Category Archives: Pricing

How can health systems compete in the ambulatory pricing arena?

https://mailchi.mp/c9e26ad7702a/the-weekly-gist-april-7-2023?e=d1e747d2d8

As the locus of care continues to shift from inpatient hospitals to outpatient centers, health system executives face a growing conundrum over pricing. The combination of “consumerism” and tougher reimbursement policies raises a question about how aggressively systems should discount services to compete in the ambulatory arena.

Site-neutral payment remains a goal for Medicare, and consumers are increasingly voting with their pocketbooks when it comes to choosing where to have procedures and diagnostics performed. “We know we’re going to have to give on price,” one CEO recently shared with us. “The question is how much, and how soon.”

Should hospitals proactively shift to match prices offered by freestanding centers, or should they try to defend their substantially higher “hospital outpatient department” (HOPD) pricing?

The former choice could help win—or at least keep—business in the system, but at the risk of turning that business into a money-losing proposition.

To compete successfully, hospitals will not only need to lower price, but also lower cost-to-serve—rethinking how operations are run, how overhead is allocated, and how services are staffed and delivered in ambulatory settings.

“We’ve got to get our costs down,” the CEO admitted. “Trying to run an ambulatory business with our traditional hospital cost structure is a recipe for losing money.”

And as a system CFO recently told us, “We can’t just trade good price for bad, for doing the same work. We have to be smart about where to discount services.” The future sustainability of many health systems will hinge on how they navigate this transition to an ambulatory-centric model.

RAND: Private plans paid hospitals 224% more than Medicare rates

Private insurance plans paid hospitals on average 224% more compared with Medicare rates for both inpatient and outpatient services in 2020, a new study found.

Researchers at RAND Corporation looked at data from 4,000 hospitals in 49 states from 2018 to 2020. While the 224% increase in rates is high, it is a slight reduction from the 247% reported in 2018 in the last study RAND performed.

“This reduction is a result of a substantial increase in the volume of claims in the analysis from states with prices below the previous average price,” the study said.

The report showed that plans in certain states wound up paying hospitals more than others. It found that Florida, West Virginia and South Carolina had prices that were at or even higher than 310% of Medicare.

But other states like Hawaii, Arkansas and Washington paid less than 175% of Medicare rates.

“Employers can use this report to become better-informed purchasers of health benefits,” study lead author Christopher Waley said in a statement. “The work also highlights the levels and variation in hospital prices paid by employers and private insurers, and thus may help policymakers who may be looking for strategies to curb healthcare spending.”

The data come as the federal government has explored ways to lower healthcare costs, including going toe-to-toe with the hospital industry. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has in recent years sought to cut payments to off-campus outpatient clinics in order to bring Medicare payments in line with payments paid to physicians’ offices but has met with stiff legal and lobbying opposition from the hospital industry that argues the extra payments are needed.

CMS has also published regulations that call on hospitals to increase transparency of prices, including a rule that mandates hospitals publish online the prices for roughly 300 shoppable services.

The hospital industry pushed back against RAND’s findings, arguing that the study is based on incomplete data. The industry group American Hospital Association said researchers only looked at 2.2% of overall hospital spending, a small portion of overall expenses.

“Researchers should expect variation in the cost of delivering services across the wide range of U.S. hospitals – from rural critical access hospitals to large academic medical centers,” said AHA CEO Rick Pollack in a statement to Fierce Healthcare. “Tellingly, when RAND added more claims as compared to previous versions of this report, the average price for hospital services declined.”

Hospital mergers and acquisitions are a bad deal for patients. Why aren’t they being stopped?

Contrary to what health care executives advertise, hospital mergers and acquisitions aren’t good for patients. They rarely improve access to health care or its quality, and they don’t reduce prices. But the system in place to stop them is often more bark than bite.

During 2019 and 2020, hospitals acquired an additional 3,200 medical practices and 18,600 physicians. By January 2021, almost half of all U.S. physicians were employed by a hospital or health system.

In 2018, the last year for which complete data are available, 72% of hospitals and more than 90% of hospital beds were affiliated with a health care system. Mergers and acquisitions are increasing the number of health care systems while decreasing the number of independently operated hospitals.

When hospitals buy provider practices, it leads to more unnecessary care and more expensive care, which increases overall spending. The same thing happens when hospitals merge or acquire other hospitals. These deals often increase prices and they don’t improve care quality; patients simply pay more for the same or worse care.

Mergers and acquisitions can negatively affect clinician morale as well. Some argue they lead to providers’ loss of autonomy and increase the emphasis on financial targets rather than patient care. They can also contribute to burnout and feeling unsupported.

Considerable machinery is in place at both the federal and state levels to stop “anticompetitive” mergers before they happen. But that machinery is limited by a lack of follow through.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the U.S. Department of Justice have always had broad authority over mergers. By law, one or both of these entities must review for any antitrust concerns proposed deals of a certain size before the deals are finalized. After a preliminary review, if no competition issues are identified, the merger or acquisition is allowed to proceed. This is what happens in most cases. If concerns are raised, however, the involved parties must submit additional information and undergo a second evaluation.

Some health care organizations seem willing to challenge this process. Leaders involved in a pending merger between Lifespan and Care New England in Rhode Island — which would leave 80% of the state’s inpatient market under one company’s umbrella — are preparing to move forward even if the FTC deems the deal anticompetitive. The companies will simply ask the state to approve the merger despite the FTC’s concerns.

The reality is that the FTC’s reach is limited when it comes to nonprofits, which most hospitals are. While the FTC can oppose anticompetitive mergers involving nonprofits, it cannot enforce action against them for anticompetitive behavior. So if a merger goes through, the FTC has limited authority to ensure the new entity plays fairly.

What’s more, the FTC has acknowledged it can’t keep up with its workload this year. It modified its antitrust review process to accommodate an increasing number of requests and its stagnant capacity. In July, the Biden administration issued an executive order about economic competition that explicitly acknowledges the negative impact of health care consolidation on U.S. communities. This is encouraging, signaling that the government is taking mergers seriously. Yet it’s unclear if the executive order will give the FTC more capacity, which is essential if it is to actually enforce antitrust laws.

At the state level, most of the antitrust power lies with the attorney general, who ultimately approves or challenges all mergers. Despite this authority, questionable mergers still go through.

In 2018, for example, two competing hospital systems in rural Tennessee merged to become Ballad Health and the only source of care for about 1.2 million residents. The deal was opposed by the FTC, which deemed it to be a monopoly. Despite the concerns, the state attorney general and Department of Health overrode the FTC’s ruling and approved the merger. (This is the same mechanism the Rhode Island hospitals hope to employ should the FTC oppose their merger.) As expected, Ballad Health then consolidated the services offered at its facilities and increased the fees on patient bills.

It’s clear that mechanisms exist to curb potentially harmful mergers and promote industry competition. It’s also clear they aren’t being used to the fullest extent. Unless these checks and balances lead to mergers being denied, their power over the market is limited.

Experts have been raising the alarm on health care consolidation for years. Mergers rarely lead to better care quality, access, or prices. Proposed mergers must be assessed and approved based on evidence, not industry pressure. If nothing changes, the consequences will be felt for years to come.

Why this insurance CEO thinks big healthcare brands are losing significance

Legacy health brands are losing their significance as healthcare consumers place higher value on convenience than reputation. That’s the idea behind a July 1 tweet by Sachin Jain, MD, the CEO of Scan Group and Scan Health Plan.

“We are in an era of the declining significance of big healthcare brands,” he said.

To Dr. Jain, big healthcare brands are the ones commonly known for being the best in a specific specialty or renowned in their region. While many big healthcare brands have high quality performance metrics to hang their clout on, Dr. Jain believes reliance on name alone is problematic.

“There’s been an arrogance by a lot of healthcare organizations that have kind of sold on brand. There’s going to be a reckoning for some of those organizations. My personal view is that the next generation of healthcare consumers is going to be less aligned to think about brands in the same way,” Dr. Jain told Becker’s.

Today’s patients are paying more attention to convenience, digital access and price than reputation. Cost of care, ease of scheduling and accessibility are beating out recognition, Dr. Jain said.

At Scan, Dr. Jain said the Long Beach, Calif.-based Medicare Advantage insurer that serves more than 220,000 members is hyperfocused on staying as human as possible and fulfilling unmet needs for its community.

“Elite healthcare brands are entering this fun phase where they are becoming underdogs. They need to have a chip on their shoulders almost to thrive and perform in this next phase,” Dr. Jain said. “Because I’m not sure payers are necessarily going to continue to pay the same premiums per brand.”

Georgia health systems discard merger plans, averting FTC challenge

/the-us-federal-trade-commission--ftc--bu-71968930-e5e36febe53543aaa53329c6c17fc982.jpg)

Dive Brief:

- The Federal Trade Commission has closed its investigation of the merger between Atrium Health Navicent and Houston Healthcare System following news the two have abandoned their plans for a deal.

- FTC staff had recommended commissioners challenge the merger on grounds that it would have led to “significant harm” for area residents and businesses in the form of higher healthcare costs, the FTC alleged.

- The tie-up between two of the largest systems in central Georgia would also hamper investment in facilities, technologies and expanded access to services, according to a statement released Wednesday.

Dive Insight:

FTC Acting Chairwoman Rebecca Kelly Slaughter said in the statement, “This is great news for patients in central Georgia.”

When the deal was originally announced, Atrium Health Navicent promised to spend $150 million on Houston over a decade, earmarking the money for routine capital expenditures and strategic growth initiatives, according to a previous review of the transaction by the state attorney general’s office.

After engaging with consultants at Kaufman Hall in 2017, leaders at Houston, an independent system, decided they needed to find a strategic partner to weather long-term challenges and ultimately picked Navicent.

Navicent recently merged with North Carolina-based Atrium Health, formerly known as Carolinas HealthCare System. At the time, the deal gave Atrium a foothold in the state of Georgia.

Healthcare consolidation has continued at a steady clip despite the pandemic, and the FTC will be closely investigating any deal involving close competitors. The agency is seeking to expand its arsenal to block future mergers by researching new theories of harm.

The FTC attempted to block a hospital deal in Philadelphia last year but has since abandoned its challenge after a series of setbacks in court. The judge was not swayed that the consolidation of providers would lead to an increase in prices given the plethora of healthcare options in the area.

Cartoon – State of the Union (Underinsured)

The High Price of Lowering Health Costs for 150 Million Americans

https://one.npr.org/?sharedMediaId=968920752:968920754

The Problem

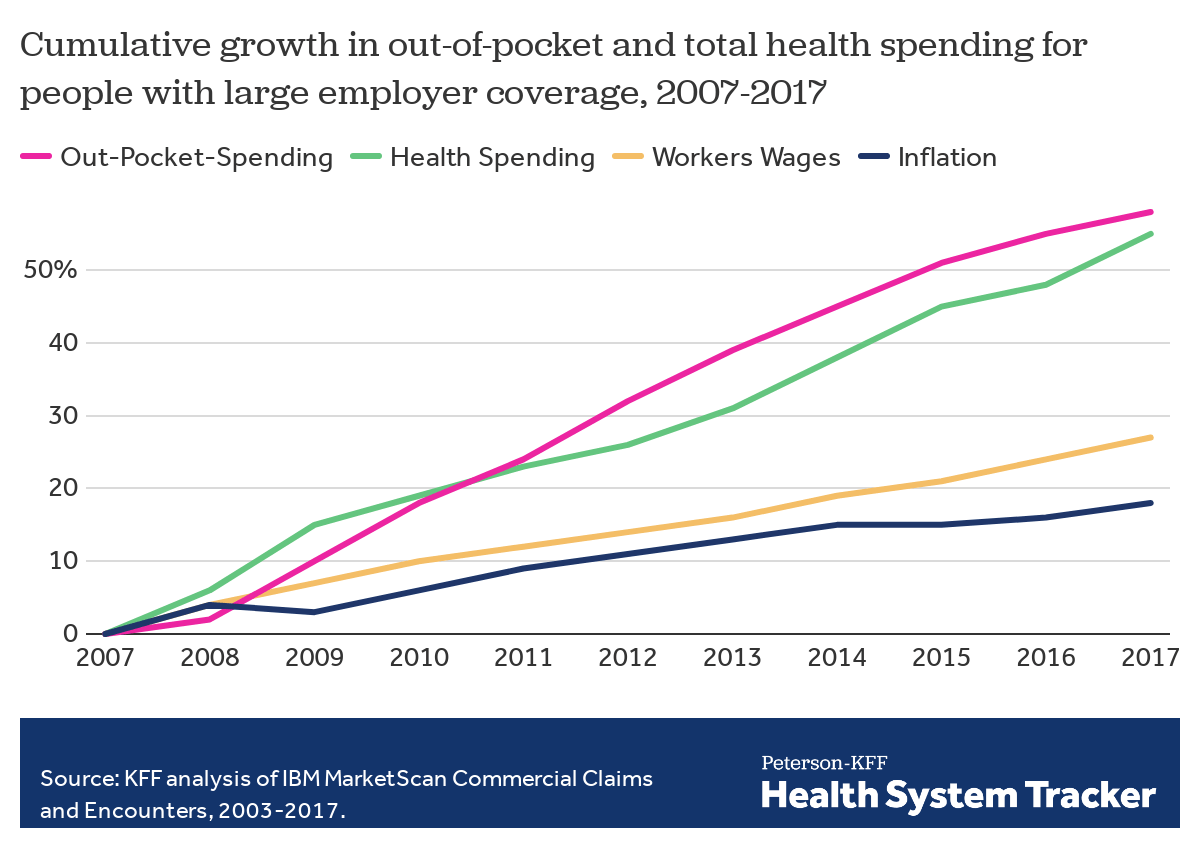

Employers — including companies, state governments and universities — purchase health care on behalf of roughly 150 million Americans. The cost of that care has continued to climb for both businesses and their workers.

For many years, employers saw wasteful care as the primary driver of their rising costs. They made benefits changes like adding wellness programs and raising deductibles to reduce unnecessary care, but costs continued to rise. Now, driven by a combination of new research and changing market forces — especially hospital consolidation — more employers see prices as their primary problem.

The Evidence

The prices employers pay hospitals have risen rapidly over the last decade. Those hospitals provide inpatient care and increasingly, as a result of consolidation, outpatient care too. Together, inpatient and outpatient care account for roughly two-thirds of employers’ total spending per employee.

By amassing and analyzing employers’ claims data in innovative ways, academics and researchers at organizations like the Health Care Cost Institute (HCCI) and RAND have helped illuminate for employers two key truths about the hospital-based health care they purchase:

1) PRICES VARY WIDELY FOR THE SAME SERVICES

Data show that providers charge private payers very different prices for the exact same services — even within the same geographic area.

For example, HCCI found the price of a C-section delivery in the San Francisco Bay Area varies between hospitals by as much as:$24,107

Research also shows that facilities with higher prices do not necessarily provide higher quality care.

2) HOSPITALS CHARGE PRIVATE PAYERS MORE

Data show that hospitals charge employers and private insurers, on average, roughly twice what they charge Medicare for the exact same services. A recent RAND study analyzed more than 3,000 hospitals’ prices and found the most expensive facility in the country charged employers:4.1xMedicare

Hospitals claim this price difference is necessary because public payers like Medicare do not pay enough. However, there is a wide gap between the amount hospitals lose on Medicare (around -9% for inpatient care) and the amount more they charge employers compared to Medicare (200% or more).

Employer Efforts

A small but growing group of companies, public employers (like state governments and universities) and unions is using new data and tactics to tackle these high prices. (Learn more about who’s leading this work, how and why by listening to our full podcast episode in the player above.)

Note that the employers leading this charge tend to be large and self-funded, meaning they shoulder the risk for the insurance they provide employees, giving them extra flexibility and motivation to purchase health care differently. The approaches they are taking include:

Steering Employees

Some employers are implementing so-called tiered networks, where employees pay more if they want to continue seeing certain, more expensive providers. Others are trying to strongly steer employees to particular hospitals, sometimes know as centers of excellence, where employers have made special deals for particular services.

Purdue University, for example, covers travel and lodging and offers a $500 stipend to employees that get hip or knee replacements done at one Indiana hospital.

Negotiating New Deals

There is a movement among some employers to renegotiate hospital deals using Medicare rates as the baseline — since they are transparent and account for hospitals’ unique attributes like location and patient mix — as opposed to negotiating down from charges set by hospitals, which are seen by many as opaque and arbitrary. Other employers are pressuring their insurance carriers to renegotiate the contracts they have with hospitals.

In 2016, the Montana state employee health plan, led by Marilyn Bartlett, got all of the state’s hospitals to agree to a payment rate based on a multiple of Medicare. They saved more than $30 million in just three years. Bartlett is now advising other states trying to follow her playbook.

In 2020, several large Indiana employers urged insurance carrier Anthem to renegotiate their contract with Parkview Health, a hospital system RAND researchers identified as one of the most expensive in the country. After months of tense back-and-forth, the pair reached a five-year deal expected to save Anthem customers $700 million.

Legislating, Regulating, Litigating

Some employer coalitions are advocating for more intervention by policymakers to cap health care prices or at least make them more transparent. States like Colorado and Indiana have passed price transparency legislation, and new federal rules now require more hospital price transparency on a national level. Advocates expect strong industry opposition to stiffer measures, like price caps, which recently failed in the Montana legislature.

Other advocates are calling for more scrutiny by state and federal officials of hospital mergers and other anticompetitive practices. Some employers and unions have even resorted to suing hospitals like Sutter Health in California.

Employer Challenges

Employers face a few key barriers to purchasing health care in different and more efficient ways:

Provider Power

Hospitals tend to have much more market power than individual employers, and that power has grown in recent years, enabling them to raise prices. Even very large employers have geographically dispersed workforces, making it hard to exert much leverage over any given hospital. Some employers have tried forming purchasing coalitions to pool their buying power, but they face tricky organizational dynamics and laws that prohibit collusion.

Sophistication

Employers can attempt to lower prices by renegotiating contracts with hospitals or tailoring provider networks, but the work is complicated and rife with tradeoffs. Few employers are sophisticated enough, for example, to assess a provider’s quality or to structure hospital payments in new ways. Employers looking for insurers to help them have limited options, as that industry has also become highly consolidated.

Employee Blowback

Employers say they primarily provide benefits to recruit and retain happy and healthy employees. Many are reluctant to risk upsetting employees by cutting out expensive providers or redesigning benefits in other ways. A recent KFF survey found just 4% of employers had dropped a hospital in order to cut costs.

The Tradeoffs

Employers play a unique role in the United States health care system, and in the lives of the 150 million Americans who get insurance through work. For years, critics have questioned the wisdom of an employer-based health care system, and massive job losses created by the pandemic have reinforced those doubts for many.

Assuming employers do continue to purchase insurance on behalf of millions of Americans, though, focusing on lowering the prices they pay is one promising path to lowering total costs. However, as noted above, hospitals have expressed concern over the financial pressures they may face under these new deals. Complex benefit design strategies, like narrow or tiered networks, also run the risk of harming employees, who may make suboptimal choices or experience cost surprises. Finally, these strategies do not necessarily address other drivers of high costs including drug prices and wasteful care.

FTC signals nurses’ wages will become important measure in antitrust enforcement

The Federal Trade Commission is revamping a key tool in its arsenal to police competition across a plethora of industries, a development that could have direct implications for future healthcare deals.

In September, the FTC said it was expanding its retrospective merger program to consider new questions and areas of study that the bureau previously has not researched extensively.

One avenue it will zero in on is labor markets, including workers and their wages, and how mergers may ultimately affect them.

It’s an area that could be ripe for scrutinizing healthcare deals, and the FTC has already begun to use this argument to bolster its case against anticompetitive tie-ups. Prior to this new argument, the antitrust agency — in its legal challenges and research — has primarily focused on how healthcare mergers affect prices.

The retrospective program is hugely important to the FTC as it is a way to examine past mergers and produce research that can be used as evidence in legal challenges to block future anticompetitive deals or even challenge already consummated deals.

“I do suspect that healthcare is a significant concern underlying why they decided to expand this program,” Bill Horton, an attorney with Jones Walker LLP, said.

So far this year, the FTC has tried to block two proposed hospital mergers. The agency sued to stop a proposed tie-up in Philadelphia in February between Jefferson Health and Albert Einstein Healthcare Network.

More recently, the FTC is attempting to bar Methodist Le Boneheur in Memphis from buying two local hospitals from Tenet Health in a $350 million deal.

In both cases, the agency alleges the deals will end the robust competition that exists and harm consumers in the form of higher prices, including steeper insurance premiums, and diminished quality of services.

The agency has long leaned on the price argument (and its evidence) to challenge proposed transactions. However, recent actions signal the FTC will include a new argument: depressed wages, particularly those of nurses.

In a letter to Texas regulators in September, the FTC warned that if the state allowed a health system to acquire its only other competitor in rural West Texas, it would lead to limited wage growth among registered nurses as an already consolidated market compresses further.

As part of its arguments, the FTC pointed to a 2020 study that researched the effects on labor market concentration and worker outcomes.

Last year, the agency sent orders to five health insurance companies and two health systems to provide information so it could further study the affect COPAs, or Certificates of Public Advantage, have on price and quality. The FTC also noted it was planning to study the impact on wages.

FTC turned to review after string of defeats

A number of losses in the 1990s led the agency to conduct a hospital merger retrospective, Chris Garmon, a former economist with the FTC, said. Garmon has helped conduct and author retrospective reviews.

Between 1994 and 2000, there were about 900 hospital mergers by the U.S Department of Justice’s count. The bureau lost all seven of the cases they attempted to litigate in that time period, according to the DOJ.

The defendants in those cases succeeded by employing two types of defenses. The nonprofit hospitals would argue they would not charge higher prices because as nonprofits they had the best interests of the community in mind. Second, hospitals tried to argue that their markets were much larger than the FTC’s definition, and that they compete with hospitals many miles away.

Retrospective studies found evidence that undermined these claims. That’s why the studies are so important, Garmon said.

“It really is to better understand what happens after mergers,” Garmon said. It’s an evaluation exercise, given many transaction occur prospectively or before a deal is consummated. So the reviews help the FTC answer questions like: “Did we get it right? Or did we let any mergers we shouldn’t let through?”

Sam’s Club launches $1 telehealth visits for members: 7 details

Sam’s Club partnered with primary care telehealth provider 98point6 to offer members virtual visits.

Seven details:

1. Sam’s Club now offers members access to telehealth visits through a text-based app run by 98point6.

2. Members can purchase a $20 quarterly subscription for the first three months; the regular sign-up fee is $30 per person. After the first three months, members pay $33.50 every three months.

3. The subscription gives members unlimited telehealth visits for $1 per visit. The service has board-certified physicians available 24 hours per day, seven days a week.

4. Members can also subscribe for pediatric care.

5. Physicians can diagnose and treat 400 conditions including cold and flu-like symptoms as well as allergies. They can also monitor chronic conditions including diabetes, depression and anxiety.

6. Members can use the app to obtain prescriptions and lab orders as well.

7. Sam’s Club has around 600 stores in the U.S. and Puerto Rico and millions of members.

“Offering access to telemedicine was on our roadmap in the pre-COVID world, but the current environment expedited the need for this service to be easily accessible, readily available and most of all, affordable,” said John McDowell, vice president of pharmacy operations and divisional merchandise at Sam’s Club. “Through providing access to the 98point6 app in a pilot, we quickly realized that our members were eager to have mobile telehealth options and we wanted to provide this healthcare solution to all of our members as a standalone option.”