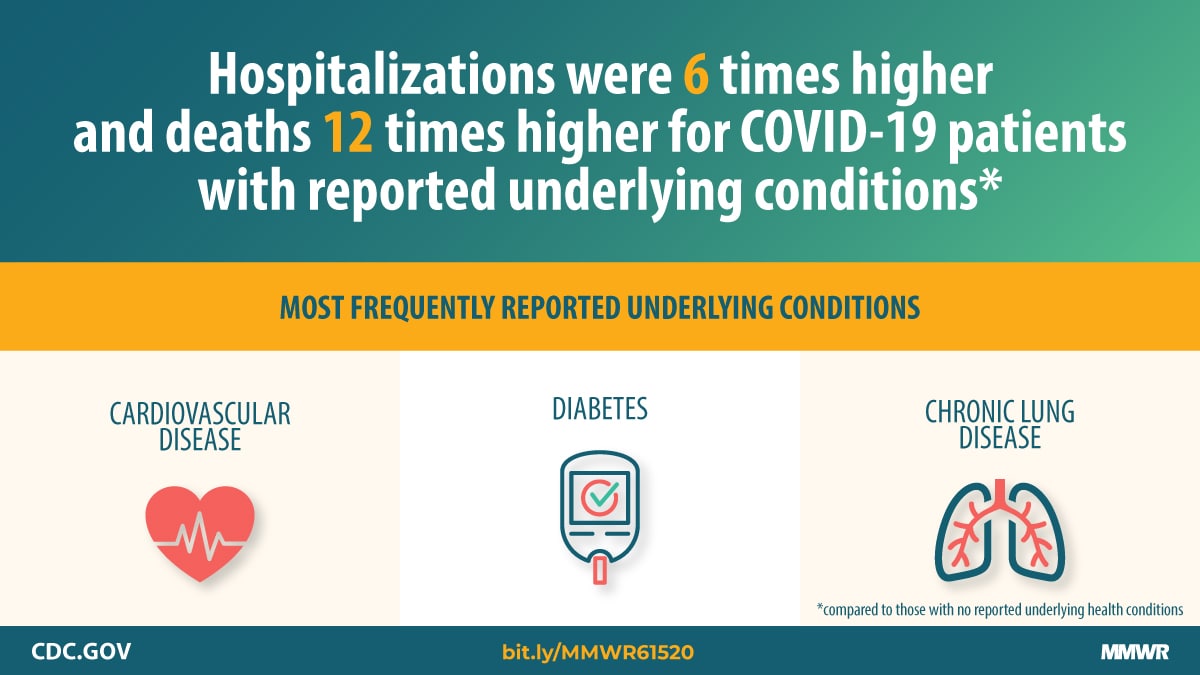

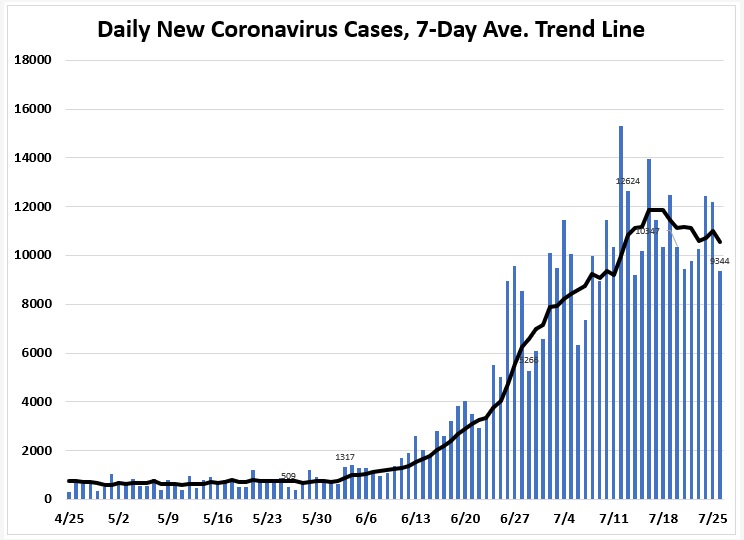

But the number of positively identified cases has now topped 4 million, and little political will exists to reinstitute widespread shutdowns even in areas where surges have filled ICUs to capacity. No treatment or vaccine for the disease exists or appears imminent. Testing and contract tracing efforts are too few and remain scattered and uncoordinated.

Whether there is a clear nationwide second wave or smaller surges in various parts of the country at different times, hospitals will need to remain in an effective state of emergency that requires constant vigilance until there is a cure or vaccine.

“Until we’re armed with that, we’re always going to have to be working like this. I don’t see any other way,” Diane Alonso, director of Intermountain Healthcare’s abdominal transplant program, told Healthcare Dive.

The fall will bring additional challenges. Flu season usually begins to ramp up in October, and if the strains in wide circulation this year are severe, that will further stress the health system. While some schools have announced they will be virtual-only for the rest of 2020, others are committed to in-person classes. That could mean increased community spread, especially in college towns. Colder weather that forces people indoors — where the novel coronavirus is far more likely to spread — will also be a complicating factor.

So far, hospitals have been reluctant to once again halt elective procedures, though some have had to, arguing that the care is still necessary and can be done safely when the proper protections are in place. But that doesn’t mean volume will rebound to pre-pandemic levels.

“While we think demand will come back, we’ve seen some flattening on demand in certain aspects that may be the new indicator of the new norm in terms of how people seek care,” Dion Sheidy, a partner and healthcare advisory leader at advisory firm KPMG, told Healthcare Dive.

Accelerating trends to provide care outside hospitals

When the number of COVID-19 cases first surged in the U.S. and stay-at-home orders were implemented nationwide, telehealth became a necessary way for urgent care to continue.

Virtual visits skyrocketed in March and April as CMS and private payers relaxed regulations and expanded coverage. Some of that will be rolled back, but much may persist as patients and providers grow more used to using telehealth and platforms become smoother.

Virtual care can’t replace in-person care, of course, and some patients and doctors will prefer face-to-face visits. The middle- to long-term result is likely to be that telehealth thrives for some specialties like psychiatry, but drops substantially from the highest levels during shutdowns throughout the country.

Other care settings outside of the hospital may see upticks as well, including at-home and retail-based primary and urgent care.

Renee Dua, the CMO of home healthcare and telemedicine startup Heal, said the company has seen virtual visits increase eight fold since the pandemic began in the U.S. and a 33% increase in home visits as people seek to continue care while reducing their risk of exposure to the coronavirus.

“The idea that you do not use an office building to get care — that’s why we started Heal — we bet on the fact that the best doctors come to you,” Dua told Healthcare Dive.

And care does need to continue, particularly vital services like vaccinations and pediatric checkups.

“You cannot ignore preventive screenings and primary care because you can get sick with cancer or with infectious diseases that are treatable and preventable,” Dua said.

Movements toward non-traditional settings existed before anyone had heard of COVID-19, but the realities of the pandemic have shifted resources and spurred investment that will have lasting effects, Ross Nelson, healthcare strategy leader at KPMG, told Healthcare Dive.

“What we’re going to see is there going to be an acceleration of the underlying trends toward home and away from the hospital,” he said.

Some of this was already underway. Multiple large health systems have established programs to provide hospital-level care at home and major employers have inked contracts to have primary care delivered to employees at on-site clinics.

PPE, staff shortages lingering

A key problem for hospitals in the first COVID-19 hotspots, such as Washington state and New York City, was a lack of necessary personal protective equipment, including N95 masks, gowns, face shields and gloves.

Also running low were supplies like ventilators and some drugs necessary for putting people on those machines.

While advances have certainly been made, the country did not have enough time to build up those supply stores before new surges in the South and West. The result has been renewed worries that not enough PPE is available to keep healthcare workers safe.

Chaun Powell, group vice president of strategic supplier engagement at group purchasing organization Premier, said “conservation practices continue to be the key to this” as COVID-19 surges roll through the country. The longer those dire situations continue, the more stress is put on the supply chain before it has a chance to recover.

Premier’s most recent hospital survey found that more than half of respondents said N95s were heavily backordered. Almost half reported the same for isolation gowns and shoe covers.

Calderwood said there has been improvement, however. “We have a much longer days-on-hand PPE supply at this point and the other thing is, we’ve begun to manufacture some of our own PPE,” he said. “That’s something a number of hospitals have done in working with local companies.”

But the ability to manufacture new PPE in the U.S. also depends on the availability of raw materials, which are limited. That means significant advancements in domestic production are likely several months away, Powell said.

Health systems have stepped up the ability to coordinate and attempt to get equipment where it’s needed most, especially for big-ticket items like ventilators. Providers are more hesitant, however, to let go of PPE without the virus being better contained.

The backstop supposed to help hospitals during a crisis is the national stockpile, which the federal government is attempting to resupply. It doesn’t appear to be enough, though, at least not yet, Calderwood said.

“One thing that concerns me is we did have a national stockpile of PPE, and I get the sense that we’ve kind of burned through that supply,” he said. “And now we’re relying on private industry to meet the need.”

Another problem hospitals face as the pandemic drags on is maintaining adequate staffing levels. Doctors, nurses and other front-line employees are in incredibly stressful work environments. The great potential for burnout will exacerbate existing shortages, just as medical schools are still trying to figure out how to continue with training and education.

“Those areas are concerning to our hospitals because our hospitals depend on a whole myriad of medical staff,” Advis CEO Lyndean Brick said. “Whether it’s physicians, nurses, technicians, housekeepers — that whole staff complement is what’s at the core of healthcare. You can have all the technology in the world but if you don’t have somebody to run it that whole system falls apart.”

On top of that is the increase in labor strife as working conditions have deteriorated in some cases. Nurses have reported fearing for their safety among PPE shortages and alleged lapses in protocol. Brick said she expects strike threats and other actions to continue.

Changing workflows

When COVID-19 cases started ramping up for the first time in the U.S., hospitals throughout the country, acting on CMS advice, shut down elective procedures to prepare their facilities for a potential influx of critical patients with the disease. In some areas, hospitals did have to activate surge plans at that time. Others have done so more recently as the result of increases in the South and West.

But few have resorted to once again halting electives. Brick told Healthcare Dive she doesn’t expect that to change, mostly because hospitals have by and large figured out how to properly continue that care.

She trusts any that can’t do so safely, won’t try.

“For the majority of our providers, except in the occasional state where they’re having a real problem right now, I think that we’re going to see elective surgeries still continue,” Brick said. “Because most of our hospitals have capacity right now. They’re able to do this successfully and securely, and it’s really detrimental to patients to not get the care that they need.”

Hospitals rely on elective procedures to drive their revenue, an added motivation to find ways to keep them running even when COVID-19 is detected at greater levels in the community.

Intermountain, based in Salt Lake City, recently performed its 100th organ transplant of the year, ahead of last year’s pace despite the disruption of the COVID-19 crisis.

Alonso, the program director for abdominal transplants, said that while transplants are considered essential services, staff did pause some procedures when electives were halted and have re-evaluated workflow to be as safe as possible to patients, who are at higher risk after surgery because they are immunocompromised.

The hospital developed a triage system to help evaluate what services are necessary based on what level of COVID-19 spread is present in the community and how many beds and staffers are available to treat them.

The system’s main hospital has certain floors and employees designated for COVID-19 treatment. Staff have been reallocated for certain needs like testing and there are plans available if doctors and surgeons need to be deployed to the ICU.

As many outpatient visits as possible are being changed to virtual, but in the building, patients are screened for symptoms and required to wear masks and follow distancing protocols.

At the transplant center, doctors were at one point divided into teams in case someone got sick and coworkers had to self-isolate.

“We went through a dry run where, at the beginning, we shut down incredibly hard to see how we could do it operationally,” Alonso said. Intermountain hasn’t had to do that again, but is ready if such measures become necessary, she said.

Brick and others said that despite the genuinely frightening circumstance brought by the pandemic, hospitals’ responses have been admirable and providers have been quick to adapt. Slow or nonexistent leadership at the federal level, especially in sourcing and obtaining PPE, has been the bigger roadblock.

“Across the board, the whole healthcare industry has responded beautifully to this,” Brick said. “Where our country has fallen down is we don’t have a master plan to deal with this. Our federal leadership is reactionary, and we are not coordinating a master plan to deal with this in the long term. That’s where my concerns are at. My concerns are not at our local hospitals. They have their acts together.”