Cartoon – Blood Test Results

Of 26 health systems surveyed by MedCity News, nearly half used automated tools to respond to the Covid-19 pandemic, but none of them were regulated. Even as some hospitals continued using these algorithms, experts cautioned against their use in high-stakes decisions.

A year ago, Michigan Medicine faced a dire situation. In March of 2020, the health system predicted it would have three times as many patients as its 1,000-bed capacity — and that was the best-case scenario. Hospital leadership prepared for this grim prediction by opening a field hospital in a nearby indoor track facility, where patients could go if they were stable, but still needed hospital care. But they faced another predicament: How would they decide who to send there?

Two weeks before the field hospital was set to open, Michigan Medicine decided to use a risk model developed by Epic Systems to flag patients at risk of deterioration. Patients were given a score of 0 to 100, intended to help care teams determine if they might need an ICU bed in the near future. Although the model wasn’t developed specifically for Covid-19 patients, it was the best option available at the time, said Dr. Karandeep Singh, an assistant professor of learning health sciences at the University of Michigan and chair of Michigan Medicine’s clinical intelligence committee. But there was no peer-reviewed research to show how well it actually worked.

Researchers tested it on over 300 Covid-19 patients between March and May. They were looking for scores that would indicate when patients would need to go to the ICU, and if there was a point where patients almost certainly wouldn’t need intensive care.

“We did find a threshold where if you remained below that threshold, 90% of patients wouldn’t need to go to the ICU,” Singh said. “Is that enough to make a decision on? We didn’t think so.”

But if the number of patients were to far exceed the health system’s capacity, it would be helpful to have some way to assist with those decisions.

“It was something that we definitely thought about implementing if that day were to come,” he said in a February interview.

Thankfully, that day never came.

The survey

Michigan Medicine is one of 80 hospitals contacted by MedCity News between January and April in a survey of decision-support systems implemented during the pandemic. Of the 26 respondents, 12 used machine learning tools or automated decision systems as part of their pandemic response. Larger hospitals and academic medical centers used them more frequently.

Faced with scarcities in testing, masks, hospital beds and vaccines, several of the hospitals turned to models as they prepared for difficult decisions. The deterioration index created by Epic was one of the most widely implemented — more than 100 hospitals are currently using it — but in many cases, hospitals also formulated their own algorithms.

They built models to predict which patients were most likely to test positive when shortages of swabs and reagents backlogged tests early in the pandemic. Others developed risk-scoring tools to help determine who should be contacted first for monoclonal antibody treatment, or which Covid patients should be enrolled in at-home monitoring programs.

MedCity News also interviewed hospitals on their processes for evaluating software tools to ensure they are accurate and unbiased. Currently, the FDA does not require some clinical decision-support systems to be cleared as medical devices, leaving the developers of these tools and the hospitals that implement them responsible for vetting them.

Among the hospitals that published efficacy data, some of the models were only evaluated through retrospective studies. This can pose a challenge in figuring out how clinicians actually use them in practice, and how well they work in real time. And while some of the hospitals tested whether the models were accurate across different groups of patients — such as people of a certain race, gender or location — this practice wasn’t universal.

As more companies spin up these models, researchers cautioned that they need to be designed and implemented carefully, to ensure they don’t yield biased results.

An ongoing review of more than 200 Covid-19 risk-prediction models found that the majority had a high risk of bias, meaning the data they were trained on might not represent the real world.

“It’s that very careful and non-trivial process of defining exactly what we want the algorithm to be doing,” said Ziad Obermeyer, an associate professor of health policy and management at UC Berkeley who studies machine learning in healthcare. “I think an optimistic view is that the pandemic functions as a wakeup call for us to be a lot more careful in all of the ways we’ve talked about with how we build algorithms, how we evaluate them, and what we want them to do.”

Algorithms can’t be a proxy for tough decisions

Concerns about bias are not new to healthcare. In a paper published two years ago, Obermeyer found a tool used by several hospitals to prioritize high-risk patients for additional care resources was biased against Black patients. By equating patients’ health needs with the cost of care, the developers built an algorithm that yielded discriminatory results.

More recently, a rule-based system developed by Stanford Medicine to determine who would get the Covid-19 vaccine first ended up prioritizing administrators and doctors who were seeing patients remotely, leaving out most of its 1,300 residents who had been working on the front lines. After an uproar, the university attributed the errors to a “complex algorithm,” though there was no machine learning involved.

Both examples highlight the importance of thinking through what exactly a model is designed to do — and not using them as a proxy to avoid the hard questions.

“The Stanford thing was another example of, we wanted the algorithm to do A, but we told it to do B. I think many health systems are doing something similar,” Obermeyer said. “You want to give the vaccine first to people who need it the most — how do we measure that?”

The urgency that the pandemic created was a complicating factor. With little information and few proven systems to work with in the beginning, health systems began throwing ideas at the wall to see what works. One expert questioned whether people might be abdicating some responsibility to these tools.

“Hard decisions are being made at hospitals all the time, especially in this space, but I’m worried about algorithms being the idea of where the responsibility gets shifted,” said Varoon Mathur, a technology fellow at NYU’s AI Now Institute, in a Zoom interview. “Tough decisions are going to be made, I don’t think there are any doubts about that. But what are those tough decisions? We don’t actually name what constraints we’re hitting up against.”

The wild, wild west

There currently is no gold standard for how hospitals should implement machine learning tools, and little regulatory oversight for models designed to support physicians’ decisions, resulting in an environment that Mathur described as the “wild, wild west.”

How these systems were used varied significantly from hospital to hospital.

Early in the pandemic, Cleveland Clinic used a model to predict which patients were most likely to test positive for the virus as tests were limited. Researchers developed it using health record data from more than 11,000 patients in Ohio and Florida, including 818 who tested positive for Covid-19. Later, they created a similar risk calculator to determine which patients were most likely to be hospitalized for Covid-19, which was used to prioritize which patients would be contacted daily as part of an at-home monitoring program.

Initially, anyone who tested positive for Covid-19 could enroll in this program, but as cases began to tick up, “you could see how quickly the nurses and care managers who were running this program were overwhelmed,” said Dr. Lara Jehi, Chief Research Information Officer at Cleveland Clinic. “When you had thousands of patients who tested positive, how could you contact all of them?”

While the tool included dozens of factors, such as a patient’s age, sex, BMI, zip code, and whether they smoked or got their flu shot, it’s also worth noting that demographic information significantly changed the results. For example, a patient’s race “far outweighs” any medical comorbidity when used by the tool to estimate hospitalization risk, according to a paper published in Plos One. Cleveland Clinic recently made the model available to other health systems.

Others, like Stanford Health Care and 731-bed Santa Clara County Medical Center, started using Epic’s clinical deterioration index before developing their own Covid-specific risk models. At one point, Stanford developed its own risk-scoring tool, which was built using past data from other patients who had similar respiratory diseases, such as the flu, pneumonia, or acute respiratory distress syndrome. It was designed to predict which patients would need ventilation within two days, and someone’s risk of dying from the disease at the time of admission.

Stanford tested the model to see how it worked on retrospective data from 159 patients that were hospitalized with Covid-19, and cross-validated it with Salt Lake City-based Intermountain Healthcare, a process that took several months. Although this gave some additional assurance — Salt Lake City and Palo Alto have very different populations, smoking rates and demographics — it still wasn’t representative of some patient groups across the U.S.

“Ideally, what we would want to do is run the model specifically on different populations, like on African Americans or Hispanics and see how it performs to ensure it’s performing the same for different groups,” Tina Hernandez-Boussard, an associate professor of medicine, biomedical data science and surgery at Stanford, said in a February interview. “That’s something we’re actively seeking. Our numbers are still a little low to do that right now.”

Stanford planned to implement the model earlier this year, but ultimately tabled it as Covid-19 cases fell.

‘The target is moving so rapidly’

Although large medical centers were more likely to have implemented automated systems, there were a few notable holdouts. For example, UC San Francisco Health, Duke Health and Dignity Health all said they opted not to use risk-prediction models or other machine learning tools in their pandemic responses.

“It’s pretty wild out there and I’ll be honest with you — the dynamics are changing so rapidly,” said Dr. Erich Huang, chief officer for data quality at Duke Health and director of Duke Forge. “You might have a model that makes sense for the conditions of last month but do they make sense for the conditions of next month?”

That’s especially true as new variants spread across the U.S., and more adults are vaccinated, changing the nature and pace of the disease. But other, less obvious factors might also affect the data. For instance, Huang pointed to big differences in social mobility across the state of North Carolina, and whether people complied with local restrictions. Differing social and demographic factors across communities, such as where people work and whether they have health insurance, can also affect how a model performs.

“There are so many different axes of variability, I’d feel hard pressed to be comfortable using machine learning or AI at this point in time,” he said. “We need to be careful and understand the stakes of what we’re doing, especially in healthcare.”

Leadership at one of the largest public hospitals in the U.S., 600-bed LAC+USC Medical Center in Los Angeles, also steered away from using predictive models, even as it faced an alarming surge in cases over the winter months.

At most, the hospital used alerts to remind physicians to wear protective equipment when a patient has tested positive for Covid-19.

“My impression is that the industry is not anywhere near ready to deploy fully automated stuff just because of the risks involved,” said Dr. Phillip Gruber, LAC+USC’s chief medical information officer. “Our institution and a lot of institutions in our region are still focused on core competencies. We have to be good stewards of taxpayer dollars.”

When the data itself is biased

Developers have to contend with the fact that any model developed in healthcare will be biased, because the data itself is biased; how people access and interact with health systems in the U.S. is fundamentally unequal.

How that information is recorded in electronic health record systems (EHR) can also be a source of bias, NYU’s Mathur said. People don’t always self-report their race or ethnicity in a way that fits neatly within the parameters of an EHR. Not everyone trusts health systems, and many people struggle to even access care in the first place.

“Demographic variables are not going to be sharply nuanced. Even if they are… in my opinion, they’re not clean enough or good enough to be nuanced into a model,” Mathur said.

The information hospitals have had to work with during the pandemic is particularly messy. Differences in testing access and missing demographic data also affect how resources are distributed and other responses to the pandemic.

“It’s very striking because everything we know about the pandemic is viewed through the lens of number of cases or number of deaths,” UC Berkeley’s Obermeyer said. “But all of that depends on access to testing.”

At the hospital level, internal data wouldn’t be enough to truly follow whether an algorithm to predict adverse events from Covid-19 was actually working. Developers would have to look at social security data on mortality, or whether the patient went to another hospital, to track down what happened.

“What about the people a physician sends home — if they die and don’t come back?” he said.

Researchers at Mount Sinai Health System tested a machine learning tool to predict critical events in Covid-19 patients — such as dialysis, intubation or ICU admission — to ensure it worked across different patient demographics. But they still ran into their own limitations, even though the New York-based hospital system serves a diverse group of patients.

They tested how the model performed across Mount Sinai’s different hospitals. In some cases, when the model wasn’t very robust, it yielded different results, said Benjamin Glicksberg, an assistant professor of genetics and genomic sciences at Mount Sinai and a member of its Hasso Plattner Institute for Digital Health.

They also tested how it worked in different subgroups of patients to ensure it didn’t perform disproportionately better for patients from one demographic.

“If there’s a bias in the data going in, there’s almost certainly going to be a bias in the data coming out of it,” he said in a Zoom interview. “Unfortunately, I think it’s going to be a matter of having more information that can approximate these external factors that may drive these discrepancies. A lot of that is social determinants of health, which are not captured well in the EHR. That’s going to be critical for how we assess model fairness.”

Even after checking for whether a model yields fair and accurate results, the work isn’t done yet. Hospitals must continue to validate continuously to ensure they’re still working as intended — especially in a situation as fast-moving as a pandemic.

A bigger role for regulators

All of this is stirring up a broader discussion about how much of a role regulators should have in how decision-support systems are implemented.

Currently, the FDA does not require most software that provides diagnosis or treatment recommendations to clinicians to be regulated as a medical device. Even software tools that have been cleared by the agency lack critical information on how they perform across different patient demographics.

Of the hospitals surveyed by MedCity News, none of the models they developed had been cleared by the FDA, and most of the external tools they implemented also hadn’t gone through any regulatory review.

In January, the FDA shared an action plan for regulating AI as a medical device. Although most of the concrete plans were around how to regulate algorithms that adapt over time, the agency also indicated it was thinking about best practices, transparency, and methods to evaluate algorithms for bias and robustness.

More recently, the Federal Trade Commission warned that it could crack down on AI bias, citing a paper that AI could worsen existing healthcare disparities if bias is not addressed.

“My experience suggests that most models are put into practice with very little evidence of their effects on outcomes because they are presumed to work, or at least to be more efficient than other decision-making processes,” Kellie Owens, a researcher for Data & Society, a nonprofit that studies the social implications of technology, wrote in an email. “I think we still need to develop better ways to conduct algorithmic risk assessments in medicine. I’d like to see the FDA take a much larger role in regulating AI and machine learning models before their implementation.”

Developers should also ask themselves if the communities they’re serving have a say in how the system is built, or whether it is needed in the first place. The majority of hospitals surveyed did not share with patients if a model was used in their care or involve patients in the development process.

In some cases, the best option might be the simplest one: don’t build.

In the meantime, hospitals are left to sift through existing published data, preprints and vendor promises to decide on the best option. To date, Michigan Medicine’s paper is still the only one that has been published on Epic’s Deterioration Index.

Care teams there used Epic’s score as a support tool for its rapid response teams to check in on patients. But the health system was also looking at other options.

“The short game was that we had to go with the score we had,” Singh said. “The longer game was, Epic’s deterioration index is proprietary. That raises questions about what is in it.”

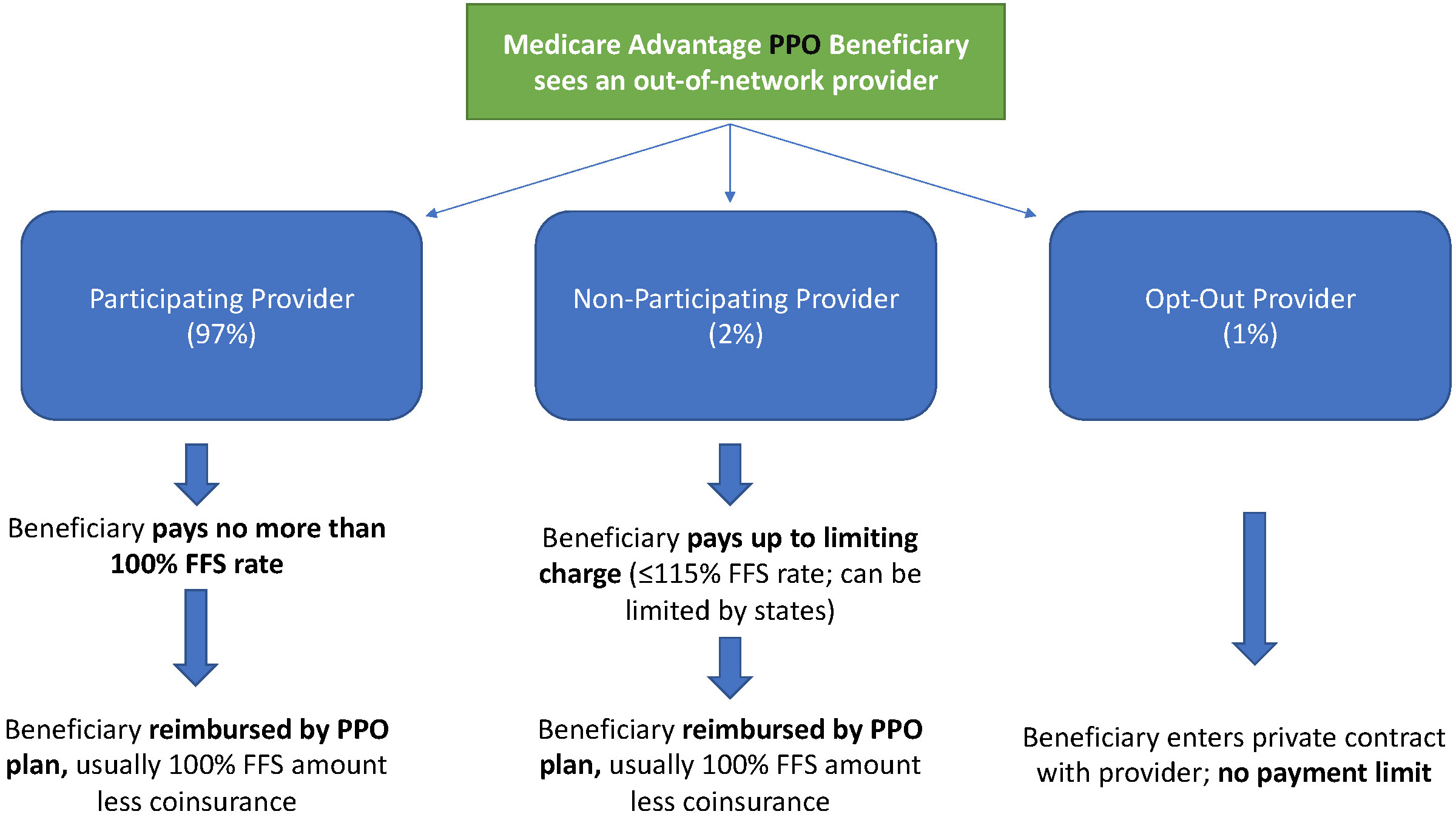

The complexity of Medicare Advantage (MA) physician networks has been well-documented, but the payment regulations that underlie these plans remain opaque, even to experts. If an MA plan enrollee sees an out-of-network doctor, how much should she expect to pay?

The answer, like much of the American healthcare system, is complicated. We’ve consulted experts and scoured nearly inscrutable government documents to try to find it. In this post we try to explain what we’ve learned in a much more accessible way.

Medicare Advantage Basics

Medicare Advantage is the private insurance alternative to traditional Medicare (TM), comprised largely of HMO and PPO options. One-third of the 60+ million Americans covered by Medicare are enrolled in MA plans. These plans, subsidized by the government, are governed by Medicare rules, but, within certain limits, are able to set their own premiums, deductibles, and service payment schedules each year.

Critically, they also determine their own network extent, choosing which physicians are in- or out-of-network. Apart from cost sharing or deductibles, the cost of care from providers that are in-network is covered by the plan. However, if an enrollee seeks care from a provider who is outside of their plan’s network, what the cost is and who bears it is much more complex.

Provider Types

To understand the MA (and enrollee) payment-to-provider pipeline, we first need to understand the types of providers that exist within the Medicare system.

Participating providers, which constitute about 97% of all physicians in the U.S., accept Medicare Fee-For-Service (FFS) rates for full payment of their services. These are the rates paid by TM. These doctors are subject to the fee schedules and regulations established by Medicare and MA plans.

Non-participating providers (about 2% of practicing physicians) can accept FFS Medicare rates for full payment if they wish (a.k.a., “take assignment”), but they generally don’t do so. When they don’t take assignment on a particular case, these providers are not limited to charging FFS rates.

Opt-out providers don’t accept Medicare FFS payment under any circumstances. These providers, constituting only 1% of practicing physicians, can set their own charges for services and require payment directly from the patient. (Many psychiatrists fall into this category: they make up 42% of all opt-out providers. This is particularly concerning in light of studies suggesting increased rates of anxiety and depression among adults as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic).

How Out-of-Network Doctors are Paid

So, if an MA beneficiary goes to see an out-of-network doctor, by whom does the doctor get paid and how much? At the most basic level, when a Medicare Advantage HMO member willingly seeks care from an out-of-network provider, the member assumes full liability for payment. That is, neither the HMO plan nor TM will pay for services when an MA member goes out-of-network.

The price that the provider can charge for these services, though, varies, and must be disclosed to the patient before any services are administered. If the provider is participating with Medicare (in the sense defined above), they charge the patient no more than the standard Medicare FFS rate for their services. Non-participating providers that do not take assignment on the claim are limited to charging the beneficiary 115% of the Medicare FFS amount, the “limiting charge.” (Some states further restrict this. In New York State, for instance, the maximum is 105% of Medicare FFS payment.) In these cases, the provider charges the patient directly, and they are responsible for the entire amount (See Figure 1.)

Alternatively, if the provider has opted-out of Medicare, there are no limits to what they can charge for their services. The provider and patient enter into a private contract; the patient agrees to pay the full amount, out of pocket, for all services.

MA PPO plans operate slightly differently. By nature of the PPO plan, there are built-in benefits covering visits to out-of-network physicians (usually at the expense of higher annual deductibles and co-insurance compared to HMO plans). Like with HMO enrollees, an out-of-network Medicare-participating physician will charge the PPO enrollee no more than the standard FFS rate for their services. The PPO plan will then reimburse the enrollee 100% of this rate, less coinsurance. (See Figure 2.)

In contrast, a non-participating physician that does not take assignment is limited to charging a PPO enrollee 115% of the Medicare FFS amount, which can be further limited by state regulations. In this case, the PPO enrollee is also reimbursed by their plan up to 100% (less coinsurance) of the FFS amount for their visit. Again, opt-out physicians are exempt from these regulations and must enter private contracts with patients.

Some Caveats

There are two major caveats to these payment schemes (with many more nuanced and less-frequent exceptions detailed here). First, if a beneficiary seeks urgent or emergent care (as defined by Medicare) and the provider happens to be out-of-network for the MA plan (regardless of HMO/PPO status), the plan must cover the services at their established in-network emergency services rates.

The second caveat is in regard to the declared public health emergency due to COVID-19 (set to expire in April 2021, but likely to be extended). MA plans are currently required to cover all out-of-network services from providers that contract with Medicare (i.e., all but opt-out providers) and charge beneficiaries no more than the plan-established in-network rates for these services. This is being mandated by CMS to compensate for practice closures and other difficulties of finding in-network care as a result of the pandemic.

Conclusion

Outside of the pandemic and emergency situations, knowing how much you’ll need to pay for out-of-network services as a MA enrollee depends on a multitude of factors. Though the vast majority of American physicians contract with Medicare, the intersection of insurer-engineered physician networks and the complex MA payment system could lead to significant unexpected costs to the patient.

Share this…

Kaiser Health News’ latest edition of its “Bill of the Month” series features a patient who was charged a “facility fee,” which drove up what she owed to more than 10 times higher than what she’d previously paid for the same care.

Why it matters: Facility fees — which are essentially room rental fees, as KHN puts it — are becoming increasingly controversial, and patients often receive the bill without warning.

What they’re saying: “Facility fees are designed by hospitals in particular to grab more revenue from the weakest party in health care: namely, the individual patient,” Alan Sager, a professor at the Boston University School of Public Health, told KHN.

https://mailchi.mp/3e9af44fcab8/the-weekly-gist-march-26-2021?e=d1e747d2d8

Large health insurers no longer just provide coverage, but are instead repositioning themselves as vertically integrated healthcare organizations that span the care continuum.

The graphic above shows five-year total revenue growth by segment for the top five health insurance companies.

Some, like Anthem and Humana, are still in the early stages of revenue diversification, leveraging partnerships and investments to fill service gaps—in Humana’s case, these are mainly centered on the Medicare Advantage population.

On the other hand, the insurance revenue of Cigna and CVS Health is already dwarfed by pharmacy benefit management (PBM) revenue (as well as retail clinic revenue for CVS).

UnitedHealth Group (UHG) is clearly leading the pack, with a robust revenue diversification and vertical integration strategy.

Its Optum subsidiary grew 62 percent over the last five years, nearly double the rate of its UnitedHealthcare insurance business. Already the largest employer of physicians in the country, Optum recently announced plans to acquire Massachusetts-based 715-physician group, Atrius Health. It also announced its intent to acquire Change Healthcare, one of the largest providers of revenue and payment cycle management solutions.

Given the outsized role of the Optum division in driving UHG’s growth and profitability, it may soon face a dilemma that other publicly traded, diversified companies have had to confront: shareholder demands to unlock value by spinning off the business into a separate company.

Central to fending off that kind of activism by shareholders: demonstrable steps to integrate the myriad businesses the company has acquired into a functional whole. Just as Amazon’s hugely profitable Web Services business has become a target of spin-off demands, so too, eventually, may UHG’s Optum.

https://mailchi.mp/d88637d819ee/the-weekly-gist-march-19-2021?e=d1e747d2d8

We had occasion this week, when asked to weigh in on a health system’s “primary care strategy”, to assert once again that primary care is not a thing.

We were being intentionally provocative to make a point: what we traditionally refer to as “primary care” is actually a collection of different services, or “jobs to be done” for a patient (to borrow a Clayton Christensen term).

These include a range of things: urgent care, chronic disease management, medication management, virtual care, women’s health services, pediatrics, routine maintenance, and on and on. What they have in common is that they’re a patient’s “first call”: the initial point of contact in the healthcare system for most things that most patients need. It’s a distinction with a difference, in our view.

If you set out to address “primary care strategy”, you’re going to end up in a discussion about physician manpower, practices, and economics at a level of generalization that often misses what patients really need. Rather than the traditional E pluribus unum (out of many, one) approach that many take, we’d advise an Ex uno plures (out of one, many) perspective.

Ask the question “What problems do patients have when they first contact the healthcare system?” and then strategize around and resource each of those problems in the way that best solves them. That doesn’t mean taking a completely fragmented approach—it’s essential to link each of those solutions together in a coherent ecosystem of care that helps with navigation and information flow (and reimbursement).

But continuing to perpetuate an entity called “primary care” increasingly seems like an antiquated endeavor, particularly as technology, payment, and consumer preferences all point to a more distributed and easily accessible model of care delivery.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-477514725-c4271ad485734ba6b84cae22be7833cf.jpg)

Fourteen defendants have been sentenced to more than 74 years in prison combined and ordered to pay $82.9 million in restitution for their roles in a $200 million healthcare scheme designed to get physicians to steer patients to Forest Park Medical Center, a now-defunct hospital in Dallas, the U.S. Justice Department announced March 19.

More than 21 defendants were charged in a federal indictment in 2016 for their alleged involvement in a bribe and kickback scheme that involved paying surgeons, lawyers and others for referring patients to FPMC’s facilities. Those involved in the scheme paid and/or received $40 million in bribes and kickbacks for referring patients, and the fraud resulted in FPMC collecting $200 million.

Several of the defendants, including a founder and former administrator of FPMC, were convicted at trial in April 2019 and sentenced last week. Other defendants pleaded guilty before trial.

Hospital manager and founder Andrew Beauchamp pleaded guilty in 2018 to conspiracy to pay healthcare bribes and commercial bribery, then testified for the government during his co-conspirators’ trial. He admitted that the hospital “bought surgeries” and then “papered it up to make it look good.” He was sentenced March 19 to 63 months in prison.

Wilton “Mac” Burt, a founder and managing partner of the hospital, was found guilty of conspiracy, paying kickbacks, commercial bribery in violation of the Travel Act and money laundering. He was sentenced March 17 to 150 months in prison.

Four surgeons, a physician and a nurse were among the other defendants sentenced last week for their roles in the scheme. Access a list of the defendants and their sentences here.

— At stake: scheduled payment reductions totalling $54 billion

Healthcare groups are applauding efforts being made in Congress to stop two different cuts to the Medicare budget — both of which are due to “sequestration” requirements — before it’s too late.

One cut, part of the normal budget process, is a 2% — or $18 billion — cut in the projected Medicare budget under a process known as “sequestration.” Sequestration allows for prespecified cuts in projected agency budget increases if Congress can’t agree on their own cuts. Medicare’s budget had been slated for a 2% sequester cut in fiscal year 2020; however, due to the pandemic and the accompanying increased healthcare needs, Congress passed a moratorium on the 2% cut. That moratorium is set to expire on April 1.

Another projected cut — this one for 4%, or $36 billion — will be triggered by the COVID relief bill, formally known as the American Rescue Plan Act. That legislation, which President Biden signed into law last Thursday, must conform to the PAYGO (pay-as-you-go) Act, which requires that any legislation that has a cost to it that is not otherwise offset must be offset by sequestration-style budget cuts to mandatory programs, including Medicare.

There are now several bills in Congress to address these pending cuts. H.R. 1868, co-sponsored by House Budget Committee chairman John Yarmuth (D-Ky.), House Ways & Means Committee chairman Richard Neal (D-Mass.), and House Energy & Commerce Committee chairman Frank Pallone Jr. (D-N.J.), among others, would get rid of the PAYGO Act requirement and extend the 2% Medicare sequester moratorium through the end of 2021.

Another bill, H.R. 315, introduced in January by Reps. Bradley Schneider (D-Ill.) and David McKinley (R-W.Va.), would extend the 2% sequester moratorium until the end of the public health emergency has been declared. In the Senate, S. 748, introduced Monday by senators Susan Collins (R-Maine) and Jeanne Shaheen (D-N.H.) would do the same.

“For many providers, the looming Medicare payment cuts would pose a further threat to their ability to stay afloat and serve communities during a time when they are most needed,” Shaheen said in a press release. “Congress should be doing everything in its power to prevent these cuts from taking effect during these challenging times, which is why I’m introducing this bipartisan legislation with Senator Collins. I urge the Senate to act at once to protect our health care providers and ensure they can continue their work on the frontlines of COVID-19.”

Not surprisingly, provider groups were happy about the actions in Congress. “MGMA [Medical Group Management Association] supports recent bipartisan, bicameral efforts to extend the 2% Medicare sequester moratorium for the duration of the COVID-19 public health emergency,” said Anders Gilberg, senior vice president for government affairs at MGMA, in a statement. “Without congressional action, the country’s medical groups will face a combined 6% sequester cut — a payment cut that is unsustainable given the financial hardships due to COVID-19 and keeping up with the cost of inflation.”

Leonard Marquez, senior director of government relations and legislative advocacy at the Association of American Medical Colleges, said in a statement that it was “critical” that Congress extend the 2% sequester moratorium “to help ensure hospitals, faculty physicians, and all providers have the necessary financial resources to continue providing quality care to COVID-19 and all patients ... While we are making progress against COVID-19, cutting provider payments in the middle of a pandemic could jeopardize the nation’s recovery.”

The American Medical Association (AMA) also urged Congress to prevent both the 2% and the 4% Medicare cuts. “We strongly oppose these arbitrary across-the-board Medicare cuts, and the predictably devastating impact they would have on many already distressed physician practices,” AMA executive vice president and CEO James Madara, MD, said in a letter sent to congressional leaders at the beginning of March.

In the letter, Madara noted that an AMA report, “Changes in Medicare Physician Spending During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” analyzed Medicare physician claims data and found spending dropped as much as 57% below expected pre-pandemic levels in April 2020.

“And, while Medicare spending on physician services partially recovered from the April low, it was still 12% less than expected by the end of June 2020,” he continued. “During the first half of 2020, the cumulative estimated reduction in Medicare physician spending associated with the pandemic was $9.4 billion (19%). Results from an earlier AMA-commissioned survey of 3,500 practicing physicians conducted from mid-July through August 2020 found that 81% of respondents were still experiencing lower revenue than before the pandemic.”

Not everyone is a fan of extending the 2% cut moratorium, however. “Bad idea,” said James Capretta, resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, a right-leaning think tank, at an event Tuesday on Medicare solvency sponsored by the Bipartisan Policy Center. “There’s plenty of give in the revenue streams of these systems that creating a precedent where we’re going to go back to the pre-sequester level — it’s better to move forward and if there are struggling systems out there, deal with it on an ad hoc basis rather than just across the board paying out a lot more money, which I don’t think is necessary.” He added, however, that he agreed with the bill to get rid of the 4% cut. “The bigger cut associated with PAYGO enforcement I think would be too much.”

A key Medicare advisory panel is calling for a 2% bump to Medicare payments for acute care hospitals for 2022 but no hike for physicians.

The report, released Monday from the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC)—which recommends payment policies to Congress—bases payment rate recommendations on data from 2019. However, the commission did factor in the pandemic when evaluating the payment rates and other policies in the report to Congress, including whether policies should be permanent or temporary.

“The financial stress on providers is unpredictable, although it has been alleviated to some extent by government assistance and rebounding service utilization levels,” the report said.

MedPAC recommended that targeted and temporary funding policies are the best way to help providers rather than a permanent hike for payments that gets increased over time.

“Overall, these recommendations would reduce Medicare spending while preserving beneficiaries’ access to high-quality care,” the report added.

MedPAC expects the effects of the pandemic, which have hurt provider finances due to a drop in healthcare use, to persist into 2021 but to be temporary.

It calls for a 2% update for inpatient and outpatient services for 2022, the same increase it recommended for 2021.

The latest report recommends no update for physicians and other professionals. The panel also does not want any hikes for four payment systems: ambulatory surgical centers, outpatient dialysis facilities, skilled nursing facilities and hospices.

MedPAC also recommends Congress reduce the aggregate hospice cap by 20% and that “ambulatory surgery centers be required to report cost data to [Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)],” the report said.

But it does call for long-term care hospitals to get a 2% increase and to reduce payments by 5% for home health and inpatient rehabilitation facilities.

The panel also explores the effects of any policies implemented under the COVID-19 public health emergency, which is likely to extend through 2021 and could continue into 2022.

For instance, CMS used the public health emergency to greatly expand the flexibility for providers to be reimbursed for telehealth services. Use of telehealth exploded during the pandemic after hesitancy among patients to go to the doctor’s office or hospital for care.

“Without legislative action, many of the changes will expire at the end of the [public health emergency],” the report said.

MedPAC recommends Congress temporarily continue some of the telehealth expansions for one to two years after the public health emergency ends. This will give lawmakers more time to gather evidence on the impact of telehealth on quality and Medicare spending.

“During this limited period, Medicare should temporarily pay for specified telehealth services provided to all beneficiaries regardless of their location, and it should continue to cover certain newly-covered telehealth services and certain audio-only telehealth services if there is potential for clinical benefit,” according to a release on the report.

After the public health emergency ends, Medicare should also return to paying the physician fee schedule’s facility rate for any telehealth services. This will ensure Medicare can collect data on the cost for providing the services.

“Providers should not be allowed to reduce or waive beneficiary cost-sharing for telehealth services after the [public health emergency],” the report said. “CMS should also implement other safeguards to protect the Medicare program and its beneficiaries from unnecessary spending and potential fraud related to telehealth.”

https://mailchi.mp/b0535f4b12b6/the-weekly-gist-march-12-2021?e=d1e747d2d8

Many physician practices weathered 2020 better than they would have predicted last spring. We had anticipated many doctors would look to health systems or payers for support, but the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans kept practices going until patient volume returned. But as they now see an end to the pandemic, many doctors are experiencing a new round of uncertainty about the future. Post-pandemic fatigue, coupled with a long-anticipated wave of retiring Baby Boomer partners, is leading many more independent practices to consider their options. And layered on top of this, private equity investors are injecting a ton of money into the physician market, extending offers that leave some doctors feeling, according to one doctor we spoke with, that “you’d have to be an idiot to say no to a deal this good”.

2021 is already shaping up to be a record year for physician practice deals. But some of our recent conversations made us wonder if we had time-traveled back to the early 2000s, when hospital-physician partnerships were dominated by bespoke financial arrangements aimed at securing call coverage and referrals. Some health system leaders are flustered by specialist practices wanting a quick response to an investor proposal. Hospitals worry the joint ventures or co-management agreements that seemed to work well for years may not be enough, and wonder if they should begin recruiting new doctors or courting competitors, “just in case” current partners might jump ship for a better deal.

In contrast to other areas of strategy, where a ten-year vision can guide today’s decisions, it has always been hard for health systems to take the long view with physician partnerships.

When most “strategies” are really just responses to the fires of the day, health systems run the risk of relationships devolving to mere economic terms. Health systems may find themselves once again with a messy patchwork of doctors aligned by contractual relationships, rather than a tight network of physician partners who can work together to move care forward.