Like everyone else, I am thankful the election end is in sight and a degree of “normalcy” might return. By next week, we should know who will sit in the White House, the 119th Congress and 11 new occupants of Governors’ offices. But a return to pre-election normalcy in politics is a mixed blessing.

“Normalcy” in our political system means willful acceptance that our society is hopelessly divided by income, education, ethnic and political views. It’s benign acceptance of a 2-party system, 3-branches of government (Executive, Legislative, Judicial) and federalism that imposes limits on federal power vis a vis the Constitution.

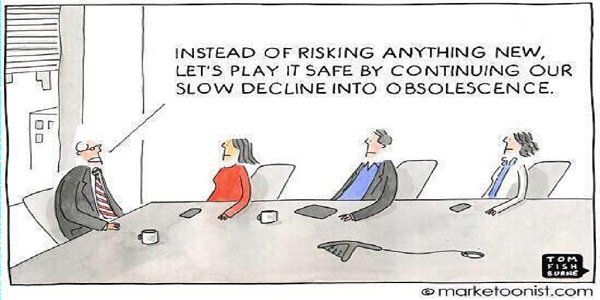

Our political system’ normalcy counts success by tribal warfare and election wins. Normalcy is about issues de jour prioritized by each tribe, not longer-term concern for the greater good in our country. Normalcy in our political system is near-sightedness—winning the next election and controlling public funds.

Comparatively, “normalcy” in U.S. healthcare is also tribal:

while the majority of U.S. adults believe the status quo is not working well but recognize its importance, each tribe has a different take on its future. The majority of the public think price transparency, limits on consolidation, attention to affordability and equitable access are needed but the major tribes—hospitals, insurers, drug companies, insurers, device-makers—disagree on how changes should be made. And each is focused on short-term issues of interest to their members with rare attention to longer-term issues impacting all.

Near-sightedness in healthcare is manifest in how executives are compensated, how partnerships are formed and how Boards are composed.

Organizational success is defined by 1-access to private capital (debt, private equity, strategic investors), 2-sustainnable revenue-growth, 4- scalable costs, 4-opportunities for consolidation (the exit strategy of choice for most) and 5-quarterly earnings. A long-term view of the system’s future is rarely deliberated by boards save attention to AI or the emergence of Big Tech. A vision for an organization’s future based on long-term macro-trends and outside-in methodologies is rare: long-term preparedness is “appreciated” but near-term performance is where attention is vested.

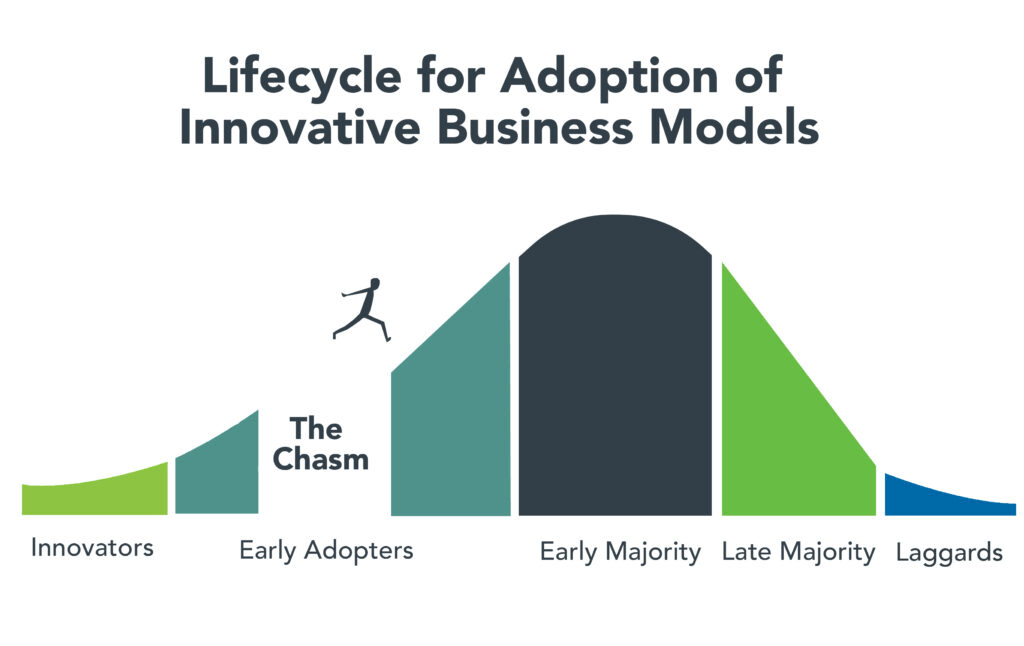

It pays to be near-sighted in healthcare: our complex regulatory processes keep unwelcome change at bay and our archaic workforce rules assure change resistance. …until it doesn’t. Industries like higher education, banking and retailing have experienced transformational changes that take advantage of new technologies and consumer appetite for alternatives that are new and better. The organizations winning in this environment balance near-sightedness with market attentiveness and vision.

Looking ahead, I have no idea who the winners and losers will be in this election cycle. I know, for sure, that…

- The final result will not be known tomorrow and losers will challenge the results.

- Short-term threats to the healthcare status quo will be settled quickly. First up: Congress will set aside Medicare pay cuts to physicians (2.8%) scheduled to take effect in January for the 5th consecutive year. And “temporary” solutions to extend marketplace insurance subsidies, facilitate state supervision of medication abortion services and telehealth access will follow quickly.

- Think tanks will be busy producing white papers on policy changes supported by their funding sponsors.

- And trade associations will produce their playbooks prioritizing legislative priorities and relationship opportunities with state and federal officials for their lobbyists.

Near-term issues for each tribe will get attention: the same is true in healthcare. Discussion about and preparation for healthcare’s longer-term future is a rarity in most healthcare C suites and Boardrooms. Consider these possibilities:

- Medicare Advantage will be the primary payer for senior health: federal regulators will tighten coverage, network adequacy, premiums and cost sharing with enrollees to private insurers reducing enrollee choices and insurer profits.

- To address social determinants of health, equitable access and comprehensive population health needs, regional primary care, preventive and public health programs will be fully integrated.

- Large, organized groups/networks of physicians will be the preferred “hubs” for health services in most markets.

- Interoperability will be fully implemented.

- Physicians will unionize to assert their clinical autonomy and advance their economic interests.

- The federal government (and some states) will limit tax exemptions for profitable not-for-profit health systems.

- The prescription drug patent system will be modernized to expedite time-to-market innovations and price-value determinations.

- The health insurance market will focus on individual (not group) coverage.

- Congress/states will impose price controls on prescription drugs and hospital services.

- Employers will significantly alter their employee benefits programs to reduce their costs and shift accountability to their employees. Many will exit altogether.

- Regional integrated health systems that provide retail, hospital, physician, public health and health insurance services will be the dominant source of services.

- Alternative-payment models used by Medicare to contract with providers will be completely overhauled.

- Consumers will own and control their own medical records.

- Consolidation premised on community benefits, consumer choices and lower costs will be challenged aggressively and reparation pursued in court actions.

- Voters will pass Medicare for All legislation.

And many others.

A process for defining of the future of the U.S. health system and a bipartisan commitment by hospitals, physicians, drug companies, insurers and employers to its implementation are needed–that’s the point.

Near-sightedness in our political system and in our health, system is harmful to the greater good of our society and to the voters, citizens, patients, and beneficiaries all pledge to serve.

As respected healthcare marketer David Jarrard wrote in his blog post yesterday “As the aggravated disunity of this political season rises and falls, healthcare can be a unique convener that embraces people across the political divides, real or imagined. Invite good-minded people to the common ground of healthcare to work together for the common good that healthcare must be.”

Thinking and planning for healthcare’s long-term future is not a luxury: it’s an urgent necessity. It’s also not “normal” in our political and healthcare systems.