Cartoon – Taking One for the Team

It was 5 a.m., not a hint of sun in the Houston sky, as Randy Young and his mom pulled into the line for a free Thanksgiving meal. They were three hours early. Hundreds of cars and trucks already idled in front of them outside NRG Stadium. This was where Young worked before the pandemic. He was a stadium cook. Now, after losing his job and struggling to get by, he and his 80-year-old mother hoped to get enough food for a holiday meal.

“It’s a lot of people out here,” said Young, 58. “I was just telling my mom, ‘You look at people pulling up in Mercedes and stuff, come on.’ If a person driving a Mercedes is in need of food, you know it’s bad.”

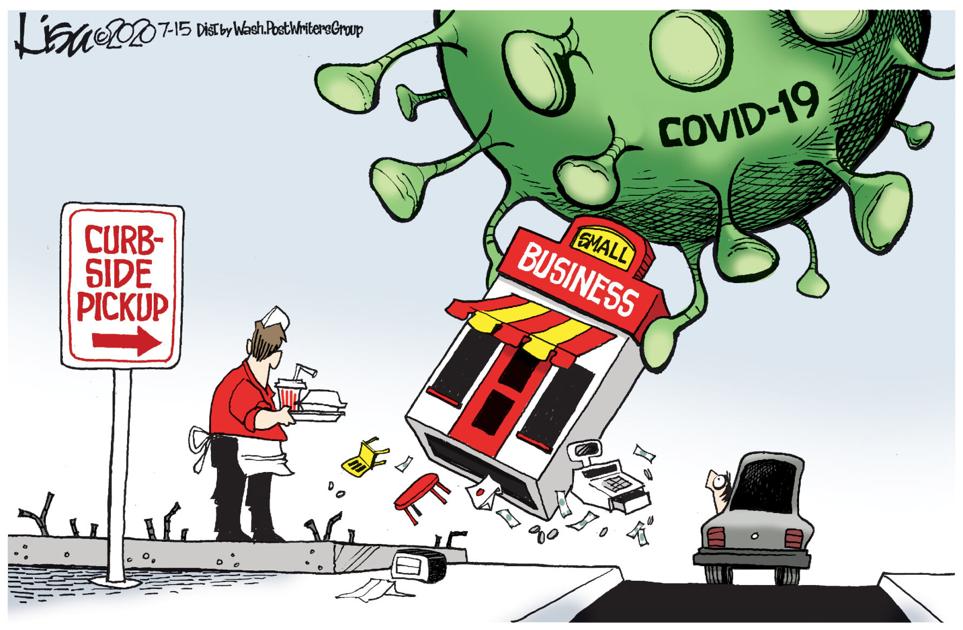

More Americans are going hungry now than at any point during the deadly coronavirus pandemic, according to a Post analysis of new federal data — a problem created by an economic downturn that has tightened its grip on millions of Americans and compounded by government relief programs that expired or will terminate at the end of the year. Experts say it is likely that there’s more hunger in the United States today than at any point since 1998, when the Census Bureau began collecting comparable data about households’ ability to get enough food.

One in 8 Americans reported they sometimes or often didn’t have enough food to eat in the past week, hitting nearly 26 million American adults, an increase several times greater than the most comparable pre-pandemic figure, according to Census Bureau survey data collected in late October and early November. That number climbed to more than 1 in 6 adults in households with children.

“It’s been driven by the virus and the unpredictable government response,” said Jeremy K. Everett, executive director of the Baylor Collaborative on Hunger and Poverty in Waco, Tex.

Nowhere has there been a hunger surge worse than in Houston, with a metro-area population of 7 million people. Houston was pulverized in summer when the coronavirus overwhelmed hospitals, and the local economy was been particularly hard hit by weak oil prices, making matters worse.

More than 1 in 5 adults in Houston reported going hungry recently, including 3 in 10 adults in households with children. The growth in hunger rates has hit Hispanic and Black households harder than White ones, a devastating consequence of a weak economy that has left so many people trying to secure food even during dangerous conditions.

On Saturday, these statistics manifested themselves in the thousands of cars waiting in multiple lines outside NRG Stadium. The people in these cars represented much of the country. Old. Young. Black. White. Asian. Hispanic. Families. Neighbors. People all alone.

Inside a maroon Hyundai Santa Fe was Neicie Chatman, 68, who had been waiting since 6:20 a.m., listening to recordings of a minister’s sermon piped into large earphones.

“I’ve been feeding my spirit,” she said.

Her hours at her job as an administrator have been unsteady since the pandemic began. Her sister was laid off. They both live with their mother, who has been sick for the past year. She planned to take the food home to feed her family and share with her older neighbors.

— Randy Young

— Adriana Contreras

Now, a new wave of coronavirus infections threatens more economic pain.

Yet the hunger crisis seems to have escaped widespread notice in a nation where millions of households have weathered the pandemic relatively untouched. The stock market fell sharply in March before roaring back and has recovered all of its losses. This gave the White House and some lawmakers optimism about the economy’s condition. Congress left for its Thanksgiving break without making any progress on a new pandemic aid deal even as food banks across the country report a crush of demand heading into the holidays.

“The hardship is incredibly widespread. Large parts of America are saying, ‘I couldn’t afford food for my family,’ ” said Stacy Dean, who focuses on food-assistance policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “It’s disappointing this hasn’t broken through.”

No place has been spared. In one of the nation’s richest counties, not far from Trump National Golf Club in Virginia, Loudoun Hunger Relief provided food to a record 887 households in a single week recently. That’s three times the Leesburg, Va.-based group’s pre-pandemic normal.

“We are continuing to see people who have never used our services before,” said Jennifer Montgomery, the group’s executive director.

Hunger rates spiked nationwide after shutdowns in late March closed large chunks of the U.S. economy. The situation improved somewhat as businesses reopened and the benefits from a $2.2 trillion federal pandemic aid package flowed into people’s pockets, with beefed-up unemployment benefits, support for food programs and incentives for companies to keep workers on the payroll.

But those effects were short-lived. The bulk of the federal aid had faded by September. And more than 12 million workers stand to lose unemployment benefits before year’s end if Congress doesn’t extend key programs.

“Everything is a disaster,” said Northwestern University economist Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, a leading expert on the economics of food insecurity. “I’m usually a pleasant person, but this is just crazy.”

Economic conditions are the main driver behind rising rates of hunger, but other factors play a role, Schanzenbach said. In the Great Recession that began in 2008, people received almost two years of unemployment aid — which helped reduce hunger rates. Some long-term unemployed workers qualified for even more help.

But the less-generous benefits from the pandemic unemployment assistance programs passed by Congress in March have already disappeared or soon will for millions of Americans.

Even programs that Congress agreed to extend have stumbled. A program giving families additional cash assistance to replace school meals missed by students learning at home was renewed for a year on Oct. 1. But the payments were delayed because many states still needed to get the U.S. Agriculture Department’s approval for their plans. The benefit works out to only about $6 per student for each missed school day. But experts say the program has been a lifeline for struggling families.

One program that has continued to provide expanded emergency benefits is the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP. The Agriculture Department issued an emergency order allowing states to provide more families the maximum benefit and to suspend the time limit on benefits for younger unemployed adults without children.

The sharpest rise in hunger was reported by groups who have long experienced the highest levels of it, particularly Black Americans. Twenty-two percent of Black U.S. households reported going hungry in the past week, nearly twice the rate faced by all American adults and more than two-and-a-half times the rate for White Americans.

The Houston area was posting some of its lowest hunger rates before the pandemic, thanks to a booming economy and a strong energy sector, Everett said. Then, the pandemic hit. Hunger surged, concentrated among the city’s sizable low-income population, in a state that still allows for the federally mandated minimum wage of $7.25 an hour. Houston’s hunger rates — like those nationwide — fell significantly after the $1,200 stimulus checks were mailed out in April and other pandemic aid plans took effect, Everett said.

But most of the effects of that aid are gone.

“Without sustained aid at the federal level, we’ll be hard pressed to keep up,” said Celia Call, chief executive of Feeding Texas, which advocates for 21 food banks in the state. “We’re just bracing for the worst.”

Schools are one of the most important sources of food for low-income families in Houston. The Houston Independent School District has 210,000 students — many of whom qualify for free or reduced-priced meals. But the pandemic closed schools in the spring. They reopened in the fall with less than half of the students choosing a hybrid model of in-school and at-home instruction. That has made feeding these children a difficult task.

“We’ve made an all-out effort to capture these kids and feed them,” said Betti Wiggins, the school district’s nutrition services officer.

The district provided curbside meal pickups outside schools. Anyone could come, not just schoolchildren. School staffers set up neighborhood distribution sites in the areas with the highest need. They started a program to serve meals to children living in apartment buildings. Sometimes the meal program required police escorts.

“I’m doing everything but serving in the gas station when they’re pumping the gas,” Wiggins said.

Wiggins said the normal school meals program she ran before the pandemic has been transformed into providing food for entire families far beyond a school’s walls. She has noticed unfamiliar faces in her meal lines. The “new poor,” she calls them, parents who might have worked in the airline or energy industries crushed by the pandemic.

“I’m seeing folks who don’t know how to handle the poverty thing,” she said, adding that it became her mission to make sure they had food.

The Houston Food Bank is the nation’s largest, serving 18 counties in Southeast Texas with help from 1,500 partner agencies. Last month, the food bank distributed 20.6 million pounds of food — down from the 27.8 million pounds handed out in May, but still 45 percent more than what it distributed in October 2019, with no end in sight.

The biggest worry for food banks right now is finding enough food, said Brian Greene, president of the Houston Food Bank. Food banks buy bulk food with donations. They take in donated food items, too. Food banks also benefited from an Agriculture Department program that purchased excess food from U.S. farmers hurt by the ongoing trade war with China, typically apples, milk and pork products. But funding for that program ended in September. Other federal pandemic programs are still buying hundreds of millions of dollars in food and donating it to food banks. But Greene said he worries about facing “a commodity cliff” even as demand grows.

Teresa Croft, who volunteers at a food distribution site at a church in the Houston suburb of Manvel, said the need is still overwhelming. She handles the paperwork for people visiting the food bank for the first time. They’re often embarrassed, she said. They never expected to be there. Sometimes, Croft tries to make them feel better by telling her own story — how she started at the food bank as a client, but got back on her feet financially more than a decade ago and is now a food bank volunteer.

“They feel so bad they’re having to ask for help. I tell them they shouldn’t feel bad. We’re all in this together,” Croft said. “If you need it, you need it.”

The pandemic changed how the Houston Food Bank runs. Everything is drive-through and walk-up. Items are preselected and bagged. The food bank has held several food distribution events in the parking lots outside NRG Stadium — a $325 million, retractable-roof temple to sports and home to the National Football League’s Houston Texans.

Last weekend, instead of holding the 71st annual Thanksgiving Day Parade in Houston, the city and H-E-B supermarkets decided to sponsor the food bank’s distribution event at NRG Stadium. The plan was to feed 5,000 families.

The first cars arrived at the stadium around 1 a.m. Saturday, long before the gates opened for the 8 a.m. event. By the time Young and his mother drove up, the line of vehicles stretched into the distance. Organizers opened the gates early. The cars and trucks began to slowly snake through the stadium’s parking lot toward a series of white tents, where the food was loaded into trunks by volunteers. The boxes contained enough food for multiple meals during the holiday week, with canned vegetables such as corn and sweet potatoes, a package of rolls, cranberry sauce and a box of masks. People picking up food were also given a bag of cereal and some resealable bags, a ham, a gallon of milk, and finally a turkey and pumpkin pie.

The food for 5,000 families ran out. The Houston Food Bank — knowing that would not be enough — was able to assemble more.

It provided food to 7,160 vehicles and 261 people who walked up to the event.

Troy Coakley, 56, came to the event looking for food to feed his family for the week. He still had his job breaking apart molds at a plant that makes parts for oil field and water companies. But his hours were cut when the economy took a hit in March. Coakley went from working overtime to three days a week.

He was struggling. Behind on rent. Unsure what was to come.

But for the moment, his trunk filled with food, he had one less thing to worry about.

“Other than [the pandemic], we were doing just fine,” Coakley said. “But now it’s getting worse and worse.”

Detroit Medical Center is laying off employees, and its parent company, Dallas-based Tenet Healthcare, is planning to sell or close four urgent care centers in the Detroit area, according to Crain’s Detroit Business.

Detroit Medical Center officials told Crain’s layoffs have occurred, but they declined to disclose the number of employees affected. Sources told Crain’s several hundred DMC employees have been laid off with more expected this year. Clinical staff, administrative assistants and employees at the management level were reportedly affected by the layoffs.

“Like many health systems locally and nationally, we continually evaluate and review our staffing needs, which have decreased due to reduced patient demand during the pandemic,” DMC said in a statement to Becker’s Hospital Review. “Our goal is to ensure we are strongly positioned to provide the highest quality and safest care to our patients while making the best use of our resources.”

Tenet is also planning to sell or close its four remaining MedPost urgent care centers in the Detroit area. Tenet has reached agreements to sell three of the urgent care centers in Bloomfield, Livonia and Southfield, Mich., to First Choice Urgent Care, a company spokesperson told Becker’s Hospital Review.

“We expect all employees in good standing to be offered positions to remain at the facilities upon completion of the sale, which we anticipate occurring in December,” the spokesperson told Becker’s.

The MedPost urgent care center in Rochester Hills, Mich., will close in December, the spokesperson said. Tenet may convert it to a physician office or other type of healthcare facility.

“We are committed to providing our full support and assistance to employees through the close, and facilitating opportunities for open roles at local Tenet facilities,” the spokesperson told Becker’s.

Tenet, a 65-hospital system, operated nine MedPost urgent care centers in the Detroit area at the beginning of the year. It closed five of the centers in April due to challenges linked to the COVID-19 pandemic. The MedPost urgent care centers are not part of DMC.

The financial challenges caused by the COVID-19 pandemic have forced hundreds of hospitals across the nation to furlough, lay off or reduce pay for workers, and others have had to scale back services or close.

Lower patient volumes, canceled elective procedures and higher expenses tied to the pandemic have created a cash crunch for hospitals. U.S. hospitals are estimated to lose more than $323 billion this year, according to a report from the American Hospital Association. The total includes $120.5 billion in financial losses the AHA predicts hospitals will see from July to December.

Hospitals are taking a number of steps to offset financial damage. Executives, clinicians and other staff are taking pay cuts, capital projects are being put on hold, and some employees are losing their jobs. More than 260 hospitals and health systems furloughed workers this year and dozens of others have implemented layoffs.

Below are 11 hospitals and health systems that announced layoffs since Sept. 1, most of which were attributed to financial strain caused by the pandemic.

1. NorthBay Healthcare, a nonprofit health system based in Fairfield, Calif., is laying off 31 of its 2,863 employees as part of its pandemic recovery plan, the system announced Nov. 2.

2. Minneapolis-based Children’s Minnesota is laying off 150 employees, or about 3 percent of its workforce. Children’s Minnesota cited several reasons for the layoffs, including the financial hit from the COVID-19 pandemic. Affected employees will end their employment either Dec. 31 or March 31.

3. Brattleboro Retreat, a psychiatric and addiction treatment hospital in Vermont, notified 85 employees in late October that they would be laid off within 60 days.

4. Citing a need to offset financial losses, Minneapolis-based M Health Fairview said it plans to downsize its hospital and clinic operations. As a result of the changes, 900 employees, about 3 percent of its 34,000-person workforce, will be laid off.

5. Lake Charles (La.) Memorial Health System laid off 205 workers, or about 8 percent of its workforce, as a result of damage sustained from Hurricane Laura. The health system laid off employees at Moss Memorial Health Clinic and the Archer Institute, two facilities in Lake Charles that sustained damage from the hurricane.

6. Burlington, Mass.-based Wellforce laid off 232 employees as a result of operating losses linked to the COVID-19 pandemic. The health system, comprising Tufts Medical Center, Lowell General Hospital and MelroseWakefield Healthcare, experienced a drastic drop in patient volume earlier this year due to the suspension of outpatient visits and elective surgeries. In the nine months ended June 30, the health system reported a $32.2 million operating loss.

7. Baptist Health Floyd in New Albany, Ind., part of Louisville, Ky.-based Baptist Health, eliminated 36 positions. The hospital said the cuts, which primarily affected administrative and nonclinical roles, are due to restructuring that is “necessary to meet financial challenges compounded by COVID-19.”

8. Cincinnati-based UC Health laid off about 100 employees. The job cuts affected both clinical and non-clinical staff. A spokesperson for the health system said no physicians were laid off.

9. Mercy Iowa City (Iowa) announced in September that it will lay off 29 employees to address financial strain tied to the COVID-19 pandemic.

10. Springfield, Ill.-based Memorial Health System laid off 143 employees, or about 1.5 percent of the five-hospital system’s workforce. The health system cited financial pressures tied to the pandemic as the reason for the layoffs.

11. Watertown, N.Y.-based Samaritan Health announced Sept. 8 that it laid off 51 employees and will make other cost-cutting moves to offset financial stress tied to the COVID-19 pandemic.

A complete financial recovery for many organizations is still far away, findings from Kaufman Hall indicate.

For the past three years, Kaufman Hall has released annual healthcare performance reports illustrating how hospitals and health systems are managing, both financially and operationally.

This year, however, with the pandemic altering the industry so broadly, the report took a different approach: to see how COVID-19 impacted hospitals and health systems across the country. The report’s findings deal with finances, patient volumes and recovery.

The report includes survey answers from respondents almost entirely (96%) from hospitals or health systems. Most of the respondents were in executive leadership (55%) or financial roles (39%). Survey responses were collected in August 2020.

FINANCIAL IMPACT

Findings from the report indicate that a complete financial recovery for many organizations is still far away. Almost three-quarters of the respondents said they were either moderately or extremely concerned about their organization’s financial viability in 2021 without an effective vaccine or treatment.

Looking back on the operating margins for the second quarter of the year, 33% of respondents saw their operating margins decline by more than 100% compared to the same time last year.

Revenue cycles have taken a hit from COVID-19, according to the report. Survey respondents said they are seeing increases in bad debt and uncompensated care (48%), higher percentages of uninsured or self-pay patients (44%), more Medicaid patients (41%) and lower percentages of commercially insured patients (38%).

Organizations also noted that increases in expenses, especially for personal protective equipment and labor, have impacted their finances. For 22% of respondents, their expenses increased by more than 50%.

IMPACT ON PATIENT VOLUMES

Although volumes did increase over the summer, most of the improvement occurred in areas where it is difficult to delay care, such as oncology and cardiology. For example, oncology was the only field where more than half of respondents (60%) saw their volumes recover to more than 90% of pre-pandemic levels.

More than 40% of respondents said that cardiology volumes are operating at more than 90% of pre-pandemic levels. Only 37% of respondents can say the same for orthopedics, neurology and radiology, and 22% for pediatrics.

Emergency department usage is also down as a result of the pandemic, according to the report. The respondents expect that this trend will persist beyond COVID-19 and that systems may need to reshape their business model to account for a drop in emergency department utilization.

Most respondents also said they expect to see overall volumes remain low through the summer of 2021, with some planning for suppressed volumes for the next three years.

RECOVERY MEASURES

Hospitals and health systems have taken a number of approaches to reduce costs and mitigate future revenue declines. The most common practices implemented are supply reprocessing, furloughs and salary reductions, according to the report.

Executives are considering other tactics such as restructuring physician contracts, making permanent labor reductions, changing employee health plan benefits and retirement plan contributions, or merging with another health system as additional cost reduction measures.

THE LARGER TREND

Kaufman Hall has been documenting the impact of COVID-19 hospitals since the beginning of the pandemic. In its July report, hospital operating margins were down 96% since the start of the year.

As a result of these losses, hospitals, health systems and advocacy groups continue to push Congress to deliver another round of relief measures.

Earlier this month, the House passed a $2.2 trillion stimulus bill called the HEROES Act, 2.0. The bill has yet to pass the Senate, and the chances of that happening are slim, with Republicans in favor of a much smaller, $500 billion package. Nothing is expected to happen prior to the presidential election.

The Department of Health and Human Services also recently announced the third phase of general distribution for the Provider Relief Fund. Applications are currently open and will close on Friday, November 6.

The number of new unemployment claims jumped last week, the latest sign of the toll the coronavirus pandemic continues to take on the economy.

States across the country processed 898,000 new unemployment claims, up more than 50,000 from the previous week, the largest increase in first-time jobless applications since August.

These numbers marked another unfortunate milestone: The number of unemployment claims has been above the pre-pandemic one-week record of 695,000 for 30 weeks now.

Claims for Pandemic Unemployment Assistance, for gig and self-employed workers, went down, to 373,000 from about 460,000.

And the total number of people on all unemployment programs dropped slightly, to 25.3 million for the last week of September, down from 25.5 million the previous week.

The number of new claims has fallen greatly from its peak in the spring, but economists say they are concerned that the number remains so high.

“No question this report casts doubt on the recovery,” said Andrew Chamberlain, the chief economist at Glassdoor. “This is a sign covid is still dealing heavy blows to the labor market. We’re nowhere near having the virus under control.”

The news comes amid a string of poor economic news, with headlines punctuated with reports of large companies announcing layoffs in recent weeks.

These companies include Disney, insurance company Allstate, American and United Airlines, Aetna, and Chevron.

“It’s not coming down quickly,” said Julia Pollak, a labor economist at the jobs site ZipRecruiter. “It’s unclear how quickly we can recover. We’re likely to see additional layoffs and high numbers of unemployment for the foreseeable future.”

Pollak said there are indications that consumer spending has fallen since the expiration of government aid programs — another warning sign about more economic trouble ahead.

Many economists, including those at the Federal Reserve, have urged Congress and the White House to pass a new package of aid. House Democrats passed a $2.2 trillion plan earlier this month that Republicans have declined to advance, while Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin has been pushing a $1.8 trillion plan.

Still, there are signs that Senate Republicans would not be willing to accept that plan, either. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell told reporters that he would not bring the plan to the floor, saying Senate Republicans believed the deal should top out at $1.5 trillion.

One sign of the severity of the economic crisis is the growing number of people who are transitioning to Pandemic Emergency unemployment compensation — for those who hit the maximum number of time that their state plans allow for. That number grew 818,000, according to the most recent figures, from the end of September.

Questions remain about the integrity of the data, as well.

A number of issues have complicated a straightforward read of the weekly release, such as issues with fraud, which are believed to have driven up these numbers an unknown amount, and backlogs in states like California. The country’s largest state typically accounts for about 20-28 percent of the country’s total weekly claims, but has put its claims processing on hold temporarily.

Instead, the Department of Labor is using a placeholder number for the state — 226,000, the number of new initial claims in the state from mid-September.

But some economists like Chamberlain are critical of this method.

“The idea of cutting and pasting the data from a state is so absurd,” he said. “They could at least use a model. But instead they’re carrying over the number. It’s quite a crisis.”

Quirks in the new filing process require people to apply for traditional unemployment and get rejected before applying for PUA — a source of potential duplicate claims.

Economists have been warning for months that the unemployment rate, which has improved steadily since its nadir in April, is at risk of getting worse without further government intervention.

States that saw significant jumps in unemployment claims last week include Indiana, Alaska, Arizona, Illinois, New Mexico and Washington.

Still, some economists have found reasons to hope. Pollak said job postings on ZipRecruiter have topped 10 million for the first time since the start of the pandemic, equaling a number last seen in January.

The jobs are different now, she said — fewer tech and business jobs and more warehousing jobs, temporary opportunities and contracting work.

The financial challenges caused by the COVID-19 pandemic have forced hundreds of hospitals across the nation to furlough, lay off or reduce pay for workers, and others have had to scale back services or close.

Lower patient volumes, canceled elective procedures and higher expenses tied to the pandemic have created a cash crunch for hospitals. U.S. hospitals are estimated to lose more than $323 billion this year, according to a report from the American Hospital Association. The total includes $120.5 billion in financial losses the AHA predicts hospitals will see from July to December.

Hospitals are taking a number of steps to offset financial damage. Executives, clinicians and other staff are taking pay cuts, capital projects are being put on hold, and some employees are losing their jobs. More than 260 hospitals and health systems furloughed workers this year and dozens others have implemented layoffs.

Below are eight hospitals and health systems that announced layoffs since Sept. 1, most of which were attributed to financial strain caused by the pandemic.

1. Citing a need to offset financial losses, Minneapolis-based M Health Fairview said it plans to downsize its hospital and clinic operations. As a result of the changes, 900 employees, about 3 percent of its 34,000-person workforce, will be laid off.

2. Lake Charles (La.) Memorial Health System laid off 205 workers, or about 8 percent of its workforce, as a result of damage sustained from Hurricane Laura. The health system laid off employees at Moss Memorial Health Clinic and the Archer Institute, two facilities in Lake Charles that sustained damage from the hurricane.

3. Burlington, Mass.-based Wellforce laid off 232 employees as a result of operating losses linked to the COVID-19 pandemic. The health system, comprised of Tufts Medical Center, Lowell General Hospital and MelroseWakefield Healthcare, experienced a drastic drop in patient volume earlier this year due to the suspension of outpatient visits and elective surgeries. In the nine months ended June 30, the health system reported a $32.2 million operating loss.

4. Baptist Health Floyd in New Albany, Ind., part of Louisville, Ky.-based Baptist Health, eliminated 36 positions. The hospital said the cuts, which primarily affected administrative and nonclinical roles, are due to restructuring that is “necessary to meet financial challenges compounded by COVID-19.”

5. Cincinnati-based UC Health laid off about 100 employees. The job cuts affected both clinical and non-clinical staff. A spokesperson for the health system said no physicians were laid off.

6. Mercy Iowa City (Iowa) announced in September that it will lay off 29 employees to address financial strain tied to the COVID-19 pandemic.

7. Springfield, Ill.-based Memorial Health System laid off 143 employees, or about 1.5 percent of the five-hospital system’s workforce. The health system cited financial pressures tied to the pandemic as the reason for the layoffs.

8. Watertown, N.Y.-based Samaritan Health announced Sept. 8 that it laid off 51 employees and will make other cost-cutting moves to offset financial stress tied to the COVID-19 pandemic.