Companies grappling with liquidity concerns are looking to cut costs and streamline operations, according to a new survey.

Dive Brief:

- Over three-quarters of healthcare chief financial officers expect to see profitability increases in 2024, according to a recent survey from advisory firm BDO USA. However, to become profitable, many organizations say they will have to reduce investments in underperforming service lines, or pursue mergers and acquisitions.

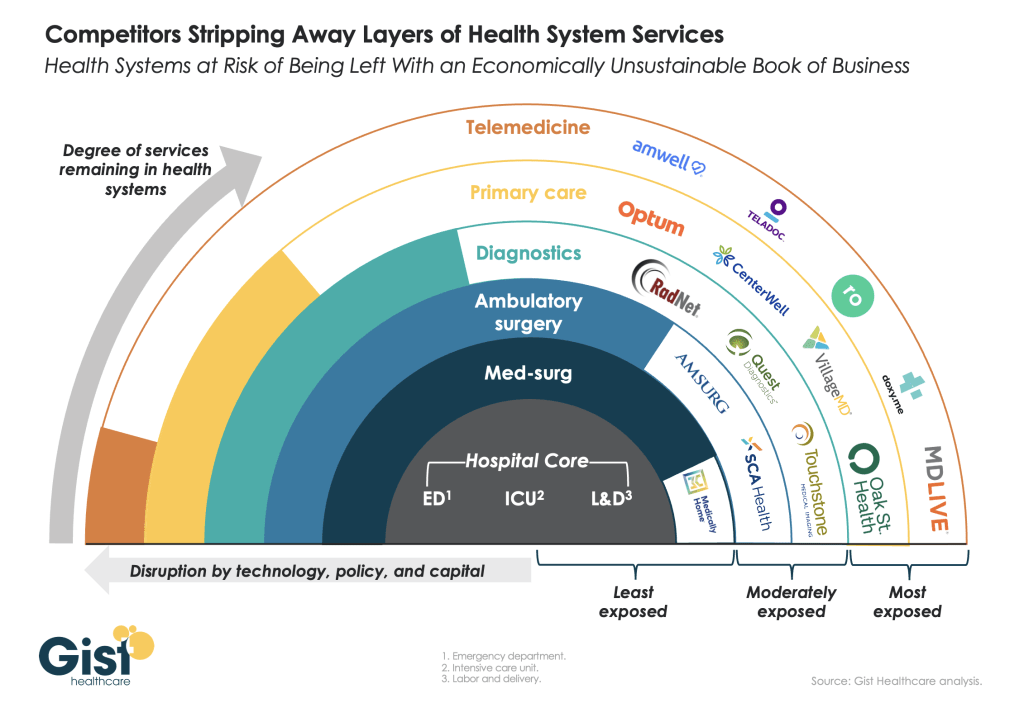

- More than 40% of respondents said they will decrease investments in primary care and behavioral health services in 2024, citing disruptions from retail players. They will shift funds to home care, ambulatory services and telehealth that provide higher returns, according to the report.

- Nearly three-quarters of healthcare CFOs plan to pursue some type of M&A deal in the year ahead, despite possible regulatory threats.

Dive Insight:

Though inflationary pressures have eased since the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare CFOs remain cognizant of managing costs amid liquidity concerns, according to the report.

The firm polled 100 healthcare CFOs serving hospitals, medical groups, outpatient services, academic centers and home health providers with revenues from $250 million to $3 billion or more in October 2023.

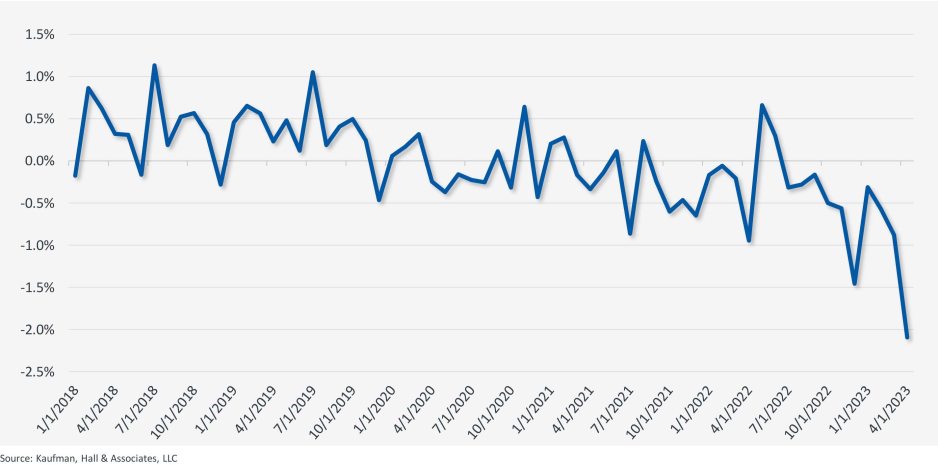

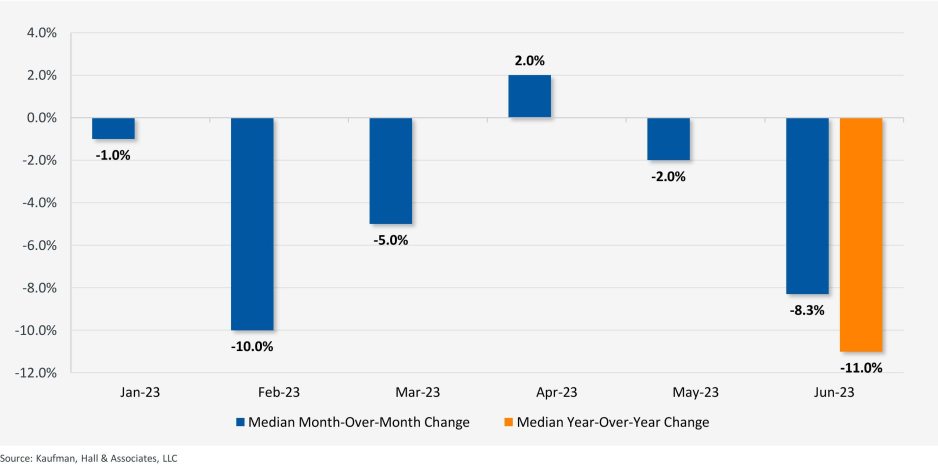

Just over a third of organizations surveyed carried more than 60 days of cash on hand. In comparison, a recent analysis from KFF found that financially strong health systems carried at least 150 days of cash on hand in 2022.

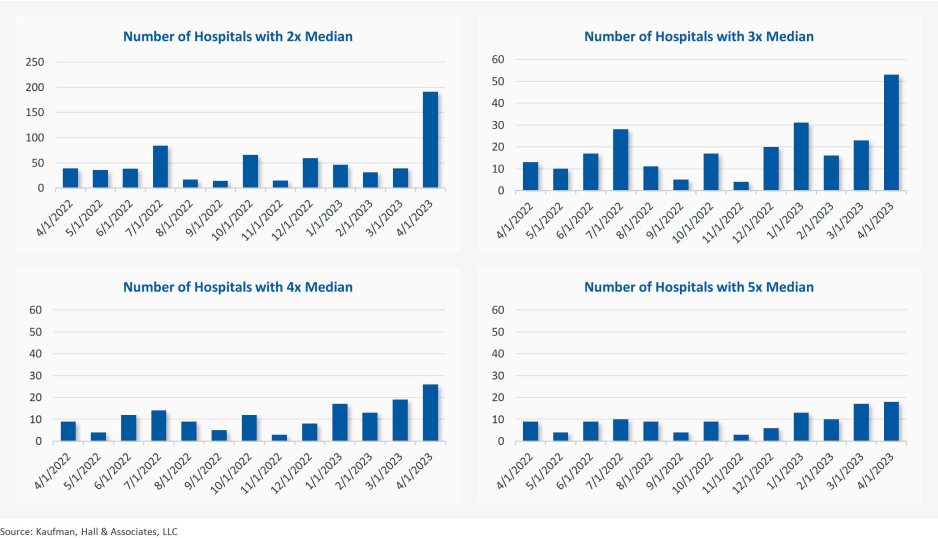

Liquidity is a concern for CFOs given high rates of bond and loan covenant violations over the past year. More than half of organizations violated such agreements in 2023, while 41% are concerned they will in 2024, according to the report.

To remain solvent, 44% of CFOs expect to have more strategic conversations about their economic resiliency in 2024, exploring external partnerships, options for service line adjustments and investments in workforce and technology optimization.

The majority of CFOs surveyed are interested in pursuing external partnerships, despite increased regulatory roadblocks, including recent merger guidance that increased oversight into nontraditional tie-ups. Last week, the FTC filed its first healthcare suit of the year to block the acquisition of two North Carolina-based Community Health Systems hospitals by Novant Health, warning the deal could reduce competition in the region.

Healthcare CFOs explore tie-ups in 2024

Types of deals that CFOs are exploring, as of Oct. 2023.

https://datawrapper.dwcdn.net/aiFBJ/1

Most organizations are interested in exploring sales, according to the report. Financially struggling organizations are among the most likely to consider deals. Nearly one in three organizations that violated their bond or loan covenants in 2023 are planning a carve-out or divestiture this year. Organizations with less than 30 days of cash on hand are also likely to consider carve-outs.

Organizations will also turn to automation to cut costs. Ninety-eight percent of organizations surveyed had piloted generative AI tools in a bid to alleviate resource and cost constraints, according to the consultancy.

“Healthcare leaders believe AI will be essential to helping clinicians operate at the top of their licenses, focusing their time on patient care and interaction over administrative or repetitive tasks,” authors wrote. Nearly one in three CFOs plan to leverage automation and AI in the next 12 months.

However, CFOs are keeping an eye on the risks. As more data flows through their organizations, they are increasingly concerned about cybersecurity. More than half of executives surveyed said data breaches are a bigger risk in 2024 compared to 2023.