https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/finance/42-hospitals-closed-filed-for-bankruptcy-this-year.html?utm_medium=email

From reimbursement landscape challenges to dwindling patient volumes, many factors lead hospitals to shut down or file for bankruptcy. At least 42 hospitals across the U.S. have closed or entered bankruptcy this year, and the financial challenges caused by the COVID-19 pandemic may force more hospitals to do the same in coming months.

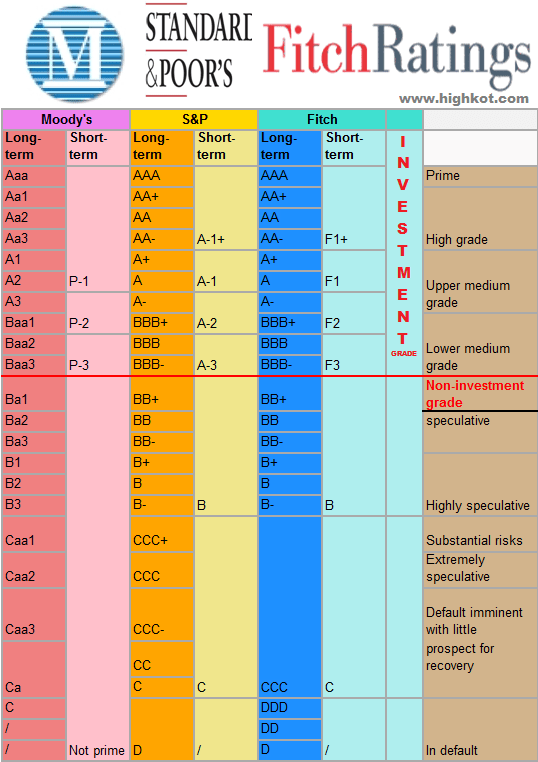

COVID-19 has created a cash crunch for many hospitals across the nation. They’re estimated to lose $200 billion between March 1 and June 30, according to a report from the American Hospital Association. More than $161 billion of the expected revenue losses will come from canceled services, including nonelective surgeries and outpatient treatment. Moody’s Investors Service said the sharp declines in revenue and cash flow caused by the suspension of elective procedures could cause more hospitals to default on their credit agreements this year than in 2019.

Below are the provider organizations that have filed for bankruptcy or closed since Jan. 1, beginning with the most recent. They own and operate a combined 42 hospitals.

Our Lady of Bellefonte Hospital (Ashland, Ky.)

Bon Secours Mercy Health closed Our Lady of Bellefonte Hospital in Ashland, Ky., on April 30. The 214-bed hospital was originally slated to shut down in September of this year, but the timeline was moved up after employees began accepting new jobs or tendering resignations. Bon Secours cited local competition as one reason for the hospital closure. Despite efforts to help sustain hospital operations, Bon Secours was unable to “effectively operate in an environment that has multiple acute care facilities competing for the same patients, providers and services,” the health system said.

Williamson (W.Va.) Hospital

Williamson Hospital filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in October and was operating on thin margins for months before shutting down on April 21. The 76-bed hospital said a drop in patient volume due to the COVID-19 pandemic forced it to close. CEO Gene Preston said the decline in patient volume was “too sudden and severe” for the hospital to sustain operations.

Decatur County General Hospital (Parsons, Tenn.)

Decatur County General Hospital closed April 15, a few weeks after the local hospital board voted to shut it down. Decatur County Mayor Mike Creasy said the closure was attributable to a few factors, including rising costs, Tennessee’s lack of Medicaid expansion and broader financial challenges facing the rural healthcare system in the U.S.

Quorum Health (Brentwood, Tenn.)

Quorum Health and its 23 hospitals filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy April 7. The company, a spinoff of Franklin, Tenn.-based Community Health Systems, said the bankruptcy filing is part of a plan to recapitalize the business and reduce its debt load.

UPMC Susquehanna Sunbury (Pa.)

UPMC Susquehanna Sunbury closed March 31. Pittsburgh-based UPMC announced plans in December to close the rural hospital, citing dwindling patient volumes. Sunbury’s population was 9,905 at the 2010 census, down more than 6 percent from 10 years earlier. Though the hospital officially closed its doors in March, it shut down its emergency department and ended inpatient services Jan. 31.

Fairmont (W.Va.) Regional Medical Center

Irvine, Calif.-based Alecto Healthcare Services closed Fairmont Regional Medical Center on March 19. Alecto announced plans in February to close the 207-bed hospital, citing financial challenges. “Our plans to reorganize some administrative functions and develop other revenue sources were insufficient to stop the financial losses at FRMC,” Fairmont Regional CEO Bob Adcock said. “Our efforts to find a buyer or new source of financing were unsuccessful.” Morgantown-based West Virginia University Medicine will open a 10-bed hospital with an emergency department at the former Fairmont Regional Medical Center by the end of June.

Sumner Community Hospital (Wellington, Kan.)

Sumner Community Hospital closed March 12 without providing notice to employees or the local community. Kansas City, Mo.-based Rural Hospital Group, which acquired the hospital in 2018, cited financial difficulties and lack of support from local physicians as reasons for the closure. “Lack of support from the local medical community was the primary reason we are having to close the hospital,” RHG said. “We regret having to make this decision; however, despite operating the hospital in the most fiscally responsible manner possible, we simply could not overcome the divide that has existed from the time we purchased the hospital until today.”

Randolph Health

Randolph Health, a single-hospital system based in Asheboro, N.C., filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy March 6. Randolph Health leaders have taken several steps in recent years to improve the health system’s financial picture, and they’ve made progress toward that goal. Entering Chapter 11 bankruptcy will allow Randolph Health to restructure its debt, which officials said is necessary to ensure the health system continues to provide care for many more years.

Pickens County Medical Center (Carrollton, Ala.)

Pickens County Medical Center closed March 6. Hospital leaders said the closure was attributable to the hospital’s unsustainable financial position. A news release announcing the closure specifically cited reduced federal funding, lower reimbursement from commercial payers and declining patient visits.

The Medical Center at Elizabeth Place (Dayton, Ohio)

The Medical Center at Elizabeth Place, a 12-bed hospital owned by physicians in Dayton, Ohio, closed March 5. The closure came after years of financial problems. In January 2019, the Medical Center at Elizabeth Place lost its certification as a hospital, meaning it couldn’t bill Medicare or Medicaid for services. Sixty to 65 percent of the hospital’s patients were covered through the federal programs.

Mayo Clinic Health System-Springfield (Minn.)

Mayo Clinic Health System closed its hospital in Springfield, Minn., on March 1. Mayo announced plans in December to close the hospital and its clinics in Springfield and Lamberton, Minn. At that time, James Hebl, MD, regional vice president of Mayo Clinic Health System, said the facilities faced staffing challenges, dwindling patient volumes and other issues. The hospital in Springfield is one of eight hospitals within a less than 40-mile radius, which has led to declining admissions and low use of the emergency department, Dr. Hebl said.

Faith Community Health System

Faith Community Health System, a single-hospital system based in Jacksboro, Texas and part of the Jack County (Texas) Hospital District, first entered Chapter 9 bankruptcy — a bankruptcy proceeding that offers distressed municipalities protection from creditors while a repayment plan is negotiated — in February. The bankruptcy court dismissed the case May 26 at the request of the health system. The health system asked the court to dismiss the bankruptcy case to allow it to apply for a Paycheck Protection Program loan through a Small Business Association lender. On June 11, Faith Community Health System reentered Chapter 9 bankruptcy.

Pinnacle Healthcare System

Overland Park, Kan.-based Pinnacle Healthcare System and its hospitals in Missouri and Kansas filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy on Feb. 12. Pinnacle Regional Hospital in Boonville, Mo., formerly known as Cooper County Memorial Hospital, entered bankruptcy about a month after it abruptly shut down. Pinnacle Regional Hospital in Overland Park, formerly called Blue Valley Hospital, closed about two months after entering bankruptcy.

Central Hospital of Bowie (Texas)

Central Hospital of Bowie abruptly closed Feb. 4. Hospital officials said the facility was shut down to enable them to restructure the business. Hospital leaders voluntarily surrendered the license for Central Hospital of Bowie.

Ellwood City (Pa.) Medical Center

Ellwood City Medical Center officially closed Jan. 31. The hospital was operating under a provisional license in November when the Pennsylvania Department of Health ordered it to suspend inpatient and emergency services due to serious violations, including failure to pay employees and the inability to offer surgical services. The hospital’s owner, Americore Health, suspended all clinical services at Ellwood City Medical Center Dec. 10. At that time, hospital officials said they hoped to reopen the facility in January. Plans to reopen were halted Jan. 3 after the health department conducted an onsite inspection and determined the hospital “had not shown its suitability to resume providing any health care services.”

Thomas Health (South Charleston, W.Va.)

Thomas Health and its two hospitals filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy on Jan. 10. In an affidavit filed in the bankruptcy case, Thomas Health President and CEO Daniel J. Lauffer cited several reasons the health system is facing financial challenges, including reduced reimbursement rates and patient outmigration. The health system announced June 18 that it reached an agreement in principle with a new capital partner that would allow it to emerge from bankruptcy.

St. Vincent Medical Center (Los Angeles)

St. Vincent Medical Center closed in January, roughly three weeks after El Segundo, Calif.-based Verity Health announced plans to shut down the 366-bed hospital. Verity, a nonprofit health system that entered Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2018, shut down St. Vincent after a deal to sell four of its hospitals fell through. In April, Patrick Soon-Shiong, MD, the billionaire owner of the Los Angeles Times, purchased St. Vincent out of bankruptcy for $135 million.

Astria Regional Medical Center (Yakima, Wash.)

Astria Regional Medical Center filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in May 2019 and closed in January. When the hospital closed, 463 employees lost their jobs. Attorneys representing Astria Health said the closure of Astria Regional Medical Center, which has lost $40 million since 2017, puts Astria Health in a better financial position. “As a result of the closure … the rest of the system’s cash flows will be sufficient to safely operate patient care operations and facilities and maintain administrative solvency of the estate,” states a status report filed Jan. 20 with the bankruptcy court.