https://www.healthcaredive.com/news/despite-turbulence-in-h1-no-avalanche-of-health-systems-downgrades/584353/?utm_source=Sailthru&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Issue:%202020-09-02%20Healthcare%20Dive%20%5Bissue:29437%5D&utm_term=Healthcare%20Dive

“It’s new territory, which is why we’re taking that measured approach on rating actions,” Suzie Desai, senior director at S&P, said.

The healthcare sector has been bruised from the novel coronavirus and the effects are likely to linger for years, but the first half of 2020 has not resulted in an avalanche of hospital and health system downgrades.

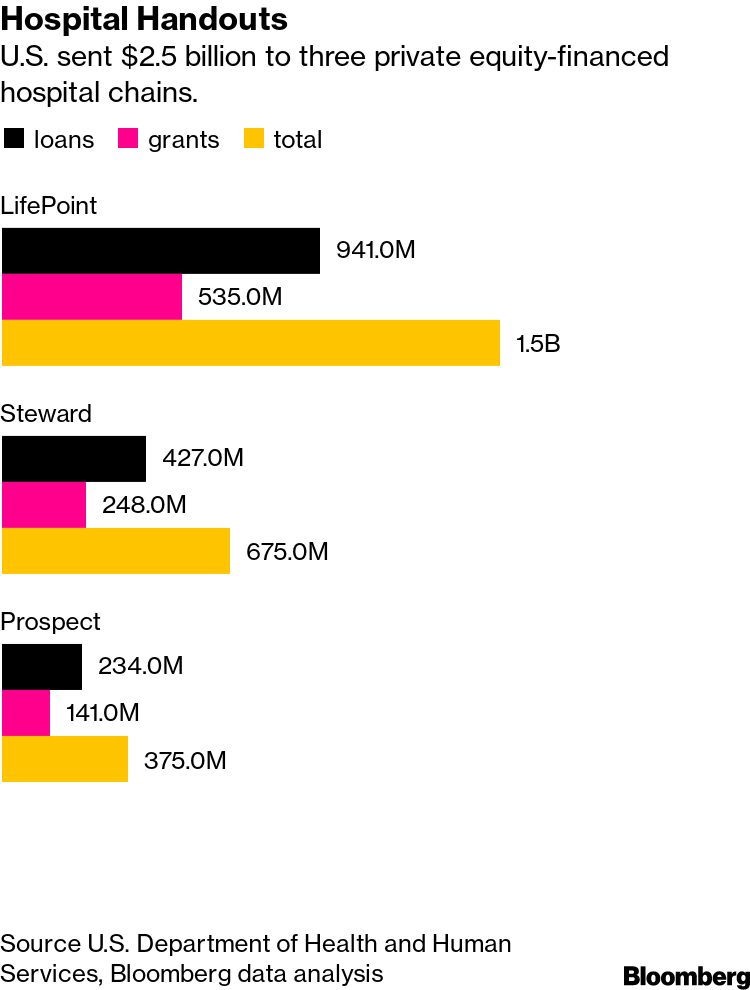

At the outset of the pandemic, some hospitals warned of dire financial pressures as they burned through cash while revenue plunged. In response, the federal government unleashed $175 billion in bailout funds to help prop up the sector as providers battled the effects of the virus.

Still, across all of public finance — which includes hospitals — the second quarter saw downgrades outpacing upgrades for the first time since the second quarter of 2017.

S&P characterized the second quarter as a “historic low” for upgrades across its entire portfolio of public finance credits.

“While only partially driven by the coronavirus, the second quarter was the first since Q2 2017 with the number of downgrades surpassing upgrades and by the largest margin since Q3 2014,” according to a recent Moody’s Investors Service report.

Through the first six months of this year, Moody’s has recorded 164 downgrades throughout public finance and, more specifically, 27 downgrades among the nonprofit healthcare entities it rates.

By comparison, Fitch Ratings has recorded 14 nonprofit hospital and health system downgrades through July and just two upgrades, both of which occurred before COVID-19 hit.

“Is this a massive amount of rating changes? By no means,” Kevin Holloran, senior director of U.S. Public Finance for Fitch, said of the first half of 2020 for healthcare.

Also through July, S&P Global recorded 22 downgrades among nonprofit acute care hospitals and health systems, significantly outpacing the six healthcare upgrades recorded over the same period.

“It’s new territory, which is why we’re taking that measured approach on rating actions,” Suzie Desai, senior director at S&P, said.

Still, other parts of the economy lead healthcare in terms of downgrades. State and local governments and the housing sector are outpacing the healthcare sector in terms of downgrades, according to S&P.

Virus has not ‘wiped out the healthcare sector’

Earlier this year when the pandemic hit the U.S., some made dire predictions about the novel coronavirus and its potential effect on the healthcare sector.

Reports from the ratings agencies warned of the potential for rising covenant violations and an outlook for the second quarter that would result in the “worst on record,“ one Fitch analyst said during a webinar in May.

That was likely “too broad of a brushstroke,” Holloran said. “It has not come in and wiped out the healthcare sector,” he said. He attributes that in part to the billions in financial aid that the federal government earmarked for providers.

Though, what it has revealed is the gaps between the strongest and weakest systems, and that the disparities are only likely to widen, S&P analysts said during a recent webinar.

The nonprofit hospitals and health systems pegged with a downgrade have tended to be smaller in size in terms of scale, lower-rated already and light on cash, Holloran said.

Still, some of the larger health systems were downgraded in the first half of the year by either one of the three rating agencies, including Sutter Health, Bon Secours Mercy Health, Geisinger, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and Care New England.

“This is something that individual management of a hospital couldn’t control,” said Rick Gundling, senior vice president of Healthcare Financial Management Association, which has members from small and large organizations. “It wasn’t a bad strategy — that goes into a downgrade. This happened to everybody.”

Deteriorating payer mix

Looking forward, some analysts say they’re more concerned about the long-term effects for hospitals and health systems that were brought on by the downturn in the economy and the virus.

One major concern is the potential shift in payer mix for providers.

As millions of people lose their job they risk losing their employer-sponsored health insurance. They may transition to another private insurer, Medicaid or go uninsured.

For providers, commercial coverage typically reimburses at higher rates than government-sponsored coverage such as Medicare and Medicaid. Treating a greater share of privately insured patients is highly prized.

If providers experience a decline in the share of their privately insured patients and see a growth in patients covered with government-sponsored plans, it’s likely to put a squeeze on margins.

The shift also poses a serious strain for states, and ultimately providers. States are facing a potential influx of Medicaid members at the same time state budgets are under tremendous financial pressure. It raises concerns about whether states will cut rates to their Medicaid programs, which ultimately affects providers.

Some states have already started to re-examine and slash rates, including Ohio.