Health systems have a big challenge: rising costs and reimbursement that doesn’t keep up with inflation. The amount spent on healthcare annually continues to rise while outcomes aren’t meaningfully better.

Some people outside of the industry wonder: Why doesn’t healthcare just act more like other businesses?

“There seems to be a widely held belief that healthcare providers respond the same as all other businesses that face rising costs,” said Cliff Megerian, MD, CEO of University Hospitals in Cleveland. “That is absolutely not true. Unlike other businesses, hospitals and health systems cannot simply adjust prices in response to inflation due to pre-negotiated rates and government mandated pay structures. Instead, we are continually innovating approaches to population health, efficiency and cost management, ensuring that we maintain delivery of high quality care to our patients.”

Nonprofit hospitals are also responsible for serving all patients regardless of ability to pay, and University Hospitals is among the health systems distinguished as a best regional hospital for equitable access to care by U.S. News & World Report.

“This commitment necessitates additional efforts to ensure equitable access to healthcare services, which inherently also changes our payer mix by design,” said Dr. Megerian. “Serving an under-resourced patient base, including a significant number of Medicaid, underinsured and uninsured individuals, requires us to balance financial constraints with our ethical obligations to provide the highest quality care to everyone.”

Hospitals need adequate reimbursement to continue providing services while also staffing the hospital appropriately. Many hospitals and health systems have been in tense negotiations with insurers in the last 24 months for increased pay rates to cover rising costs.

“Without appropriate adjustments, nonprofit healthcare providers may struggle to maintain the high standards of care that patients deserve, especially when serving vulnerable populations,” said Dr. Megerian. “Ensuring fair reimbursement rates supports our nonprofit industry’s aim to deliver equitable, high quality healthcare to all while preserving the integrity of our health systems.”

Industry outsiders often seek free market dynamics in healthcare as the “fix” for an expensive and complicated system. But leaving healthcare up to the normal ebbs and flows of businesses would exclude a large portion of the population from services. Competition may lead to service cuts and hospital closures as well, which devastates communities.

“A misconception is that the marketplace and utilization of competitive business model will fix all that ails the American healthcare system,”

said Scot Nygaard, MD, COO of Lee Health in Ft. Myers and Cape Coral, Fla.

“Is healthcare really a marketplace, in which the forces of competition will solve for many of the complex problems we face, such as healthcare disparities, cost effective care, more uniform and predictive quality and safety outcomes, mental health access, professional caregiver workforce supply?”

Without comprehensive reform at the state or federal level, many health systems have been left to make small changes hoping to yield different results. But, Dr. Nygaard said, the “evidence year after year suggests that this approach is not successful and yet we fear major reform despite the outcomes.”

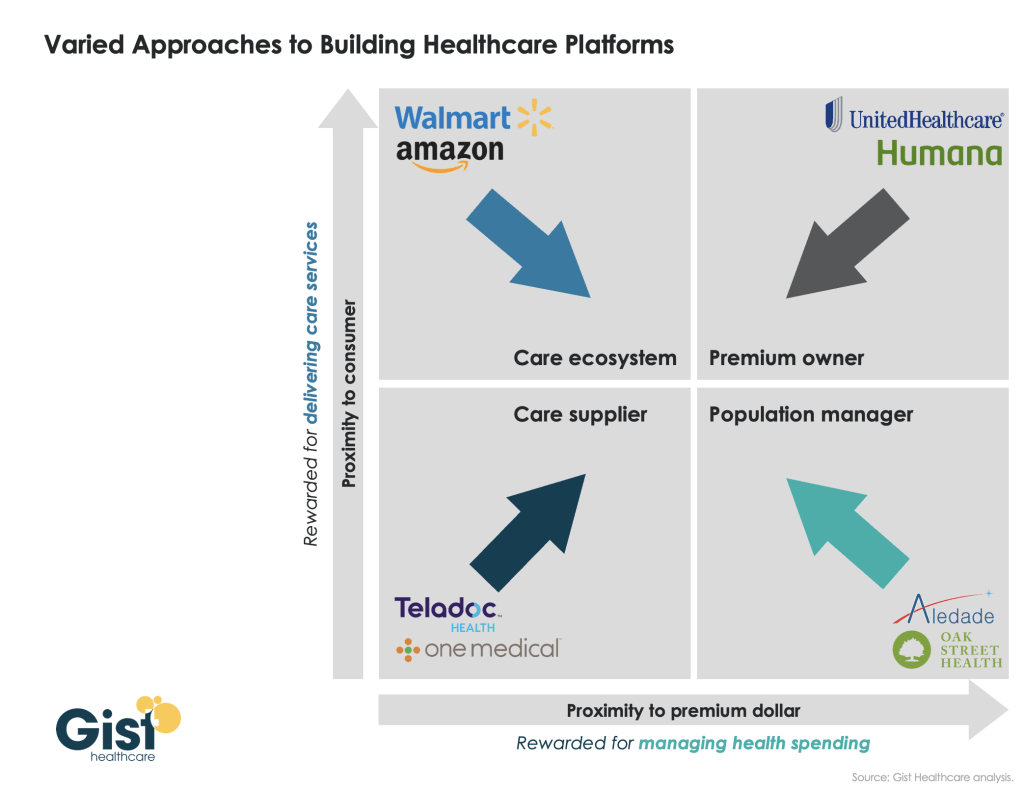

The dearth of outside companies trying to enter the healthcare space hasn’t helped. People now expect healthcare providers to function like Amazon or Walmart without understanding the unique complexities of the industry.

“Unlike retail, healthcare involves navigating intricate regulations, providing deeply personal patient interactions and building sustained trust,” said Andreia de Lima, MD, chief medical officer of Cayuga Health System in Ithaca, N.Y. “Even giants like Walmart found it challenging to make primary care profitable due to high operating costs and complex reimbursement systems. Success in healthcare requires more than efficiency; it demands a deep understanding of patient care, ethical standards and the unpredictable nature of human health.”

So what can be done?

Tracea Saraliev, a board member for Dominican Hospital Santa Cruz (Calif.) and PIH Health said leaders need to increase efforts to simplify and improve healthcare economics.

“Despite increased ownership of healthcare by consumers, the economics of healthcare remain largely misunderstood,” said Ms. Saraliev. “For example, consumers erroneously believe that they always pay less for care with health insurance. However, a patient can pay more for healthcare with insurance than without as a result of the negotiated arrangements hospitals have with insurance companies and the deductibles of their policy.”

There is also a variation in cost based on the provider, and even with financial transparency it’s a challenge to provide an accurate assessment for the cost of care before services. Global pricing and other value-based care methods streamline the price, but healthcare providers need great data to benefit from the arrangements.

Based on payer mix, geographic location and contracted reimbursement rates, some health systems are able to thrive while others struggle to stay afloat. The variation mystifies some people outside of the industry.

“Healthcare economics very much remains paradoxical to even the most savvy of consumers,” said Ms. Saraliev.