https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/finance/state-by-state-breakdown-of-130-rural-hospital-closures.html

Nearly one in five Americans live in rural areas and depend on their local hospital for care. Over the past 10 years, 130 of those hospitals have closed.

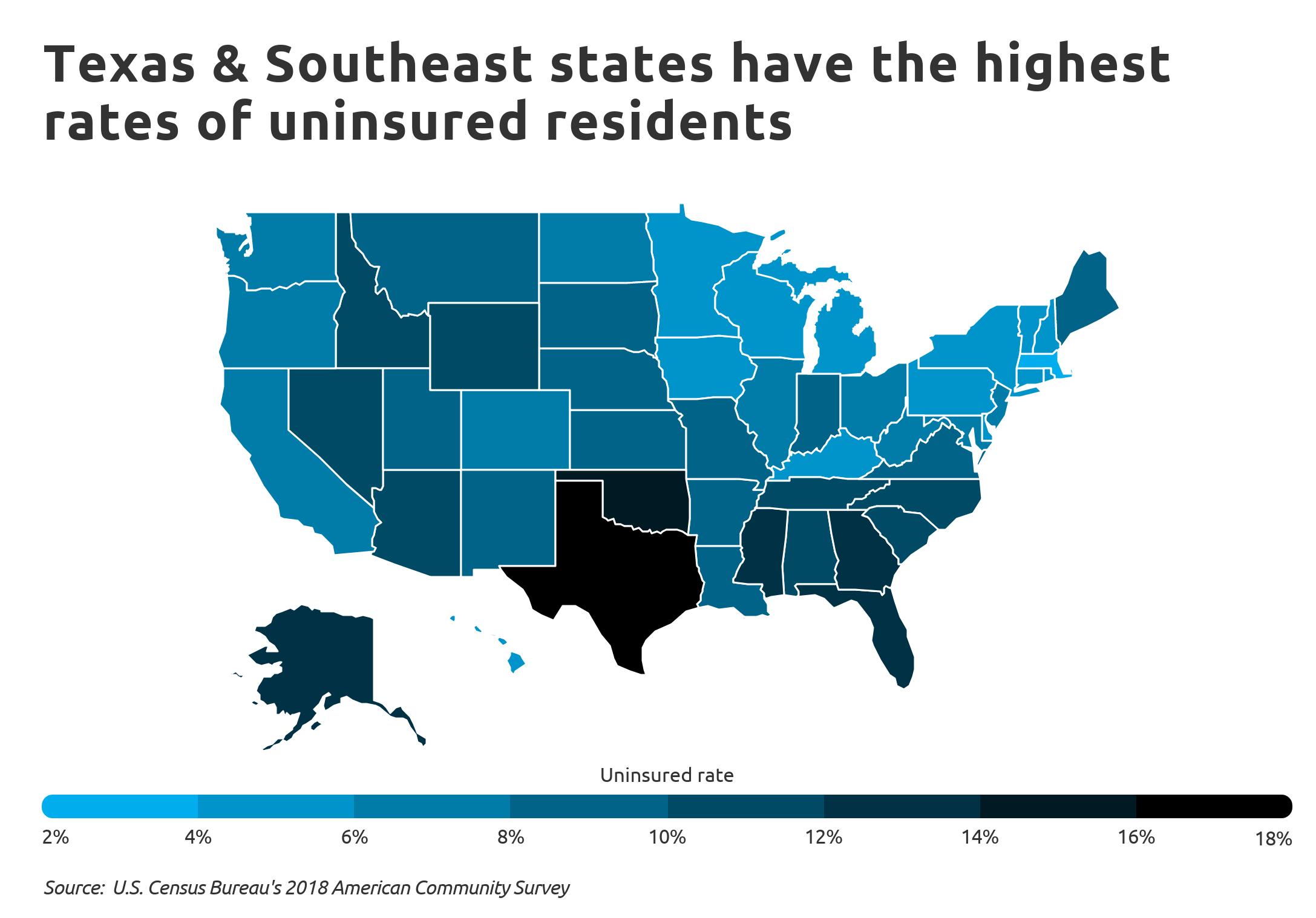

Thirty-three states have seen at least one rural hospital shut down since 2010, and the closures are heavily clustered in states that have not expanded Medicaid under the ACA, according to the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research.

Twenty-one rural hospitals in Texas have closed since 2010, the most of any state. Tennessee has the second-most closures, with 13 rural hospitals shutting down in the past decade. In third place is Oklahoma with eight closures.

Listed below are the 130 rural hospitals that have closed since Jan. 1, 2010, as tracked by the Sheps Center. For the purposes of its analysis, the Sheps Center defined a hospital closure as the cessation in the provision of inpatient services.

“We follow the convention of the Office of Inspector General that a closed hospital is ‘a facility that stopped providing general, short-term, acute inpatient care,'” reads a statement on the Sheps Center’s website. “We did not consider a hospital closed if it: merged with, or was sold to, another hospital but the physical plant continued to provide inpatient acute care, converted to critical access status, or both closed and reopened during the same calendar year and at the same physical location.”

As of June 8, all the facilities listed below had stopped providing inpatient care. However, some of them still offered other services, including outpatient care, emergency care, urgent care or primary care.

Alabama

SouthWest Alabama Medical Center (Thomasville)

Randolph Medical Center (Roanoke)

Chilton Medical Center (Clanton)

Florence Memorial Hospital

Elba General Hospital

Georgiana Medical Center

Alaska

Sitka Community Hospital

Arizona

Cochise Regional Hospital (Douglas)

Hualapai Mountain Medical Center (Kingman)

Florence Community Healthcare

Arkansas

De Queen Medical Center

California

Kingsburg Medical Center

Corcoran District Hospital

Adventist Health Feather River (Paradise)

Coalinga Regional Medical Center

Florida

Campbellton-Graceville Hospital

Regional General Hospital (Williston)

Shands Live Oak Regional Medical Center

Shands Starke Regional Medical Center

Georgia

Hart County Hospital (Harwell)

Charlton Memorial Hospital (Folkston)

Calhoun Memorial Hospital (Arlington)

Stewart-Webster Hospital (Richland)

Lower Oconee Community Hospital (Glenwood)

North Georgia Medical Center (Ellijay)

Illinois

St. Mary’s Hospital (Streator)

Indiana

Fayette Regional Health System

Kansas

Central Kansas Medical Center (Great Bend)

Mercy Hospital Independence

Mercy Hospital Fort Scott

Horton Community Hospital

Oswego Community Hospital

Sumner Community Hospital (Wellington)

Kentucky

Nicholas County Hospital (Carlisle)

Parkway Regional Hospital (Fulton)

New Horizons Medical Center (Owenton)

Westlake Regional Hospital (Columbia)

Louisiana

Doctor’s Hospital at Deer Creek (Leesville)

Maine

St. Andrews Hospital (Boothbay Harbor)

Southern Maine Health Care-Sanford Medical Center

Parkview Adventist Medical Center (Brunswick)

Maryland

Edward W. McCready Memorial Hospital (Crisfield)

Massachusetts

North Adams Regional Hospital

Michigan

Cheboygan Memorial Hospital

Minnesota

Lakeside Medical Center

Albany Area Hospital

Albert Lea-Mayo Clinic Health System

Mayo Clinic Health System-Springfield

Mississippi

Patient’s Choice Medical of Humphreys County (Belzoni)

Pioneer Community Hospital of Newton

Merit Health Natchez-Community Campus

Kilmichael Hospital

Quitman County Hospital (Marks)

Missouri

Sac-Osage Hospital (Osceola)

Parkland Health Center-Weber Road (Farmington)

Southeast Health Center of Reynolds County (Ellington)

Southeast Health Center of Ripley County (Doniphan)

Twin Rivers Regional Medical Center (Kennett)

I-70 Community Hospital (Sweet Springs)

Pinnacle Regional Hospital (Boonville)

Nebraska

Tilden Community Hospital

Nevada

Nye Regional Medical Center (Tonopah)

New York

Lake Shore Health Care Center

Moses-Ludington Hospital (Ticonderoga)

North Carolina

Blowing Rock Hospital

Vidant Pungo Hospital (Belhaven)

Novant Health Franklin Medical Center (Louisburg)

Yadkin Valley Community Hospital (Yadkinville)

Our Community Hospital (Scotland Neck)

Sandhills Regional Medical Center (Hamlet)

Davie Medical Center-Mocksville

Ohio

Physicians Choice Hospital-Fremont

Doctors Hospital of Nelsonville

Oklahoma

Muskogee Community Hospital

Epic Medical Center (Eufaula)

Memorial Hospital & Physician Group (Frederick)

Latimer County General Hospital (Wilburton)

Pauls Valley General Hospital

Sayre Community Hospital

Haskell County Community Hospital (Stigler)

Mercy Hospital El Reno

Pennsylvania

Saint Catherine Medical Center Fountain Springs (Ashland)

Mid-Valley Hospital (Peckville)

Ellwood City Medical Center

UPMC Susquehanna Sunbury

South Carolina

Bamberg County Memorial Hospital

Marlboro Park Hospital (Bennettsville)

Southern Palmetto Hospital (Barnwell)

Fairfield Memorial Hospital (Winnsboro)

South Dakota

Holy Infant Hospital (Hoven)

Tennessee

Riverview Regional Medical Center South (Carthage)

Starr Regional Medical Center-Etowah

Haywood Park Community Hospital (Brownsville)

Gibson General Hospital (Trenton)

Humboldt General Hospital

United Regional Medical Center (Manchester)

Parkridge West Hospital (Jasper)

Tennova Healthcare-McNairy Regional (Selmer)

Copper Basin Medical Center (Copperhill)

McKenzie Regional Hospital

Jamestown Regional Medical Center

Takoma Regional Hospital (Greeneville)

Decatur County General Hospital (Parsons)

Texas

Wise Regional Health System-Bridgeport

Shelby Regional Medical Center

Renaissance Hospital Terrell

East Texas Medical Center-Mount Vernon

East Texas Medical Center-Clarksville

East Texas Medical Center-Gilmer

Good Shepherd Medical Center (Linden)

Lake Whitney Medical Center (Whitney)

Hunt Regional Community Hospital of Commerce

Gulf Coast Medical Center (Wharton)

Nix Community General Hospital (Dilley)

Weimar Medical Center

Care Regional Medical Center (Aransas Pass)

East Texas Medical Center-Trinity

Little River Healthcare Cameron Hospital

Little River Healthcare Rockdale Hospital

Stamford Memorial Hospital

Texas General-Van Zandt Regional Medical Center (Grand Saline)

Hamlin Memorial Hospital

Chillicothe Hospital

Central Hospital of Bowie

Virginia

Lee Regional Medical Center (Pennington Gap)

Pioneer Community Hospital of Patrick County (Stuart)

Mountain View Regional Hospital (Norton)

West Virginia

Williamson Memorial Hospital

Fairmont Regional Medical Center

Wisconsin

Franciscan Skemp Medical Center (Arcadia)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13249599/GettyImages_984402230.jpg)