America was not prepared for COVID-19 when it arrived. It was not prepared for last winter’s surge. It was not prepared for Delta’s arrival in the summer or its current winter assault. More than 1,000 Americans are still dying of COVID every day, and more have died this year than last. Hospitalizations are rising in 42 states. The University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha, which entered the pandemic as arguably the best-prepared hospital in the country, recently went from 70 COVID patients to 110 in four days, leaving its staff “grasping for resolve,” the virologist John Lowe told me. And now comes Omicron.

Will the new and rapidly spreading variant overwhelm the U.S. health-care system? The question is moot because the system is already overwhelmed, in a way that is affecting all patients, COVID or otherwise. “The level of care that we’ve come to expect in our hospitals no longer exists,” Lowe said.

The real unknown is what an Omicron cross will do when it follows a Delta hook. Given what scientists have learned in the three weeks since Omicron’s discovery, “some of the absolute worst-case scenarios that were possible when we saw its genome are off the table, but so are some of the most hopeful scenarios,” Dylan Morris, an evolutionary biologist at UCLA, told me. In any case, America is not prepared for Omicron. The variant’s threat is far greater at the societal level than at the personal one, and policy makers have already cut themselves off from the tools needed to protect the populations they serve. Like the variants that preceded it, Omicron requires individuals to think and act for the collective good—which is to say, it poses a heightened version of the same challenge that the U.S. has failed for two straight years, in bipartisan fashion.

The coronavirus is a microscopic ball studded with specially shaped spikes that it uses to recognize and infect our cells. Antibodies can thwart such infections by glomming onto the spikes, like gum messing up a key. But Omicron has a crucial advantage: 30-plus mutations that change the shape of its spike and disable many antibodies that would have stuck to other variants. One early study suggests that antibodies in vaccinated people are about 40 times worse at neutralizing Omicron than the original virus, and the experts I talked with expect that, as more data arrive, that number will stay in the same range. The implications of that decline are still uncertain, but three simple principles should likely hold.

First, the bad news: In terms of catching the virus, everyone should assume that they are less protected than they were two months ago. As a crude shorthand, assume that Omicron negates one previous immunizing event—either an infection or a vaccine dose. Someone who considered themselves fully vaccinated in September would be just partially vaccinated now (and the official definition may change imminently). But someone who’s been boosted has the same ballpark level of protection against Omicron infection as a vaccinated-but-unboosted person did against Delta. The extra dose not only raises a recipient’s level of antibodies but also broadens their range, giving them better odds of recognizing the shape of even Omicron’s altered spike. In a small British study, a booster effectively doubled the level of protection that two Pfizer doses provided against Omicron infection.

Second, some worse news: Boosting isn’t a foolproof shield against Omicron. In South Africa, the variant managed to infect a cluster of seven people who were all boosted. And according to a CDC report, boosted Americans made up a third of the first known Omicron cases in the U.S. “People who thought that they wouldn’t have to worry about infection this winter if they had their booster do still have to worry about infection with Omicron,” Trevor Bedford, a virologist at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, told me. “I’ve been going to restaurants and movies, and now with Omicron, that will change.”

Third, some better news: Even if Omicron has an easier time infecting vaccinated individuals, it should still have more trouble causing severe disease. The vaccines were always intended to disconnect infection from dangerous illness, turning a life-threatening event into something closer to a cold. Whether they’ll fulfill that promise for Omicron is a major uncertainty, but we can reasonably expect that they will. The variant might sneak past the initial antibody blockade, but slower-acting branches of the immune system (such as T cells) should eventually mobilize to clear it before it wreaks too much havoc.

To see how these principles play out in practice, Dylan Morris suggests watching highly boosted places, such as Israel, and countries where severe epidemics and successful vaccination campaigns have given people layers of immunity, such as Brazil and Chile. In the meantime, it’s reasonable to treat Omicron as a setback but not a catastrophe for most vaccinated people. It will evade some of our hard-won immune defenses, without obliterating them entirely. “It was better than I expected, given the mutational profile,” Alex Sigal of the Africa Health Research Institute, who led the South African antibody study, told me. “It’s not going to be a common cold, but neither do I think it will be a tremendous monster.”

That’s for individuals, though. At a societal level, the outlook is bleaker.

Omicron’s main threat is its shocking speed, as my colleague Sarah Zhang has reported. In South Africa, every infected person has been passing the virus on to 3–3.5 other people—at least twice the pace at which Delta spread in the summer. Similarly, British data suggest that Omicron is twice as good at spreading within households as Delta. That might be because the new variant is inherently more transmissible than its predecessors, or because it is specifically better at moving through vaccinated populations. Either way, it has already overtaken Delta as the dominant variant in South Africa. Soon, it will likely do the same in Scotland and Denmark. Even the U.S., which has much poorer genomic surveillance than those other countries, has detected Omicron in 35 states. “I think that a large Omicron wave is baked in,” Bedford told me. “That’s going to happen.”

More positively, Omicron cases have thus far been relatively mild. This pattern has fueled the widespread claim that the variant might be less severe, or even that its rapid spread could be a welcome development. “People are saying ‘Let it rip’ and ‘It’ll help us build more immunity,’ that this is the exit wave and everything’s going to be fine and rosy after,” Richard Lessells, an infectious-disease physician at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, in South Africa, told me. “I have no confidence in that.”

To begin with, as he and others told me, that argument overlooks a key dynamic: Omicron might not actually be intrinsically milder. In South Africa and the United Kingdom, it has mostly infected younger people, whose bouts of COVID-19 tend to be less severe. And in places with lots of prior immunity, it might have caused few hospitalizations or deaths simply because it has mostly infected hosts with some protection, as Natalie Dean, a biostatistician at Emory University, explained in a Twitter thread. That pattern could change once it reaches more vulnerable communities. (The widespread notion that viruses naturally evolve to become less virulent is mistaken, as the virologist Andrew Pekosz of Johns Hopkins University clarified in The New York Times.) Also, deaths and hospitalizations are not the only fates that matter. Supposedly “mild” bouts of COVID-19 have led to cases of long COVID, in which people struggle with debilitating symptoms for months (or even years), while struggling to get care or disability benefits.

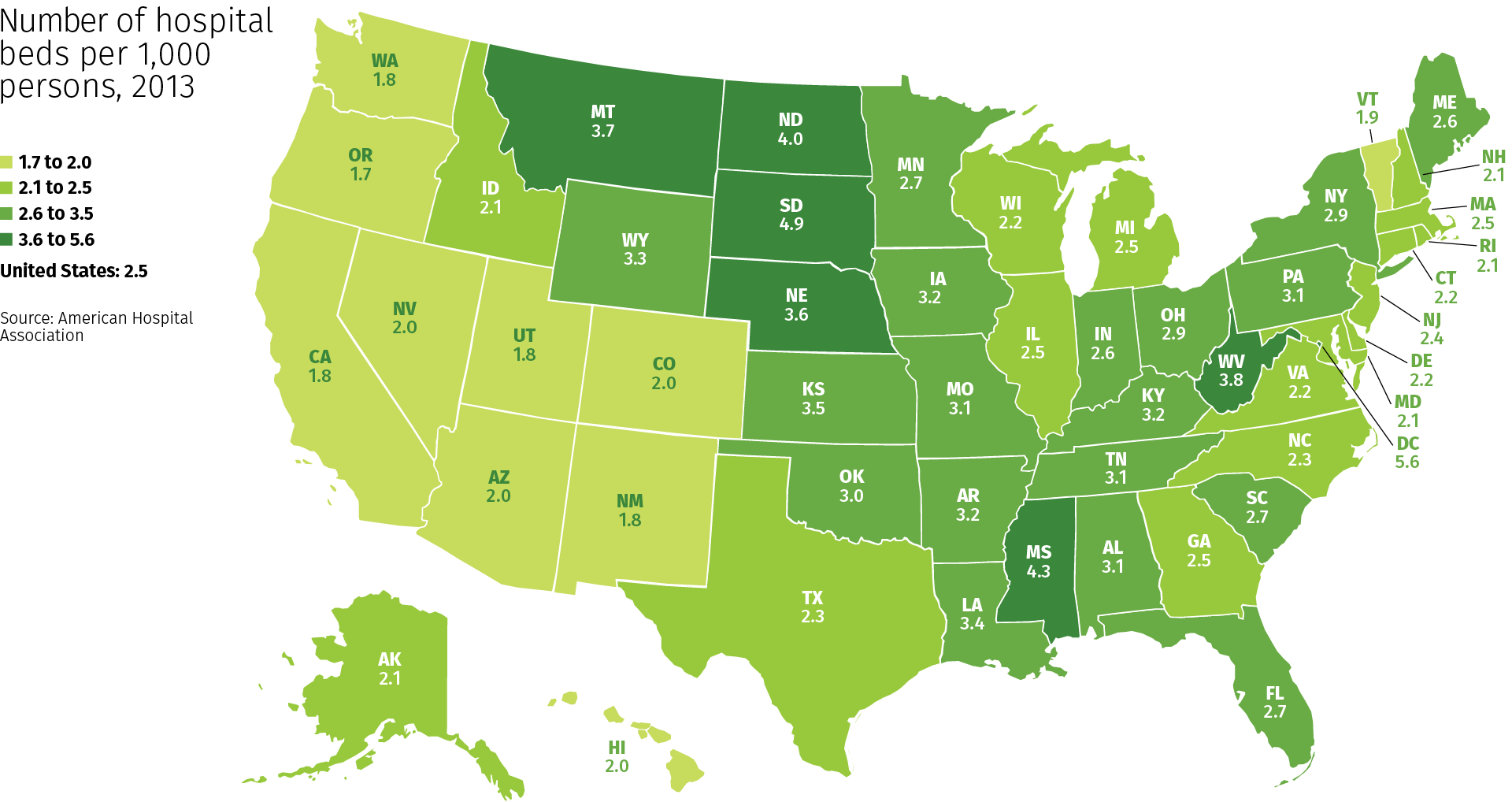

And even if Omicron is milder, greater transmissibility will likely trump that reduced virulence. Omicron is spreading so quickly that a small proportion of severe cases could still flood hospitals. To avert that scenario, the variant would need to be substantially milder than Delta—especially because hospitals are already at a breaking point. Two years of trauma have pushed droves of health-care workers, including many of the most experienced and committed, to quit their job. The remaining staff is ever more exhausted and demoralized, and “exceptionally high numbers” can’t work because they got breakthrough Delta infections and had to be separated from vulnerable patients, John Lowe told me. This pattern will only worsen as Omicron spreads, if the large clusters among South African health-care workers are any indication. “In the West, we’ve painted ourselves into a corner because most countries have huge Delta waves and most of them are stretched to the limit of their health-care systems,” Emma Hodcroft, an epidemiologist at the University of Bern, in Switzerland, told me. “What happens if those waves get even bigger with Omicron?”

The Omicron wave won’t completely topple America’s wall of immunity but will seep into its many cracks and weaknesses. It will find the 39 percent of Americans who are still not fully vaccinated (including 28 percent of adults and 13 percent of over-65s). It will find other biologically vulnerable people, including elderly and immunocompromised individuals whose immune systems weren’t sufficiently girded by the vaccines. It will find the socially vulnerable people who face repeated exposures, either because their “essential” jobs leave them with no choice or because they live in epidemic-prone settings, such as prisons and nursing homes. Omicron is poised to speedily recap all the inequities that the U.S. has experienced in the pandemic thus far.

Here, then, is the problem: People who are unlikely to be hospitalized by Omicron might still feel reasonably protected, but they can spread the virus to those who are more vulnerable, quickly enough to seriously batter an already collapsing health-care system that will then struggle to care for anyone—vaccinated, boosted, or otherwise. The collective threat is substantially greater than the individual one. And the U.S. is ill-poised to meet it.

America’s policy choices have left it with few tangible options for averting an Omicron wave. Boosters can still offer decent protection against infection, but just 17 percent of Americans have had those shots. Many are now struggling to make appointments, and people from rural, low-income, and minority communities will likely experience the greatest delays, “mirroring the inequities we saw with the first two shots,” Arrianna Marie Planey, a medical geographer at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, told me. With a little time, the mRNA vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna could be updated, but “my suspicion is that once we have an Omicron-specific booster, the wave will be past,” Trevor Bedford, the virologist, said.

Two antiviral drugs now exist that could effectively keep people out of the hospital, but neither has been authorized and both are expensive. Both must also be administered within five days of the first symptoms, which means that people need to realize they’re sick and swiftly confirm as much with a test. But instead of distributing rapid tests en masse, the Biden administration opted to merely make them reimbursable through health insurance. “That doesn’t address the need where it is greatest,” Planey told me. Low-wage workers, who face high risk of infection, “are the least able to afford tests up front and the least likely to have insurance,” she said. And testing, rapid or otherwise, is about to get harder, as Omicron’s global spread strains both the supply of reagents and the capacity of laboratories.

Omicron may also be especially difficult to catch before it spreads to others, because its incubation period—the window between infection and symptoms—seems to be very short. At an Oslo Christmas party, almost three-quarters of attendees were infected even though all reported a negative test result one to three days before. That will make Omicron “harder to contain,” Lowe told me. “It’s really going to put a lot of pressure on the prevention measures that are still in place—or rather, the complete lack of prevention that’s still in place.”

The various measures that controlled the spread of other variants—masks, better ventilation, contact tracing, quarantine, and restrictions on gatherings—should all theoretically work for Omicron too. But the U.S. has either failed to invest in these tools or has actively made it harder to use them. Republican legislators in at least 26 states have passed laws that curtail the very possibility of quarantines and mask mandates. In September, Alexandra Phelan of Georgetown University told me that when the next variant comes, such measures could create “the worst of all worlds” by “removing emergency actions, without the preventive care that would allow people to protect their own health.” Omicron will test her prediction in the coming weeks.

The longer-term future is uncertain. After Delta’s emergence, it became clear that the coronavirus was too transmissible to fully eradicate. Omicron could potentially shunt us more quickly toward a different endgame—endemicity, the point when humanity has gained enough immunity to hold the virus in a tenuous stalemate—albeit at significant cost. But more complicated futures are also plausible. For example, if Omicron and Delta are so different that each can escape the immunity that the other induces, the two variants could co-circulate. (That’s what happened with the viruses behind polio and influenza B.)

Omicron also reminds us that more variants can still arise—and stranger ones than we might expect. Most scientists I talked with figured the next one to emerge would be a descendant of Delta, featuring a few more mutational bells and whistles. Omicron, however, is “dramatically different,” Shane Crotty, from the La Jolla Institute for Immunology, told me. “It showed a lot more evolutionary potential than I or others had hoped for.” It evolved not from Delta but from older lineages of SARS-CoV-2, and seems to have acquired its smorgasbord of mutations in some hidden setting: perhaps a part of the world that does very little sequencing, or an animal species that was infected by humans and then transmitted the virus back to us, or the body of an immunocompromised patient who was chronically infected with the virus. All of these options are possible, but the people I spoke with felt that the third—the chronically ill patient—was most likely. And if that’s the case, with millions of immunocompromised people in the U.S. alone, many of whom feel overlooked in the vaccine era, will more weird variants keep arising? Omicron “doesn’t look like the end of it,” Crotty told me. One cause for concern: For all the mutations in Omicron’s spike, it actually has fewer mutations in the rest of its proteins than Delta did. The virus might still have many new forms to take.

Vaccinating the world can curtail those possibilities, and is now an even greater matter of moral urgency, given Omicron’s speed. And yet, people in rich countries are getting their booster six times faster than those in low-income countries are getting their first shot. Unless the former seriously commits to vaccinating the world—not just donating doses, but allowing other countries to manufacture and disseminate their own supplies—“it’s going to be a very expensive wild-goose chase until the next variant,” Planey said.

Vaccines can’t be the only strategy, either. The rest of the pandemic playbook remains unchanged and necessary: paid sick leave and other policies that protect essential workers, better masks, improved ventilation, rapid tests, places where sick people can easily isolate, social distancing, a stronger public-health system, and ways of retaining the frayed health-care workforce. The U.S. has consistently dropped the ball on many of these, betting that vaccines alone could get us out of the pandemic. Rather than trying to beat the coronavirus one booster at a time, the country needs to do what it has always needed to do—build systems and enact policies that protect the health of entire communities, especially the most vulnerable ones.

Individualism couldn’t beat Delta, it won’t beat Omicron, and it won’t beat the rest of the Greek alphabet to come.

Self-interest is self-defeating, and as long as its hosts ignore that lesson, the virus will keep teaching it.