https://www.commercehealthcare.com/trends-insights/2023/healthcare-finance-trends-for-2023

This annual look at high-impact trends affecting healthcare in the coming year is based on evaluation of current industry research data. Healthcare Finance Trends for 2023 (Trends) explores eight themes identified by CommerceHealthcare® ranging across four areas:

- Financial. Providers enter the year contending with multiple financial stress points. They will also seek growth in technology-enabled remote care.

- Patient financial experience. The need to drive not only improvement but also personalization of the financial experience is paramount. A central role will be played by patient financing programs which will see growing demand in 2023.

- Trust. Building trust with all constituencies is explored as a linchpin for long-term provider success. The latest findings on cybersecurity show that this contributor to trust will continue to consume leadership attention.

- Digital transformation. Pursuit of digital-first operations is accelerating, with the finance area an important focus. Emerging payment modes are finding a home in healthcare’s digital finance landscape.

This report’s consistent message is that these trends intersect in ways that compound both the challenges and the upside potential of strategies that address them.

1. Multiple Financial Stress Points Will Constrain Options

Healthcare’s financial predicament for the next 12–18 months is being described in strong terms. Citing $450 billion of EBITDA that could be in jeopardy, more than half of the industry’s project profit pool by 2027, one analyst suggests “a gathering storm.” Another perceives “broad and serious threats” as “elevated expenses” erode margins and exact “a profound financial toll.” Fitch Ratings issued a “deteriorating” outlook for nonprofit health systems.

These financial headwinds are upending healthcare’s traditional status as “recession-proof.” It is helpful to probe the multiple forces in play, the urgent workforce management challenge, and the varied solution set.

Multiple stress factors at work

Observing that margins will be down 37% in 2022 relative to pre-pandemic, a recent stark assessment concluded, “U.S. hospitals are likely to face billions of dollars in losses — which would result in the most difficult year for hospitals and health systems since the beginning of the pandemic.”

A confluence of factors is exacerbating the stress for 2023:

- Rising acuity levels. Over two-thirds of surveyed C-suite executives said patient health has worsened from pandemic-induced delayed care. The upshot, stated by 27% of CFOs, is rising expenses due to higher acuity. Inpatient days are projected to increase at an 8% rate over the coming decade.

- Reimbursement gaps and inflation. Commercial and government reimbursement rates are not keeping pace with rising costs. Surging inflation is widening this gap. Hospitals are also reporting substantial insurer payment delays and denials.

- Investment declines. Stock and bond market declines have removed a cushion for operating weakness. Market uncertainty will complicate 2023 portfolio management.

Persistent workforce concerns remain center stage

Burnout and shortages have disrupted the clinical workforce. Nearly 60% of physician, advanced practice provider and nurse survey respondents said their teams are not adequately staffed, and 40% lack resources to operate at full potential. Many providers face extreme to moderate shortages of allied health professionals.

The problem extends beyond the clinical. A survey saw 48% of respondents experiencing severe labor deficiencies in revenue cycle management (RCM) and billing, and one in four finance leaders must fill over 20 positions to be fully staffed.

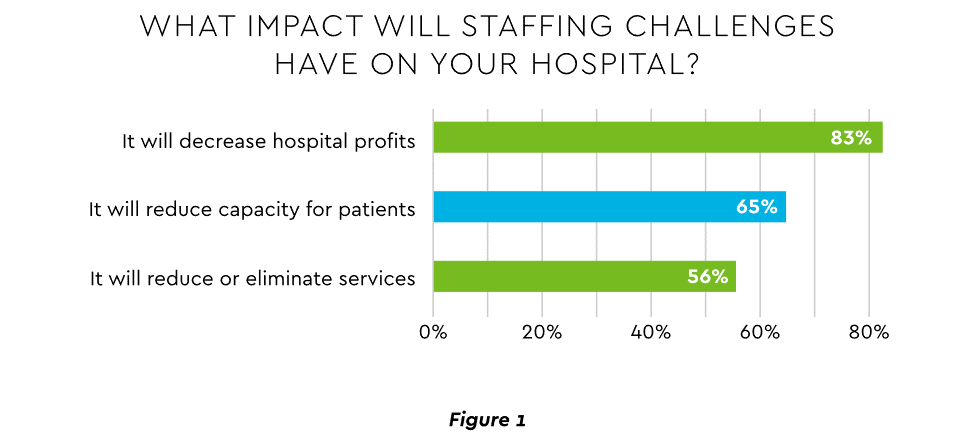

An executive outlook highlighted demonstrable impact on financial performance and growth from these workforce problems, citing reductions in profitability, capacity and service (Figure 1).1

View PDF of Figure 1 chart[PDF]

Several studies detail negative outcomes:

- Expenses. Hospital employee expense is expected to increase $57 billion from 2021 to 2022, with contract labor ballooning another $29 billion. Average weekly earnings are up 21.1% since early 2022. Half of medical practices budgeted higher staff cost-of-living increases in 2022. Shortages plague post-acute facilities as well. Their reduced capability to accept discharged patients is lengthening many hospitals’ patient stays.

- Capacity constraint. Two-thirds of healthcare leaders identify “ability to meet demand” as their top workforce concern, suggesting a “looming capacity gap between future demand and labor supply.”

Range of measures being deployed

Health systems, hospitals and practices will vigorously pursue at least four direct actions to overcome the financial and staffing hurdles:

- Cost cutting. Expense control will be paramount and “hospitals will be forced to take aggressive cost-cutting measures.” McKinsey estimates total industry administrative savings of $1 trillion through multiple aggressive changes.

- Service line rationalization. Providers are rethinking how they deliver services to optimize efficiency. One path is utilizing “lower level” healthcare professionals in ways that free RNs and LPAs for more complex work suited to their top skills. Integrating remote care into the mix is another core element of the strategy.

- Recruitment and retention programs. Attracting and retaining talent is crucial. Compensation is one avenue. Over two-thirds of organizations are offering signing bonuses for allied health professionals. Some are instituting value-based payments for physicians, offering salary floors to protect from drops in patient volume. CFOs and CNOs are joining forces to invest in nurse retention strategies.

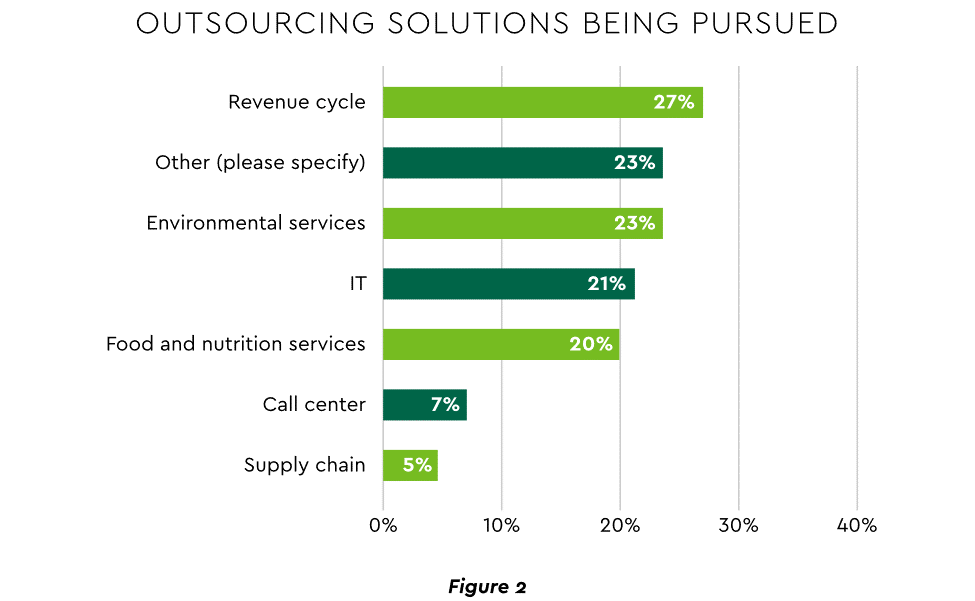

- Staffing management. An increasingly popular tool to reduce labor cost and optimize staff resources is outsourcing. Figure 2 shows that RCM is leading the way among those using the solution.

View PDF of Figure 2 chart[PDF]

2. Growth Strategies Favor Outpatient, Virtual, Acute Home Care

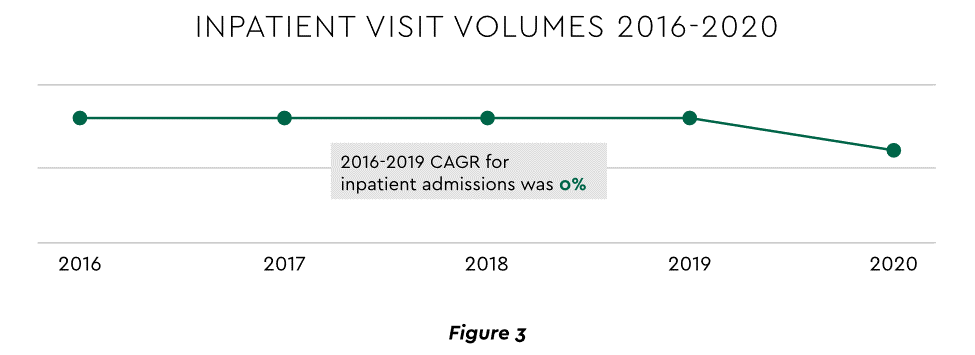

Pursuing top line growth in tandem with reining in expenses is essential. Inpatient volume growth has been tepid for several years ─ essentially flat in the 2016–20 period (Figure 3).

View PDF of Figure 3 chart[PDF]

Leaders have been pivoting to outpatient and virtual care to diversify revenue streams. Two high-potential 2023 growth tracks in this sector merit deeper assessment.

Telehealth

Considerable evidence attests to strong commitment to telehealth and remote care. Sixty-three percent of physicians worldwide expect most consultations to be performed remotely within 10 years. Approximately 40% of health centers are using remote patient monitoring today. Consumers are also positive: 94% definitely or probably will use telehealth again, 57% prefer it for regular mental health visits and 61% use it for convenient care.

Telehealth is still in early stages of maturity. Only 4% of surveyed top executives consider their organization proficient at implementing remote care. Healthcare is also recognizing that a full telehealth ecosystem must be constructed. A physician leader explained that the industry’s early telehealth incarnations failed to build “virtual-only environments or really drive e-consults as a way of doing things.” A vital ecosystem demands alterations to current contracts, coding, collections, patient financing, staff training and other business practices.

Hospital-at-Home (HaH)

Health systems see particularly promising growth in the provision of acute care in patients’ home settings, including post-surgical and cancer treatment. The federal government has already allowed waivers to 114 systems and 256 hospitals to obtain inpatient-level reimbursement for acute care at home. However, these waivers were prompted by the pandemic and are slated to end in early 2023. The renewal uncertainty has stymied some activity and represents an overhang on the opportunity. However, enthusiasm appears strong, and 33% of hospitals in a recent poll said they would be prone to continue HaH even without renewal.

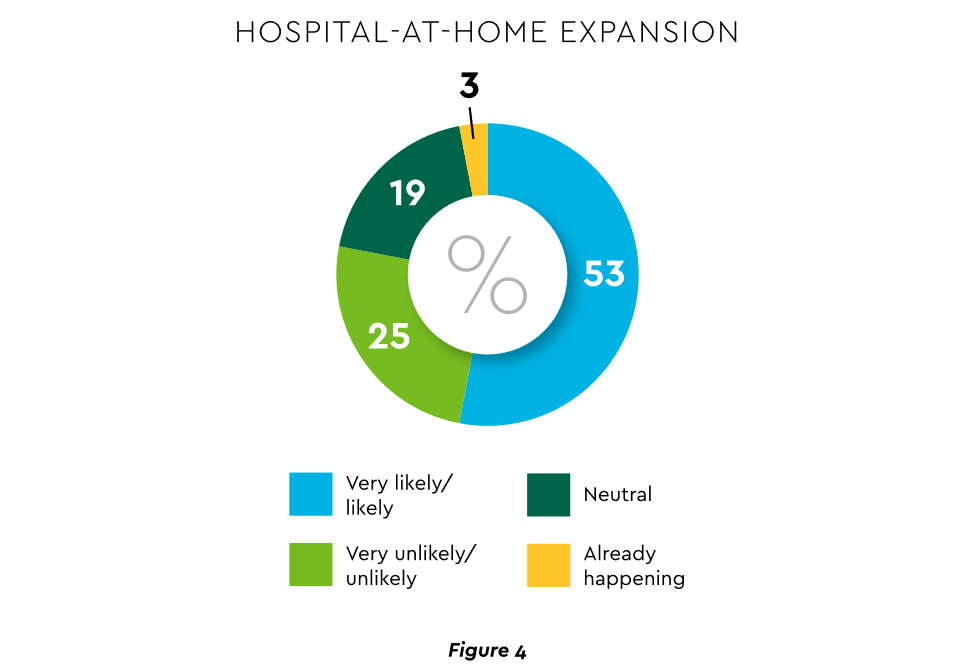

The forecasts are encouraging. Over half of hospitals believe it likely they will utilize HaH for at least half of their chronically ill patients over the next several years (Figure 4).

View PDF of Figure 4 chart[PDF]

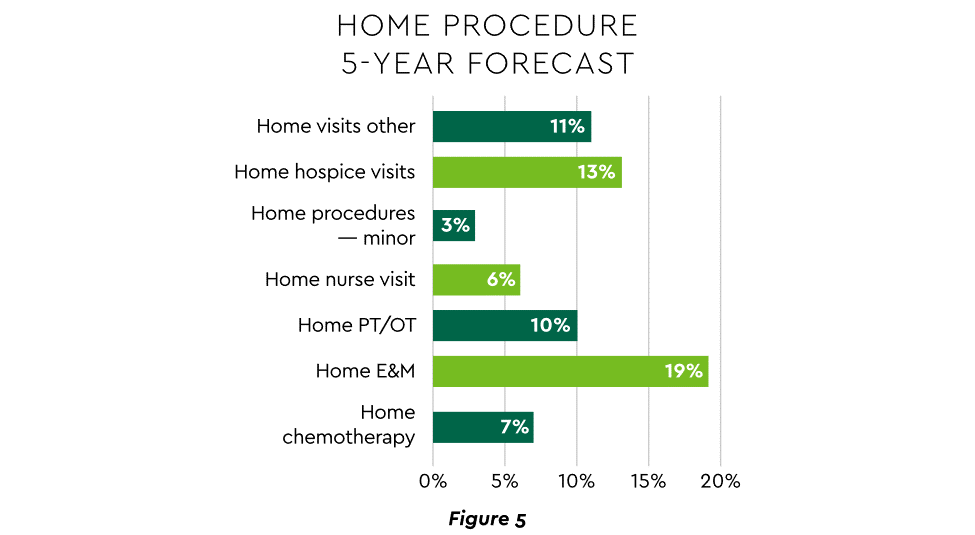

HaH exists within a broader matrix of home care, and solid growth is anticipated across the range of home procedures (Figure 5).

View PDF of Figure 5 chart[PDF]

Harvesting the HaH potential will require implementation of current and emerging enabling technologies in remote monitoring, high-speed networks and artificial intelligence that generates algorithmic guidance for caregivers and patients alike.

3. Strong Drive to Improve and Personalize the Patient Financial Experience

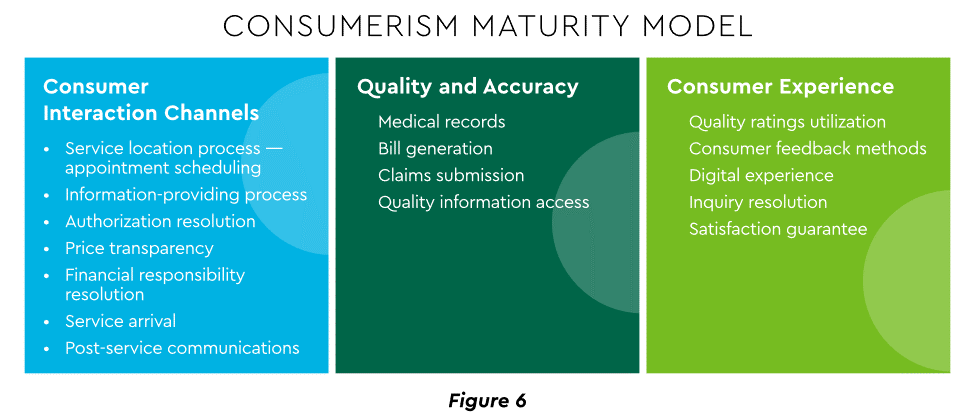

Today’s healthcare market dynamics place a premium on positive patient experiences. The goal is to deliver “an empathetic relationship between customers and brands built on what the customer wants and how they want to be treated.” It is a complex undertaking, with numerous touchpoints as captured in HFMA’s Consumerism Maturity Model (Figure 6).

View PDF of Figure 6 chart[PDF]

An array of studies underscores the value proposition for intense provider focus on patient financial experience:

- Sixty-one percent of consumers said that ease of making payments is very or somewhat important in decisions to continue seeing a doctor. Over half of patients also said text message reminders make them very or somewhat more likely to pay a bill faster than usual.

- Thirty-five percent of respondents “have changed or would change healthcare providers to get a better digital patient administrative experience.”

- A quality financial experience encompasses “simplified explanations, consolidated bills that match one’s health plan benefits, clear language displaying patient liability and payment options.”35

Significantly improving the financial experience requires a unified strategy, not just a collection of individual initiatives. Three threads to such a strategy will be prominent in 2023.

Using a Digital Front Door

Organizations have been moving swiftly to channel many patient financial transactions through an integrated Digital Front Door (DFD). This approach offers patients a singular online point of access and intelligent navigation to needed services.

Growth is accelerating. A DFD is their patients’ first contact point for 55% of responding organizations, according to one technology survey. A leading forecaster sees 65% of patients engaging services via digital front doors by 2023.

Expanding price transparency

Mandates for full price transparency and “no surprises” billing are in effect, but estimates of compliance are mixed. An analysis of 2,000 hospitals determined that only 16% met the requirement to post an online “machine readable” file displaying clear charges for 300 “shoppable services.” Another assessment showed a more substantial 76% of hospitals had posted files, and 55% were deemed “complete.” One provision of interest to practices is the “good faith estimate” of expected charges required to be given to uninsured and self-pay individuals when they schedule visits.

CommerceHealthcare® has worked with clients to enhance the patient financial experience by complementing their website pricing data with clear information on patient financing options and enrollment access. Bill pay information can also be added for one-stop guidance.

Personalizing the experience

Beyond choice and convenience, the deeper objective is truly personalized experiences throughout the care journey. The words of leading analysts best define the drive to personalize:

- “Tomorrow’s healthcare experience will be built by patients tailoring their own experience.”

- “By 2024, 30% of chronic care patients will truly own and openly leverage their personal health information to advocate for, secure, and realize better personalized care.”

Opportunities abound to personalize the patient financial experience. Automating manual processes establishes a foundation. Patient financing with no- or low-interest credit lines and flexible terms can produce monthly payment schedules tailored to each patient’s needs. Refunds can be made through multiple payment modes to meet varying patient preferences.

4. Evidence Underscores Growing Demand for Patient Financing

Emphasizing patient financing as part of the overall experience is powerful. Patients continue to struggle paying for care. Recent granular data details three related forces at work.

Meeting care costs difficult for many patients

Commonwealth Fund found that 42% of individuals had problems paying medical bills or were paying off medical debt during the past year, while 49% were unable to pay an unexpected

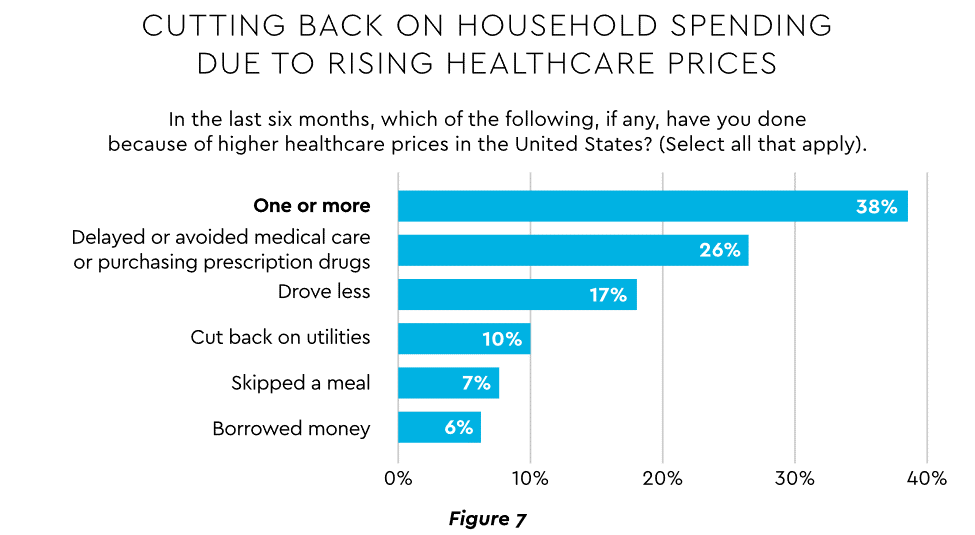

$1,000 medical bill.42 Health costs trigger reduction in a range of personal expenditures, led by deferring or avoiding care and drugs (Figure 7).

View PDF of Figure 7 chart[PDF]

Twenty-eight percent of Americans now describe themselves as less prepared than last year to pay for routine or unanticipated care.

Patient obligation for care costs still rising

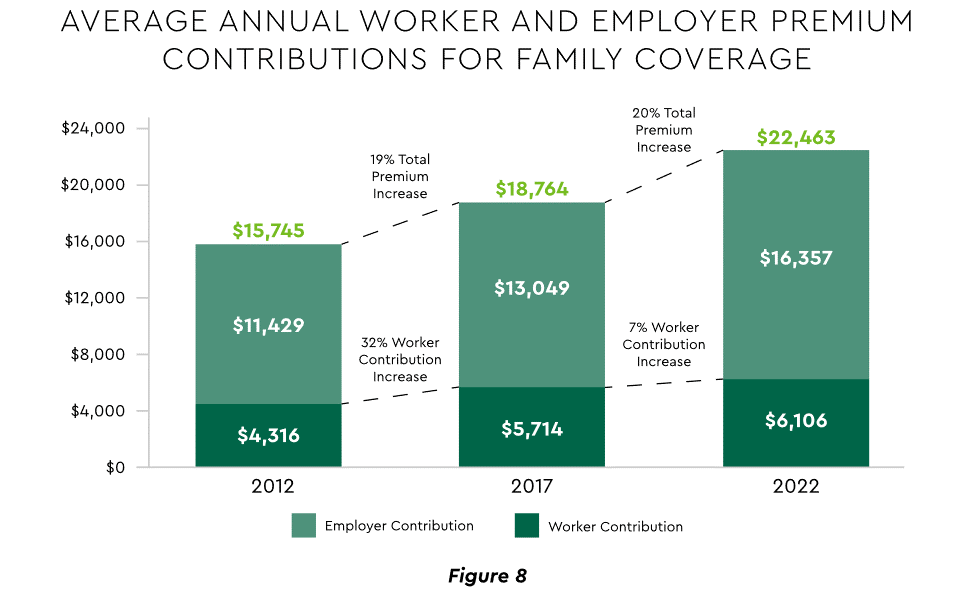

Patient obligation continues its upward march. Insurance premiums have climbed steadily for both the insured and their employers, and employees now pay over $6,000 annually on average for family coverage (Figure 8).45

View PDF of Figure 8 chart[PDF]

High deductible health plans (HDHP) also place substantial burden on the patient. Through 2021, 28% of workers were enrolled in an HDHP with an average family deductible of $4,705. Employer satisfaction with these plans is high, auguring further expansion.

Providers feeling the financial effects

Patient payment difficulties are clearly impacting provider financials. A recent in-depth analysis uncovered substantial self-pay issues:

- Self-pay accounts represented 60% of 2021 patient bad debt, up from 11% in 2018.

- Nearly 18% of patient balances were over $7,500 and 17% over $14,000. Collections were noticeably lower at these balances.

Multiple chronic conditions add to the problem. A recent extensive analysis concluded: “Among individuals with medical debt in collections, the estimated amount increased with the number of chronic conditions ($784 for individuals with no conditions to $1,252 for individuals with 7–13).”

For their part, providers will be encouraged to broaden patient financing programs. Patients are certainly interested. When asked, 62% of consumers indicated they would use financing options or creative payment plans if available for large bill amounts. Many health systems, hospitals and practices will turn to outside help to satisfy the demand. A recent analysis recommended that health systems “consider keeping shorter-term payment plans in-house and extended term plans through external partnerships.”

Organizations will also need to step up their communications. A survey revealed that 64% of patients were unaware that their doctors and hospitals offered payment plans or financial help.

5. Building Trust Becoming a Critical Success Factor

Trust has emerged as a paramount issue today for most organizations as they encounter an “imperative to build trust and transparency among different stakeholder groups — employees, customers, suppliers, regulators and the communities in which they operate.” Healthcare is no exception, and the trust issue is growing in both complexity and urgency.

Healthcare’s trust gap

Trust in healthcare took a hit from the COVID-19 experience. A spring 2022 HFMA survey recorded 44% of finance leaders saying they perceived decreased patient trust. Between April 2020 and December 2021, the percentage of Americans who trusted information from doctors “a great deal” declined by 23%, from hospitals 21%, and from nurses 16%. The patient financial experience also faces “drivers of mistrust,” according to surveyed leaders who cited general payment confusion (58%), surprise billing (39%), high prices of commodity items (28%) and lack of price transparency (26%). Building trust reaps dividends. People who trust their providers are five times more likely to stay with them than those who are neutral or distrustful.

Strategies for building trust

Industry experts promote several approaches to galvanize trust among all constituencies:

- Commitment. Embedding trust deeply in the organization requires full support from senior leadership.

- Data transparency and governance. IDC predicts that “by end of 2023, 20% of expenses on care integration solutions will be centered around ‘trust’ to protect data, workflows and transactions.”

- Reliance on fewer business partners. Many health systems, hospitals and practices are reducing their number of vendors in order to focus on a set of trusted long-term partners. For example, almost two-thirds of surveyed providers said they were seeking to streamline the number of software solutions over the next year.

The bank partner advantage

A provider’s banking relationship can yield valuable collaboration in the trust-building endeavor. Banks enjoy solid trust among consumers. As an example, 53.4% of consumers rated banks as most trusted to provide payment “super apps” and financial digital front doors ─ exceeding the next closest source by 10 points.

6. Cybersecurity in 2023: No Rest for the Weary

Cybersecurity is part of the trust calculus and has become an evergreen topic in healthcare. Compromised data and ransomware attacks are ongoing and leaders must continually refine their understanding in at least three areas: the overall security landscape, particular financially related considerations and contemporary security defenses.

The current landscape

The latest statistics quantify the cyber assault on healthcare:

- Incidence. 89% of organizations suffered at least one attack in the past 12 months with the average number at 43.

- Cost. A provider’s most serious attack costs an average of $4.4 million. IBM calculated healthcare’s average total cost of a breach at $10.1 million, up 42% since 2020.

- Attack Characteristics. Healthcare data types most commonly compromised are personal (58%), medical (46%), and credentials (29%). Organizations have an exposure to an average of over 26,000 network-connected devices. A disturbing finding is that those healthcare institutions that paid ransom got back only 65% of their data in 2021.

Specific financial considerations

Finance leaders will also need awareness of the following:

- Cyberattacks could affect credit ratings and are often a component of Environmental, Social and Governance assessments.

- Financial outsourcing requires monitoring. A recent news story chronicled an accounts receivable firm’s breach that exposed individual information, account balances and payments.

- Cyber insurance premiums are likely to increase substantially.

Responses/tools

Beyond a host of management and monitoring tools being deployed, a strategic philosophy is rapidly gaining ground. The “zero trust” model sounds counter to the trust-building mindset described earlier, but it has become essential. It “denies access to applications and data by default,” and 58% of hospitals and health systems have a zero trust initiative in place. Another 37% intend to implement one within 12–18 months.

Cybersecurity investment will challenge CFOs in 2023, especially in areas such as talent. Cybersecurity worker availability is estimated to satisfy only 68% of open positions. Banking partners will also be expected to play an important role. Over the years, major banks have become “leaders in enhancing cyber strategy and investing in cyber defenses, processes and talent.”

7. Digital Transformation of Finance In Focus

Digital transformation is fundamental to healthcare’s business and care delivery model changes. IBM’s website succinctly captures the goal, “Digital transformation means adopting digital-first customer, business partner, and employee experiences.” A leading forecaster believes 70% of healthcare organizations will rely on digital-first strategies by 2027.

Transformation efforts need to accelerate. One study showed that “digital, technology and analytics strategies exist for nearly all organizations, yet only 30% have begun to execute on those plans.”

One functional segment ramping up digital transformation is finance. According to a recent survey, 94% of CFOs and senior leaders stated that such efforts will be at the forefront of financial operations and strategy for 2023–2024, and 79% described it as an “absolute need” for “commercial stabilization and long-term survival of their healthcare organization.”

Advanced technology is gaining traction. Many see optimization in combining robotic process automation (RPA), artificial intelligence and machine learning to create “intelligent automation.” Together, these technologies create algorithms to automate decisions that guide “robotic” software to perform financial actions and thereby reduce manual labor.

Getting to digital-first in finance and across the enterprise has several critical success factors. These include sustained commitment, a platform-centric mindset and effective governance.

Commitment

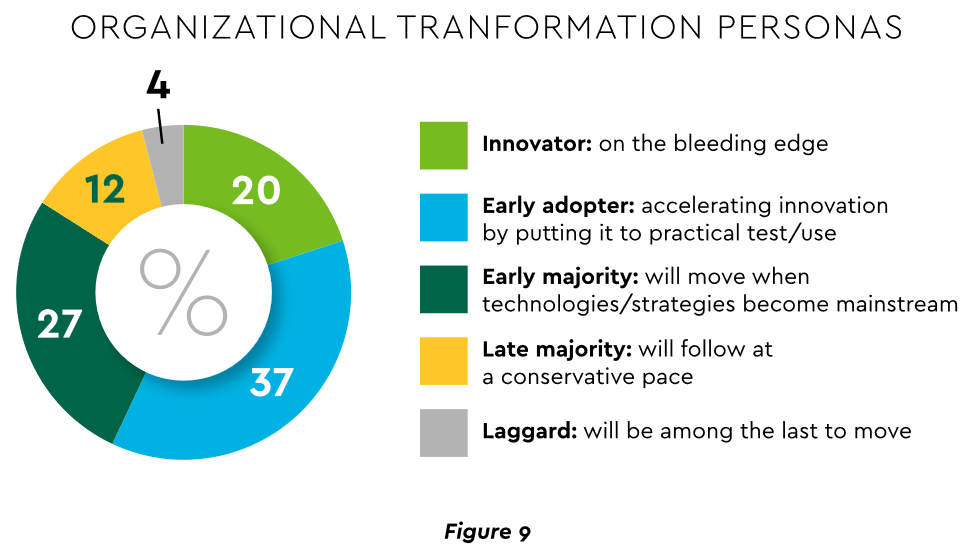

Some assert that few healthcare executives have “created digital strategies that look far enough into the future.” Speed of change is also important. Health systems, hospitals and practices exhibit varying risk appetites and change rates. When asked to self-identify “transformation personas,” a little over half regarded themselves as being on the innovative “early mover” end of the spectrum, while the remainder will adapt as technologies prove themselves (Figure 9). Slower organizations will likely need to increase the pace.

View PDF of Figure 9 chart[PDF]

Platforms, not point solutions

Implementing enterprise platforms rather than proliferating “point solutions” is obligatory. Organizations must be “prepared to compete in the platform economy as platform-based business models have changed the way we live, work and receive care.”

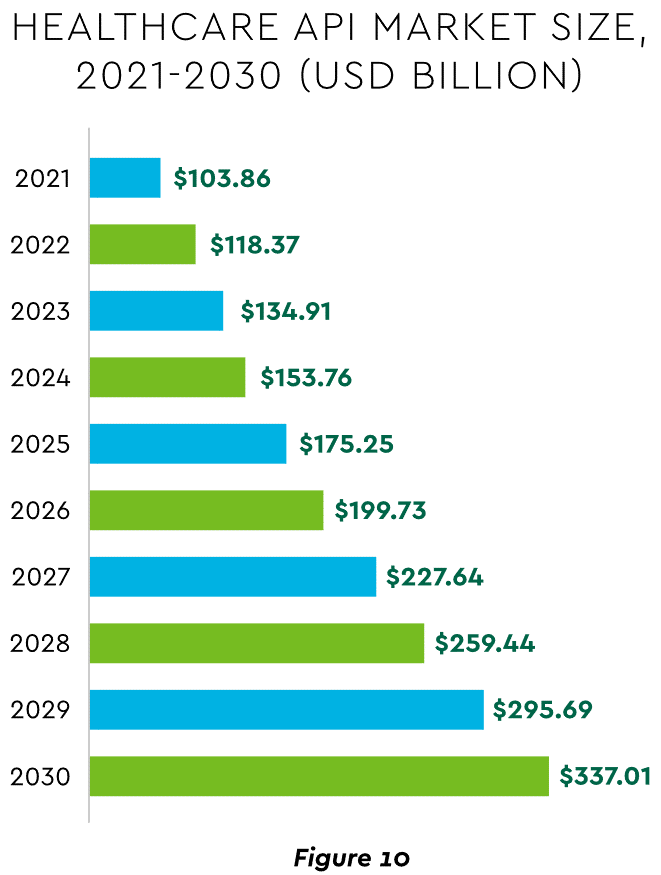

There are still too many tools and applications. A survey of top decision-makers at health systems found that 60% use over 50 software solutions just in operations (24% have over 150). System integration is one answer. Use of application programming interfaces (API) helps this effort substantially. API-first is fast becoming the norm among solution providers, with global API investment expected to nearly triple by 2030 (Figure 10)

View PDF of Figure 10 chart[PDF]

Governance

Effective governance is vital to constructing a platform-based transformative model and to ensuring wide user adoption. Healthcare has seen the rise of new senior roles such as Chief Digital Officer and Chief Transformation Officer, positions focusing on initiatives like ownership of technology success at the department level and devising user incentives.

8. Digital Payments on the Horizon for Healthcare

A variety of emerging digital payment modes will further the transformation of finance. These payments are expected to grow almost 23% annually in healthcare. ACH payments have been on a strong upward trajectory in healthcare for several years, especially for business transactions. In 2021, ACH tallied a yearly increase of 18% in volume and 5% in dollars.

Notable technologies and payment rails to watch for expected crossover from consumer markets to healthcare include:

- Mobile payments. The market for mobile payment technologies has been growing at a 16% compound annual clip and should reach $90 billion in 2023, powered by wide smartphone use, 5G networks and convenience. This category encompasses technologies such as e-wallets, forecasted to grow 23% annually worldwide through 2030.

- Real-time payments (RTP). These digital transactions are settled nearly instantaneously through platforms such as The Clearing House. One forecast sees 30.4% compound RTP growth in the U.S. from 2022 to 2030.

- Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL). This growing mode offers consumers short-term financing to stretch payments over several installments. A recent survey established that 23% of American adult respondents have used a BNPL service. BNPL is just entering healthcare and is currently regarded as an option for certain elective or cosmetic procedures or for specific individual credit scenarios.

- Earned Wage Access (EWA). Using an RTP approach, employers are beginning to offer on-demand pay which enables “instant access to earned wages right after the work is performed, at the end of the shift, or upon completion of a project.” It is not a loan or advance pay. A 2021 poll conducted by Harris found that 83% of U.S. workers feel they should be able to access earned wages at the end of each day. Millennials were particularly interested: 80% would like daily automatic pay streaming to their bank accounts, and 78% said free EWA would boost loyalty to their employer. Given its pressing workforce concerns, healthcare is likely to find EWA a tool to promote retention.

Seeking the right use cases for these payment technologies offers many potential provider benefits.

Conclusion

The connected forces discussed and quantified here create major challenges to address in 2023. The strategic agenda calls for balancing tight cost control with investment in growth opportunities, significantly enhancing patient financial experience by meeting growing patient financial need, shoring up trusted relationships and cybersecurity, and accelerating the digital transformation of finance.