Abstract

- Issue: Medical debt negatively affects many Americans, especially people of color, women, and low-income families. Federal and state governments have set some standards to protect patients from medical debt.

- Goal: To evaluate the current landscape of medical debt protections at the federal and state levels and identify where they fall short.

- Methods: Analysis of federal and state laws, as well as discussions with state experts in medical debt law and policy. We focus on laws and regulations governing hospitals and debt collectors.

- Key Findings and Conclusion: Federal medical debt protection standards are vague and rarely enforced. Patient protections at the state level help address key gaps in federal protections. Twenty states have their own financial assistance standards, and 27 have community benefit standards. However, the strength of these standards varies widely. Relatively few states regulate billing and collections practices or limit the legal remedies available to creditors. Only five states have reporting requirements that are robust enough to identify noncompliance with state law and trends of discriminatory practices. Future patient protections could improve access to financial assistance, ensure that nonprofit hospitals are earning their tax exemption, and limit aggressive billing and collections practices.

Introduction

Medical debt, or personal debt incurred from unpaid medical bills, is a leading cause of bankruptcy in the United States. As many as 40 percent of U.S. adults, or about 100 million people, are currently in debt because of medical or dental bills. This debt can take many forms, including:

- past-due payments directly owed to a health care provider

- ongoing payment plans

- money owed to a bank or collections agency that has been assigned or sold the medical debt

- credit card debt from medical bills

- money borrowed from family or friends to pay for medical bills.

This report discusses findings from our review of federal and state laws that regulate hospitals and debt collectors to protect patients from medical debt and its negative consequences. First, we briefly discuss the impact and causes of medical debt. Then, we present federal medical debt protections and discuss gaps in standards as well as enforcement. Then, we provide an overview of what states are doing to:

- strengthen requirements for financial assistance and community benefits

- regulate hospitals’ and debt collectors’ billing and collections activities

- limit home liens, foreclosures, and wage garnishment

- develop reporting systems to ensure all hospitals are adhering to standards and not disproportionately targeting people of color and low-income communities.

(See the appendix for an overview of medical debt protections in all 50 states and the District of Columbia.)

Impact of Medical Debt

More than half of people in medical and dental debt owe less than $2,500, but because most Americans cannot cover even minor emergency expenses, this debt disrupts their lives in serious ways. Fear of incurring medical debt also deters many Americans from seeking medical care. About 60 percent of adults who have incurred medical debt say they have had to cut back on basic necessities like food or clothing, and more than half the adults from low-income households (less than $40,000) report that they have used up their savings to pay for their medical debt.

A significant amount of medical debt is either sold or assigned to third-party debt-collecting agencies, who often engage in aggressive efforts to collect on the debt, creating stress for patients. Both hospitals and debt collectors have won judgments against patients, allowing them to take money directly from a patient’s paycheck or place liens on a patient’s home. In some cases, patients have also lost their homes. Medical debt can also have a negative impact on a patient’s credit score.

Key Terms Related to Medical Debt

- Financial assistance policy: A hospital’s policy to provide free or discounted care to certain eligible patients. Eligibility for financial assistance can depend on income, insurance status, and/or residency status. A hospital may be required by law to have a financial assistance policy, or it may choose to implement one voluntarily. Financial assistance is frequently referred to as “charity care.”

- Bad debt: Patient bills that a hospital has tried to collect on and failed. Typically, hospitals are not supposed to pursue collections for bills that qualify for financial assistance or charity care, so bad debt refers to debt owed by patients ineligible for financial assistance.

- Community benefit requirements: Nonprofit hospitals are required by federal law and some state laws to provide community benefits, such as financial assistance and other investments targeting community need, in exchange for a tax exemption.

- Debt collectors or collections agencies: Entities whose business model primarily relies on collecting unpaid debt. They can either collect on behalf of a hospital (while the hospital still technically holds the debt) or buy the debt from a hospital.

- Sale of medical debt: Hospitals sometimes sell the debt patients owe them to third-party debt buyers, who can be aggressive in seeking repayment of the debt.

- Creditor: A party that is owed the medical debt and often wants to collect on the medical debt. This can be a hospital, a debt collector acting on behalf of a hospital, or a third-party debt buyer.

- Debtor: A patient who owes medical debt over unpaid medical bills.

- Wage garnishment: The ability of a creditor to get a court order that would allow them to deduct a portion of a debtor-patient’s paycheck before it reaches the patient. Federal law limits how much can be withheld from a debtor’s paycheck, and some states exceed this federal protection.

- Placing a lien: A legal claim that a creditor can place on a patient’s home, prohibiting the patient from selling, transferring, or refinancing their home without first paying off the creditor. Most states require creditors to get a court order before placing a lien on a home.

- Foreclosure or forced sale: A creditor can repossess and sell a patient’s home to pay off their medical debt. Often, creditors are required to obtain a court order to do so.

Perhaps what is most troubling is that the burden of medical debt is not borne equally: Black and Hispanic/Latino adults and women are much more likely to incur medical debt. Black adults also tend to be sued more often as a result. Uninsured patients, those from low-income households, adults with disabilities, and young families with children are all at a heightened risk of being saddled with medical debt.

Causes of Medical Debt

Most people — 72 percent, according to one estimate — attribute their medical debt to bills from acute care, such as a single hospital stay or treatment for an accident. Nearly 30 percent of adults who owe medical debt owe it entirely for hospital bills.

Although uninsured patients are more likely to owe medical debt than insured patients, having insurance does not fully shield patients from medical debt and all its consequences. More than 40 percent of insured adults report incurring medical debt, likely because they either had a gap in their coverage or were enrolled in insurance with inadequate coverage. High deductibles and cost sharing can leave many exposed to unexpected medical expenses.

The problem of medical debt is further exacerbated by hospitals charging increasingly high prices for medical care and failing to provide adequate financial assistance to uninsured and underinsured patients with low income.

Key Findings

Federal Medical Debt Protections Have Many Gaps

At the federal level, the tax code, enforced by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), requires nonprofit hospitals to broadly address medical debt. However, these requirements do not extend to for-profit hospitals (which make up about a quarter of U.S. hospitals) and have other limitations.

Further, the IRS does not have a strong track record of enforcing these requirements. In the past 10 years, the IRS has not revoked any hospital’s nonprofit status for noncompliance with these standards.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and the Federal Trade Commission have additional oversight authority over credit reporting and debt collectors. The Fair Credit Reporting Act regulates credit reporting agencies and those that provide information to them (debt collectors and hospitals). Consumers have the right to dispute any incomplete or inaccurate information and remove any outdated, negative information. In some cases, patients can directly sue hospitals or debt collectors for inaccurately reporting medical debt to credit reporting agencies. In addition, the Federal Debt Collection Practices Act limits how aggressive debt collectors can be by restricting the ways and times in which they can contact debtors, requiring certain disclosures and notifications, and prohibiting unfair or deceptive practices. Patients can directly sue debt collectors in violation of the law. This law, however, does not limit or prohibit the use of certain legal remedies, like wage garnishment or foreclosure, to collect on a debt.

Many states have taken steps to fill the gaps in federal standards. Within a state, several agencies may play a role in enforcing medical debt protections. Generally speaking:

- state departments of health are the primary regulators of hospitals and set standards for them

- state departments of taxation are responsible for ensuring nonprofit hospitals are earning their exemption from state taxes

- state attorneys general protect consumers from unfair and deceptive business practices by hospitals and debt collectors.

Fewer Than Half of States Exceed Federal Requirements for Financial Assistance, Protections Vary Widely

Federal law requires nonprofit hospitals to establish and publicize a written financial assistance policy, but these standards leave out for-profit hospitals and lack any minimum eligibility requirements. As the primary regulators of hospitals, states have the ability to fill these gaps and require hospitals to provide financial assistance to low-income residents. Twenty states require hospitals to provide financial assistance and set certain minimum standards that exceed the federal standard.

All but three of these 20 states extend their financial assistance requirements to for-profit hospitals. Of these 20 states, four states — Connecticut, Georgia, Nevada, and New York — apply their financial assistance requirements only to certain types of hospitals.

Policies also vary among the 31 states that do not have statutory or regulatory financial assistance requirements for hospitals. For example, the Minnesota attorney general has an agreement in place with nearly every hospital in the state to adhere to certain patient protections, though it falls short of requiring hospitals to provide financial assistance. Massachusetts operates a state-run financial assistance program partly funded through hospital assessments. Other states use far less prescriptive mechanisms to try to ensure that patients have access to financial assistance, such as placing the onus of treating low-income patients on individual counties or requiring hospitals to have a plan for treating low-income and/or uninsured patients without setting any specific requirements.

Enforcement of state financial assistance standards.

The only way to enforce the federal financial assistance requirement is to threaten a hospital’s nonprofit status, and the IRS has been reluctant to use this authority. Among the 20 states that have their own state financial assistance standards, 10 require compliance as a condition of licensure or as a legal mandate. These mandates are often coupled with administrative penalties, but some states have established additional consequences. For example, Maine allows patients to sue noncompliant hospitals.

Six states make compliance with their financial assistance standards a condition of receiving funding from the state. Two other states use their certificate-of-need process (which requires hospitals to seek the state’s approval before establishing new facilities or expanding an existing facility’s services) to impose their financial assistance mandates.

Setting eligibility requirements for financial assistance.

The federal financial assistance standard sets no minimum eligibility requirements for hospitals to follow. However, the 20 states with financial assistance standards define which residents are eligible for aid.

One way for states to ensure that financial assistance is available to those most in need is to prevent hospitals from discriminating against undocumented immigrants. Four states explicitly prohibit such discrimination in statute and regulation. Most states, however, are less explicit. Thirteen states define eligibility broadly, basing it most frequently on income, insurance status, and state residency. However, it is unclear how hospitals are interpreting this requirement when it comes to patients’ immigration status. In contrast, three states explicitly exclude undocumented immigrants from eligibility.

States also vary widely in terms of which income brackets are eligible for financial assistance and how much financial assistance they may receive.

At least three of the 20 states with financial assistance standards allow certain patients with heavy out-of-pocket medical expenses from catastrophic illness or prior medical debt to access financial assistance. Many states also require hospitals to consider a patient’s insurance status when making financial assistance determinations. At least six states make financial assistance available for uninsured patients only, while at least eight others also make financial assistance available to underinsured patients.

Standardizing the application process.

Cumbersome applications can discourage many patients from applying for financial assistance. Five states have developed a uniform application form, while three others have set minimum standards for financial assistance applications. Eleven states require hospitals to give patients the right to appeal a denial of financial assistance.

States Split in Requiring Nonprofit Hospitals to Invest in Community Benefits

Federal and state policymakers also can require nonprofit hospitals to invest in community benefits in return for tax exemptions. Federal law requires nonprofit hospitals to produce a community health needs assessment every three years and have an implementation strategy. Almost all states exempt nonprofit hospitals from a host of state taxes, including income, property, and/or sales taxes. However, only 27 impose community benefit requirements on nonprofit hospitals.

Community benefits frequently include financial assistance but also investments that address issues like lack of access to food and housing. In the long run, these investments can reduce medical debt burden by improving population health and the financial stability of a community. Most states that require nonprofit hospitals to provide community benefits allow nonprofit hospitals to choose how they invest their community benefit dollars. This hands-off approach has given rise to concerns about the lack of transparency in community benefit spending as well as questions about whether hospitals are investing this money in ways that are most helpful to the community, such as in providing financial assistance.

Applicability of community benefit standards.

Nineteen states impose community benefit requirements on all nonprofit hospitals in the state, but three states further limit these requirements to hospitals of a certain size. At least six states have extended these requirements to for-profit hospitals as well. Of these six, the District of Columbia, South Carolina, and Virginia have incorporated community benefit requirements into their certificate-of-need laws instead of their tax laws. As a result, any hospital seeking to expand in these states becomes subject to their community benefit requirement.

Interaction between financial assistance and community benefits.

The federal standard allows nonprofit hospitals to report financial assistance as part of their community benefit spending. Most states with community benefit requirements also allow hospitals to do this. However, only seven states require hospitals to provide financial assistance to satisfy their community benefit obligations.

Setting quantitative standards for community benefit spending.

Only seven states set minimum spending thresholds that hospitals must meet or exceed to satisfy state community benefit standards. For example, Illinois and Utah require nonprofit hospitals’ community benefit contributions to equal what their property tax liability would have been. Unique among states, Pennsylvania gives taxing districts the right to sue nonprofit hospitals for not holding up their end of the bargain, which has proven to be a strong enforcement mechanism.

Fewer Than Half the States Exceed Federal Standards for Billing and Collections

Hospital billing and collections practices can significantly increase the burden of medical debt on patients. However, the current federal standard does not regulate these practices beyond imposing waiting periods and prior notification requirements for certain extraordinary collections actions (ECAs), such as garnishing wages or selling the debt to a third party.

Requiring hospitals to provide payment plans.

Federal standards do not require hospitals to make payment plans available. However, a few states do require hospitals to offer payment plans, particularly for low-income and/or uninsured patients. For example, Colorado requires hospitals to provide a payment plan and limit monthly payments to 4 percent of a patient’s monthly gross income and to discharge the debt once the patient has made 36 payments.

Limiting interest on medical debt.

Federal law does not limit the amount of interest that can be charged on medical debt. However, eight states have laws prohibiting or limiting interest for medical debt. Some states like Arizona have set a ceiling for interest on all medical debt. Others like Connecticut further prohibit charging interest to patients who are at or below 250 percent of the federal poverty level and are ineligible for public insurance programs.

Though many states do not have specific laws prohibiting or limiting interest that hospitals or debt collectors can charge on medical debt, all states do have usury laws, which limit the amount of interest than can be charged on any oral or written agreement. Usury limits are set state-by-state and can range anywhere from 5 percent to more than 20 percent, but most limits fall well below the average interest rate for a credit card (around 24%). At least one state, Minnesota, has sued a health system for charging interest rates on medical debt that exceeded the allowed limit in the state’s usury laws.

Interactions between hospitals, third-party debt collectors, and patients.

Unlike hospitals, debt collectors do not have a relationship with patients and can be more aggressive when collecting on the debt. Federal law neither limits when a hospital can send a bill to collections, nor does it require hospitals to oversee the debt collectors it uses. Most states (37) also do not regulate when a hospital can send a bill to collections, although some states have developed more protective approaches.

For example, Connecticut prohibits hospitals from sending the bills of certain low-income patients to collections, and Illinois requires hospitals to offer a reasonable payment plan first. Additionally, five states require hospitals to oversee their debt collectors.

Sale of medical debt to third-party debt buyers.

Hospitals sometimes sell old unpaid debt to third-party debt buyers for pennies on the dollar. Debt buyers can be aggressive in their efforts to collect, and sometimes even try to collect on debt that was never owed. Federal law considers the sale of medical debt an ECA and requires nonprofit hospitals to follow certain notice and waiting requirements before initiating the sale. Most states (44) do not exceed this federal standard.

Only three states prohibit the sale of medical debt. Two other states — California and Colorado — regulate debt buyers instead. For example, California prohibits debt buyers from charging interest or fees, and Colorado prohibits them from foreclosing on a patient’s home.

Reporting medical debt to credit reporting agencies.

Federal law considers reporting medical debt to a credit reporting agency to be an ECA and requires nonprofit hospitals to follow certain notice and waiting requirements beforehand. Most states (41) do not exceed this federal standard.

Of the 10 states that do go beyond the federal standard, a few like Minnesota fully prohibit hospitals from reporting medical debt. Most others require hospitals, debt collectors, and/or debt buyers to wait a certain amount of time before reporting the debt to credit agencies (Exhibit 8). Two states directly regulate credit agencies: Colorado prohibits them from reporting on any medical debt under $726,200, while Maine requires them to wait at least 180 days from the date of first delinquency before reporting that debt.

States Vary Widely on Patient Protections from Medical Debt Lawsuits

Federal law considers initiating legal action to collect on unpaid medical bills to be an extraordinary collections action and also limits how much of a debtor’s paycheck can be garnished to pay a debt.

In most states, hospitals and debt buyers can sue patients to collect on unpaid medical bills. Three states limit when hospitals and/or collections agencies can initiate legal action. Illinois prohibits lawsuits against uninsured patients who demonstrate an inability to pay. Minnesota prohibits hospitals from giving “blanket approval” to collections agencies to pursue legal action, and Idaho prohibits the initiation of lawsuits until 90 days after the insurer adjudicates the claim, all appeals are exhausted, and the patient receives notice of the outstanding balance.

Liens and foreclosures.

Most states (32) do not limit hospitals, collections agencies, or debt buyers from placing a lien or foreclosing on a patient’s home to recover on unpaid medical bills. However, almost all states provide a homestead exemption, which protects some equity in a debtor’s home from being seized by creditors during bankruptcy. The amount of homestead exemption available to debtors varies from state to state, ranging from just $5,000 to the entire value of the home. Seven states have unlimited homestead exemptions, allowing debtors to fully shield their primary homes from creditors during bankruptcy. Additionally, Louisiana offers an unlimited homestead exemption for certain uninsured, low-income patients with at least $10,000 in medical bills.

Ten states prohibit or set limits on liens or foreclosures for medical debt. For example, New York and Maryland fully prohibit both liens and foreclosures because of medical debt, while California and New Mexico only prohibit them for certain low-income populations.

Wage garnishment.

Under federal law, the amount of wages garnished weekly may not exceed the lesser of: 25 percent of the employee’s disposable earnings, or the amount by which an employee’s disposable earnings are greater than 30 times the federal minimum wage. Twenty-one states exceed the federal ceiling for wage garnishment. Only a few states go further to prohibit wage garnishment for all or some patients. For example, New York fully prohibits wage garnishment to recover on medical debt for all patients, yet California only extends this protection for certain low-income populations. While New Hampshire does not prohibit wage garnishment, it requires the creditor to keep going back to court every pay period to garnish wages, which significantly limits creditors’ ability to garnish wages in practice.

Many States Have Hospital Reporting Requirements, But Few Are Robust

Federal law requires all nonprofit hospitals to submit an annual tax form including total dollar amounts spent on financial assistance and written off as bad debt. However, these reporting requirements do not extend to for-profit hospitals and lack granularity. States, as the primary regulators of hospitals, would likely benefit from more robust data collection processes to better understand the impact of medical debt and guide their oversight and enforcement efforts.

Currently, 32 states collect some of the following:

- financial data, including the total dollar amounts spent on financial assistance and/or bad debt

- financial assistance program data, including the numbers of applications received, approved, denied, and appealed

- demographic data on the populations most affected by medical debt

- information on the number of lawsuits and types of judgments sought by hospitals against patients.

Fifteen states explicitly require hospitals to report total dollar amounts spent on financial assistance and/or bad debt, while 11 states also require hospitals to report certain data related to their financial assistance programs. Most of these 11 states limit the data they collect to the numbers of applications received, approved, denied, and appealed. However, a handful of them go further and ask hospitals to report on the amount of financial assistance provided per patient, number of financial assistance applicants approved and denied by zip code, number of payment plans created and completed, and number of accounts sent to collections.

Five states require hospitals to further break down their financial assistance data by race, ethnicity, gender, and/or preferred or primary language. For example, Maryland requires hospitals to break down the following data by race, ethnicity, and gender: the bills hospitals write off as bad debt and the number of patients against whom the hospital or the debt collector has filed a lawsuit.

Only Oregon asks hospitals to report on the number of patient accounts they refer for collections and extraordinary collections actions.

Discussion and Policy Implications

In 2022, the federal government announced administrative measures targeting the medical debt problem, which included launching a study of hospital billing practices and prohibiting federal government lenders from considering medical debt when making decisions on loan and mortgage applications. Although these measures will help some, only federal legislation and enhanced oversight will likely address current gaps in federal standards.

States can also fill the gaps in federal patient protections by improving access to financial assistance, ensuring that nonprofit hospitals are earning their tax exemption, and protecting patients against aggressive billing and collections practices. States also can leverage underutilized usury laws to protect their residents from medical debt.

Finding the most effective ways to enforce these standards at the state level could also protect patients. Absent oversight and enforcement, patients from underserved communities continue to face harm from medical debt, even when states require hospitals to provide financial assistance and prohibit them from engaging in aggressive collections practices. Bolstering reporting requirements alone would not likely ensure compliance, but states could protect patients by strengthening their penalties, providing patients with the right to sue noncompliant hospitals, and devoting funding to increase oversight by state agency officials.

To develop a comprehensive medical debt protection framework, states could also bring together state agencies like their departments of health, insurance, and taxation, as well as their state attorney general’s office. Creating an interagency office dedicated to medical debt protection would allow for greater efficiency and help the state build expertise to take on the well-resourced debt collection and hospital industries.

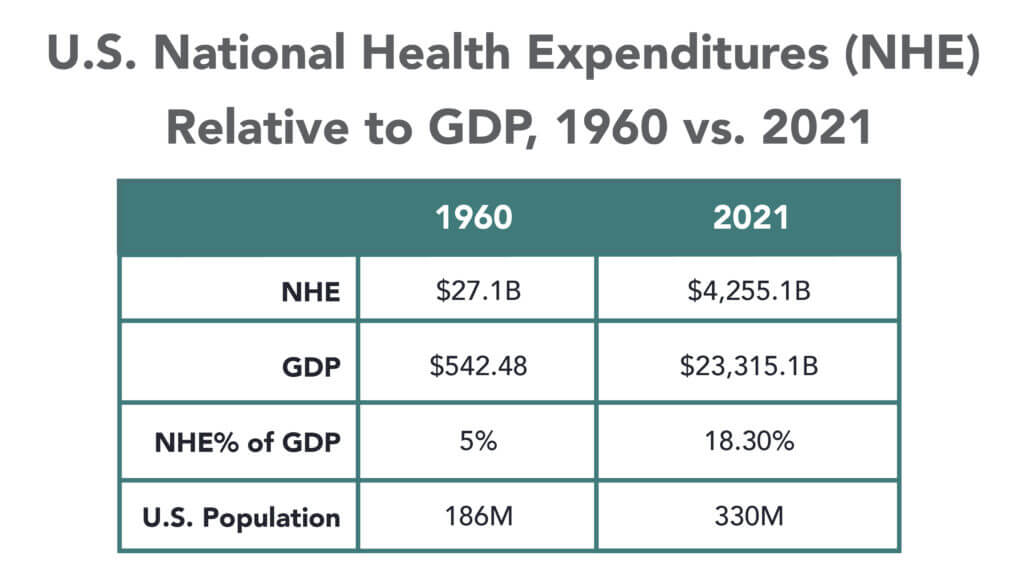

Still, these measures only address the symptoms of the bigger problem: the unaffordability of health care in the United States. Federal and state policymakers who want to have a meaningful impact on the medical debt problem could consider the protections discussed in this report as part of a broader plan to reduce health care costs and improve coverage.