Graphic of the Day: Citizens Who Lost Healthcare Coverage Since the Pandemic Began

People of color are far more likely to worry about their ability to pay for healthcare if they are diagnosed with COVID-19 than their white counterparts, according to a new survey from nonprofit West Health and Gallup.

By a margin of almost two to one (58% vs. 32%), nonwhite adults report that they are either “extremely concerned” or “concerned” about the potential cost of care. That concern is three times higher among lower-income than higher-income households (60% vs. 20%).

The data come from an ongoing survey about Americans’ experiences with and attitudes about the healthcare system. The latest findings are based on a nationally representative sample of 1,017 U.S. adults interviewed between June 8 and June 30.

There’s also a disturbing trend when it comes to medication insecurity. Overall, 24% of U.S. adults say they lacked money to pay for at least one prescribed medicine in the past 12 months, an increase from 19% in early 2019. Among nonwhite Americans, the burden is growing even more quickly. Medication insecurity jumped 10 percentage points, from 21% to 31%, compared with a statistically insignificant three-point increase among white Americans (17% to 20%).

WHAT’S THE IMPACT?

All of this results in what Tim Lash, chief strategy officer for West Health, called a “significant and increasing racial and socioeconomic divide” in Americans’ views on the cost of healthcare and the impact it has on their lives. When polling started in 2019, one in five Americans were unable to pay for prescription medications within the past 12 months. That number now stands at one in four. The bottom line is that the situation is getting worse.

Amid broad concern about paying for the cost of COVID-19 or other medical expenses, health insurance benefits are likely more important than ever to U.S. workers. The survey found that 12% of workers are staying in a job they want to leave because they are afraid of losing healthcare benefits, a sentiment that is about twice as likely to be held by nonwhite workers as white workers (17% vs. 9%).

However, Americans step across racial lines in their overwhelming support for disallowing political contributions by pharmaceutical companies, and for government intervention in setting price limits for government-sponsored research and a COVID vaccine.

Nearly 9 in 10 U.S. adults (89%) think the federal government should be able to negotiate the cost of a COVID-19 vaccine, while only 10% say the drug company itself should set the price. Similarly, 86% of U.S. adults say there should be limits on the price of drugs that government-funded research helped develop.

Regarding the influence of pharmaceutical companies on the political process, 78% of adults say political campaigns should not be allowed to accept donations from pharmaceutical companies during the coronavirus pandemic.

THE LARGER TREND

Concerns over payment aren’t the only race-related disparities found in healthcare. Dr. Garth Graham, the vice president of community health at CVS Health, said during AHIP’s Institute and Expo in June that although African Americans make up 13% of the U.S. population, they account for about 24% of COVID-19 deaths.

He attributed some of the driving factors for these particular COVID-19-related disparities to the social determinants of health, the over-predominance of African American and Latino frontline workers, and the higher incidence-rates of chronic illness such as diabetes and hypertension in minority groups.

On June 19 – Juneteenth, as it’s known for many Black Americans – 36 Chicago hospitals penned an open letter declaring that systemic racism is a “public health crisis.”

“Systemic racism is a real threat to the health of our patients, families and communities,” the letter reads. “We stand with all of those who have raised their voices to capture the attention of Chicago and the nation with a clear call for action.”

https://mailchi.mp/0fa09872586c/the-weekly-gist-july-31-2020?e=d1e747d2d8

After a week that brought the most disastrous economic data in modern history, the death of a former Presidential candidate from COVID, and signs of an alarming surge in virus cases in the Midwest, Congress left Washington for the weekend without reaching a deal on a new recovery bill. That left millions of unemployed Americans without supplemental benefit payments, business owners wondering whether more financial assistance would be forthcoming, and hospitals facing the requirement to begin repaying billions of dollars of advance payments from Medicare.

Also remaining on the table was funding to bolster coronavirus testing, with the top health official in charge of the testing effort testifying on Friday that the system is not currently able to deliver COVID test results to patients in a timely manner. While the surge in cases appears to be shifting to the Midwest, there were early indications of positive news across the Sun Belt, as the daily new case count in Florida, Louisiana, Texas, Arizona and California continued to decline, while daily death counts (a lagging indicator) continued to hit new records.

Nationally, the daily case count appears to have reached a new plateau of around 65,000, with daily deaths rising to a 7-day average above 1,150, matching a level last seen in May.

Meanwhile, new clinical findings continued to refine our understanding of how the virus attacks its victims. Reporting in JAMA Cardiology, researchers used cardiac MRI to examine heart function among 100 coronavirus patients, 67 of whom recovered at home without hospitalization, finding that 78 percent demonstrated cardiac involvement and 60 percent had evidence of active heart muscle inflammation—concerning signs pointing to possible long-term complications, even in patients with relatively mild courses of COVID infection.

And yesterday in JAMA, investigators reported that while young children are typically less affected by COVID-19 than adults, children under 5 may harbor 100 times as much active virus in their nose and throat as infected adults. While the study does not confirm that kids spread the virus to adults, it is sure to raise concerns about reopening schools, which has generally been considered relatively safer for younger children.

US coronavirus update: 4.8M cases; 151K deaths; 52.9M tests conducted.

The coronavirus pandemic hit the nation hard and fast, infecting Americans from coast to coast, overwhelming health care systems and wreaking havoc on the economy. Those with pre-existing conditions – like diabetes and cardiovascular disease – are more vulnerable to the deadly virus. Americans have higher rates of these chronic conditions than other countries, in part because so many people live without health insurance or have shoddy coverage. This has become increasingly worse over the last four years as underlying health coverage has shrunken for the virus’s hardest hit victims: Black Americans, Native Americans and people of color.

Of the hundreds of thousands of Americans now recovering from COVID-19, many will undoubtedly have new chronic conditions, like lasting lung damage. This will be on top of the pre-existing conditions many who were predisposed to coronavirus already had. Record job losses in the wake of the pandemic have resulted in the loss of employer-sponsored coverage for more than 5 million Americans who are now on the hunt for new, affordable health insurance plans.

This presents the perfect storm for junk insurance plans – short-term limited duration insurance plans – that allow discrimination based on pre-existing conditions, expose consumers to financial risk and provide inadequate coverage. STLDIs are more dangerous now than ever in our new COVID-19 reality. Let’s be clear: These junk insurance plans – touted by the Trump administration and supported through taxpayer dollars – are not the answer. It is time for our leaders to put back the limitations on how long they can be used.

As their name suggests, short-term limited duration plans are meant to be used temporarily to bridge short-term gaps in coverage that arise from a job loss or other extenuating circumstance. However, new federal rules under the Trump administration have allowed the coverage period of STLDI plans to expand from six to 12 months. The administration has also promoted these plans to states as being eligible for federal subsidies, meaning our tax dollars help pay for them. President Donald Trump himself has touted these plans for being more affordable than Obamacare, but that is because they lack the same protections and do not meet minimum essential coverage standards under the law.

That is what makes these plans so dangerous. Though they tend to be less expensive than Affordable Care Act plans, they leave consumers vulnerable to unanticipated out-of-pocket costs by offering bare-bones coverage. Unlike ACA plans, STLDI plans can exclude coverage for pre-existing conditions, do not cover the cost of prescription drugs, have annual or lifetime maximums on covered services, and are not required to cover preventive services like cancer screenings or maternity care.

The lower price tag may lure consumers suffering financially during the pandemic, but they are high risk for those who do not fully understand what they are buying. Without carefully reading the fine print, many may not know before purchasing that STLDI plans are exempt from ACA rules as well as regulations for insurers recently passed in the Families First Coronavirus Response Act and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act. We have already seen the pandemic exacerbate existing health inequalities in America, and now these plans expose consumers, especially low-income individuals and those with chronic conditions, to more discrimination and financial ruin.

The Department of Health and Human Services has already acknowledged that these plans fall short. In fact, the government is having to cover the cost of COVID-19 testing for people with STLDI plans, classifying them as “uninsured.” Yet, they will not cover the cost of COVID-19 treatment, meaning those with STLDI plans could face bills in the thousands of dollars, considering the average cost to treat a hospitalized coronavirus patient is $30,000.

Consumers for Quality Care, a coalition of advocates and former policy makers which provides a voice for patients in the health care debate, recently sent a letter to HHS Secretary Alex Azar and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Administrator Seema Verma asking that they protect consumers from these dangerous plans.

This pandemic has laid bare how dangerously unprepared America’s health care system is for a large-scale public health crisis. People needed high-quality insurance coverage before coronavirus hit, and they will need it long after the pandemic subsides. Let this be a lesson to the Trump administration – it is time to stop backing junk insurance plans and remove them from the open market. If our leaders fail to act, the lives and financial well-being of millions of Americans are at stake.

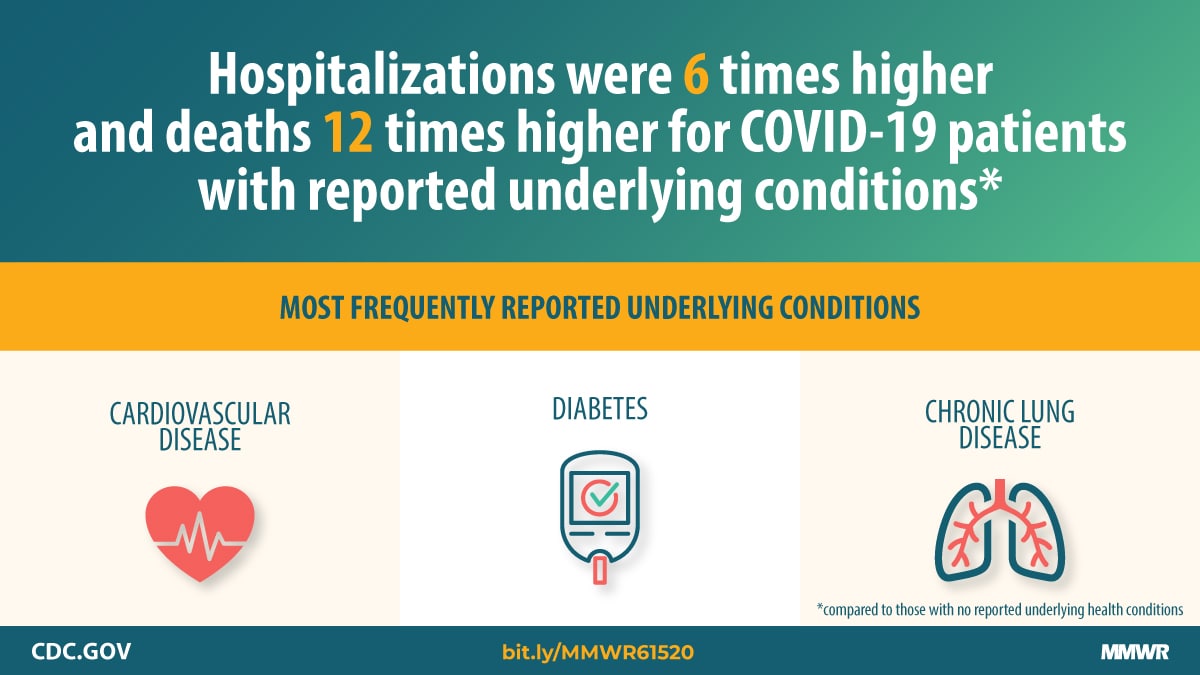

About 47% of US adults have an underlying condition strongly tied to severe COVID-19 illness, researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have found.

The model-based study, published today in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, used self-reported data from the 2018 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System and the US Census.

Researchers analyzed the data for the prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), heart disease, diabetes, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and obesity in residents of 3,142 counties in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. They defined obesity as having a body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m2 or higher.

They found that prevalence patterns generally followed population distributions, with high numbers in large cities, but that these conditions were more prevalent in rural than in urban areas. Counties with the highest prevalence of these conditions were generally clustered in the Southeast and Appalachia.

Severe COVID-19 disease, requiring hospitalization, intensive care, and mechanical ventilation or leading to death, is most common in people of advanced age and in those who have at least one of the previously mentioned underlying conditions.

A CDC analysis last month of US COVID-19 patient surveillance data from Jan 22 to May 30 showed that those with underlying conditions were hospitalized six times more often, needed intensive care five times more often, and had a death rate 12 times higher than those without these conditions. But the authors of today’s reported noted that the earlier study defined obesity as a BMI of 40 kg/m2 or higher and included some conditions with mixed or limited evidence of a tie to poor coronavirus outcomes.

Median estimated county prevalence of any underlying illness was 47.2% (range, 22.0% to 66.2%). Numbers of people with any underlying condition ranged from 4,300 in rural counties to 301,744 in large cities.

Prevalence of obesity was 35.4% (range, 15.2% to 49.9%), while it was 12.8% for diabetes (range, 6.1% to 25.6%), 8.9% for COPD (range, 3.5% to 19.9%), 8.6% for heart disease (range, 3.5% to 15.1%), and 3.4% for CKD, 3.4% (range, 1.8% to 6.2%).

Nationwide, the overall weighted prevalence of adults with chronic underlying conditions was 30.9% for obesity, 11.4% for diabetes, 6.9% for COPD, 6.8% for heart disease, and 3.1% for CKD.

The estimated median prevalence of any underlying condition generally increased with increasing county remoteness, ranging from 39.4% in large metropolitan counties to 48.8% in rural ones.

The authors noted that access to healthcare resources in some rural counties may be poor, adding to the risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes.

“The findings can help local decision-makers identify areas at higher risk for severe COVID-19 illness in their jurisdictions and guide resource allocation and implementation of community mitigation strategies,” they wrote. “These findings also emphasize the importance of prevention efforts to reduce the prevalence of these underlying medical conditions and their risk factors such as smoking, unhealthy diet, and lack of physical activity.”

The researchers called for future studies to include the weighting of the contribution of each underlying illness according to the risk of serious COVID-19 outcomes and identifying and integrating other factors leading to susceptibility to both infection and serious outcomes to better estimate the number of people at increased risk for COVID-19 infection.

Dr. Anne Peters splits her mostly virtual workweek between a diabetes clinic on the west side of Los Angeles and one on the east side of the sprawling city.

Three days a week she treats people whose diabetes is well-controlled. They have insurance, so they can afford the newest medications and blood monitoring devices. They can exercise and eat well. Those generally more affluent West L.A. patients who have gotten COVID-19 have developed mild to moderate symptoms – feeling miserable, she said – but treatable, with close follow-up at home.

“By all rights they should do much worse, and yet most don’t even go to the hospital,” said Peters, director of the USC Clinical Diabetes Programs.

On the other two days of her workweek, it’s a different story.

In East L.A., many patients didn’t have insurance even before the pandemic. Now, with widespread layoffs, even fewer do. They live in “food deserts,” lacking a car or gas money to reach a grocery store stocked with fresh fruits and vegetables. They can’t stay home, because they’re essential workers in grocery stores, health care facilities and delivery services. And they live in multi-generational homes, so even if older people stay put, they are likely to be infected by a younger relative who can’t.

They tend to get COVID-19 more often and do worse if they get sick, with more symptoms and a higher likelihood of ending up in the hospital or dying, said Peters, also a member of the leadership council of Beyond Type 1, a diabetes research and advocacy organization.

“It doesn’t mean my East Side patients are all doomed,” she emphasized.

But it does suggest COVID-19 has an unequal impact, striking people who are poor and already in ill health far harder than healthier, better off people on the other side of town.

Tracey Brown has known that for years.

“What the COVID-19 pandemic has done is shined a very bright light on this existing and pervasive problem,” said Brown, CEO of the American Diabetes Association. Along with about 32 million others – roughly 1 in 10 Americans – Brown has diabetes herself.

“We’re in 2020, and every 5 minutes, someone is losing a limb” to diabetes, she said. “Every 10 minutes, somebody is having kidney failure.”

Americans with diabetes and related health conditions are 12 times more likely to die of COVID-19 than those without such conditions, she said. Roughly 90% of Americans who die of COVID-19 have diabetes or other underlying conditions. And people of color are over-represented among the very sick and the dead.

The data is clear: People with diabetes are at increased risk of having a bad case of COVID-19, and diabetics with poorly controlled blood sugar are at even higher risk, said Liam Smeeth, dean of the faculty of epidemiology and population health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. He and his colleagues combed data on 17 million people in the U.K. to come to their conclusions.

Diabetes often comes paired with other health problems – obesity and high blood pressure, for instance. Add smoking, Smeeth said, and “for someone with diabetes in particular, those can really mount up.”

People with diabetes are more vulnerable to many types infections, Peters said, because their white blood cells don’t work as well when blood sugar levels are high.

“In a test tube, you can see the infection-fighting cells working less well if the sugars are higher,” she said.

Peters recently saw a patient whose diabetes was triggered by COVID-19, a finding supported by one recent study.

Going into the hospital with any viral illness can trigger a spike in blood sugar, whether someone has diabetes or not. Some medications used to treat serious cases of COVID-19 can “shoot your sugars up,” Peters said.

In patients who catch COVID-19 but aren’t hospitalized, Peters said, she often has to reduce their insulin to compensate for the fact that they aren’t eating as much.

Low income seems to be a risk factor for a bad case of COVID-19, even independent of age, weight, blood pressure and blood sugar levels, Smeeth said. “We see strong links with poverty.”

Some of that is driven by occupational risks, with poorer people unable to work from home or avoid high-risk jobs. Some is related to housing conditions and crowding into apartments to save money. And some, may be related to underlying health conditions.

But the connection, he said, is unmistakable.

Peters recently watched a longtime friend lose her husband. Age 60 and diabetic, he was laid off due to COVID, which cost him his health insurance. He developed a foot ulcer that he couldn’t afford to treat. He ignored it until he couldn’t stand anymore and then went to the hospital.

After surgery, he was released to a rehabilitation facility where he contracted COVID. He was transferred back to the hospital, where he died four days later.

“He died, not because of COVID and not because of diabetes, but because he didn’t have access to health care when he needed it to prevent that whole process from happening,” Peters said, adding that he couldn’t see his family in his final days and died alone. “It just breaks your heart.”

Now is a great time to improve diabetes control, Peters added. With many restaurants and most bars closed, people can have more control over what they eat. No commuting leaves more time for exercise.

That’s what David Miller has managed to do. Miller, 65, of Austin, Texas, said he has stepped up his exercise routine, walking for 40 minutes four mornings a week at a nearby high school track. It’s cool enough at that hour, and the track’s not crowded, said Miller, an insurance agent, who has been able to work from home during the pandemic. “That’s more consistent exercise than I’ve ever done.”

His blood sugar is still not where he wants it to be, he said, but his new fitness routine has helped him lose a little weight and bring his blood sugar under better control. Eating less remains a challenge. “I’m one of those middle-aged guys who’s gotten into the habit of eating for two,” he said. “That can be a hard habit to shake.”

Miller said he isn’t too worried about getting COVID-19.

“I’ve tried to limit my exposure within reason,” he said, noting that he wears a mask when he can in public. “I honestly don’t feel particularly more vulnerable than anybody else.”

Smeeth, the British epidemiologist, said even though they’re at higher risk for bad outcomes, people with diabetes should know that they’re not helpless.

“The traditional public health messages – don’t be overweight, give up smoking, keep active – are still valid for COVID,” he said. Plus, people with diabetes should prioritize getting a flu vaccine this fall, he said, to avoid compounding their risk.

(For more practical recommendations for those living with diabetes during the pandemic, go to coronavirusdiabetes.org.)

In Los Angeles, Peters said, the county has made access to diabetes medication much easier for people with low incomes. They can now get three months of medication, instead of only one. “We refill everybody’s medicine that we can to make sure people have the tools,” she said, adding that diabetes advocates are also doing what they can to help people get health insurance.

Controlling blood sugar will help everyone, not just those with diabetes, Peters said. Someone hospitalized with uncontrolled blood sugar takes up a bed that could otherwise be used for a COVID-19 patient.

Brown, of the American Diabetes Association, has been advocating for those measures on a national level, as well as ramping up testing in low-income communities. Right now, most testing centers are in wealthier neighborhoods, she said, and many are drive-thrus, assuming that everyone who needs testing has a car.

Her organization is also lobbying for continuity of health insurance coverage if someone with diabetes loses their job, as well as legislation to remove co-pays for diabetes medication.

“The last thing we want to have happen is that during this economically challenged time, people start rationing or skipping their doses of insulin or other prescription drugs,” Brown said. That leads to unmanaged diabetes and complications like ulcers and amputations. “Diabetes is one of those diseases where you can control it. You shouldn’t have to suffer and you shouldn’t have to die.”

Elective procedures are in a strange place at the moment. When the COVID-19 pandemic started to ramp up in the U.S., many of the nation’s hospitals decided to temporarily cancel elective surgeries and procedures, instead dedicating the majority of their resources to treating coronavirus patients. Some hospitals have resumed these surgeries; others resumed them and re-cancelled them; and still others are wondering when they can resume them at all.

In a recent HIMSS20 digital presentation, Reenita Das, a senior vice president and partner at Frost and Sullivan, said that during the pandemic, plastic surgery activity declined by 100%, ENT surgeries declined by 79%, cardiovascular surgeries declined by 53% and neurosurgery surgeries declined by 57%.

It’s hard to overstate the financial impact this is likely to have on hospitals’ bottom lines. Just this week, American Hospital Association President and CEO Rick Pollack, pulling from Kaufman Hall data, said the cancellation of elective surgeries is among the factors contributing to a likely industry-wide loss of $120 billion from July to December alone. When including data from earlier in the pandemic, the losses are expected to be in the vicinity of $323 billion, and half of the nation’s hospitals are expected to be in the red by the end of the year.

Doug Wolfe, cofounder and managing partner of Miami-based law firm Wolfe Pincavage, said this has amounted to a “double-whammy” for hospitals, because on top of elective procedures being cancelled, the money healthcare facilities received from the federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act was an advance on future Medicare payments – which is coming due. While hospitals perform fewer procedures, they will now have to start paying that money back.

All hospitals are hurting, but some are in a more precarious position than others.

“Some hospital systems have had more cash on hand and more liquidity to withstand some of the financial pressure some systems are facing,” said Wolfe. “Traditionally, the smaller hospital systems in the healthcare climate we face today have faced a lot more financial pressure. They’re not able to control costs the same way as a big system. The smaller hospitals and systems were hurting to begin with.”

LOWER REVENUE, HIGHER COSTS

Some hospitals, especially ones in hot spots, are seeing a surge in COVID-19 patients. While this has kept frontline healthcare workers scrambling to care for scores of sick Americans, COVID-19 treatments are not reimbursed at the same level as surgeries. Hospital capacity is being stretched with less lucrative services.

“Some hospitals may be filling up right now, but they’re filling up with lower-reimbursing volume,” said Wolfe. “Inpatient stuff is lower reimbursement. It’s really the perfect storm for hospitals.”

John Haupert, CEO of Grady Health in Atlanta, Georgia, said this week that COVID-19 has had about a $115 million negative impact on Grady’s bottom line. Some $70 million of that is related to the reduction in the number of elective surgeries performed, as well as dips in emergency department and ambulatory visits.

During one week in March, Grady saw a 50% reduction in surgeries and a 38% reduction in ER visits. The system is almost back to even in terms of elective and essential surgeries, but due to a COVID-19 surge currently taking place in Georgia, it has had to suspend those services once again. ER visits have only come back about halfway from that initial 38% dip, and the system is currently operating at 105% occupancy.

“Part of what we’re seeing there is reluctance from patients to come to hospitals or seek services,” said Haupert. “Many have significantly exacerbated chronic disease conditions.”

Patient hesitation has been an ongoing problem, as has the associated cost of treating coronavirus patients, said Wolfe.

“When they were ramping up to resume the elective stuff, there was a problem getting patients comfortable,” he said. “And the other thing was that the cost of treating patients in this environment has gone up. They’ve put up plexiglass everywhere, they have more wiping-down procedures, and all of these things add cost and time. They need to add more time between procedures so they can clean everything … so they’re able to do less, and it costs more to do less. Even when elective procedures do resume, it’s not going back to the way it was.”

Most hospitals have adjusted their costs to mitigate some of the financial hit. Even some larger systems, such as 92-hospital nonprofit Trinity Health in Michigan, have taken to measures such as laying off and furloughing workers and scaling back working hours for some of its staff. At the top of the month, Trinity announced another round of layoffs and furloughs – in addition to the 2,500 furloughs it announced in April – citing a projected $2 billion in revenue losses in fiscal year 2021, which began on June 1.

Hospitals are at the mercy of the market at the moment, and Wolfe anticipates there could be an uptick in mergers and consolidation as organizations look to partner with less cash-strapped entities.

“Whether reorganization will work remains to be seen, but there will definitely be a fallout from this,” he said.

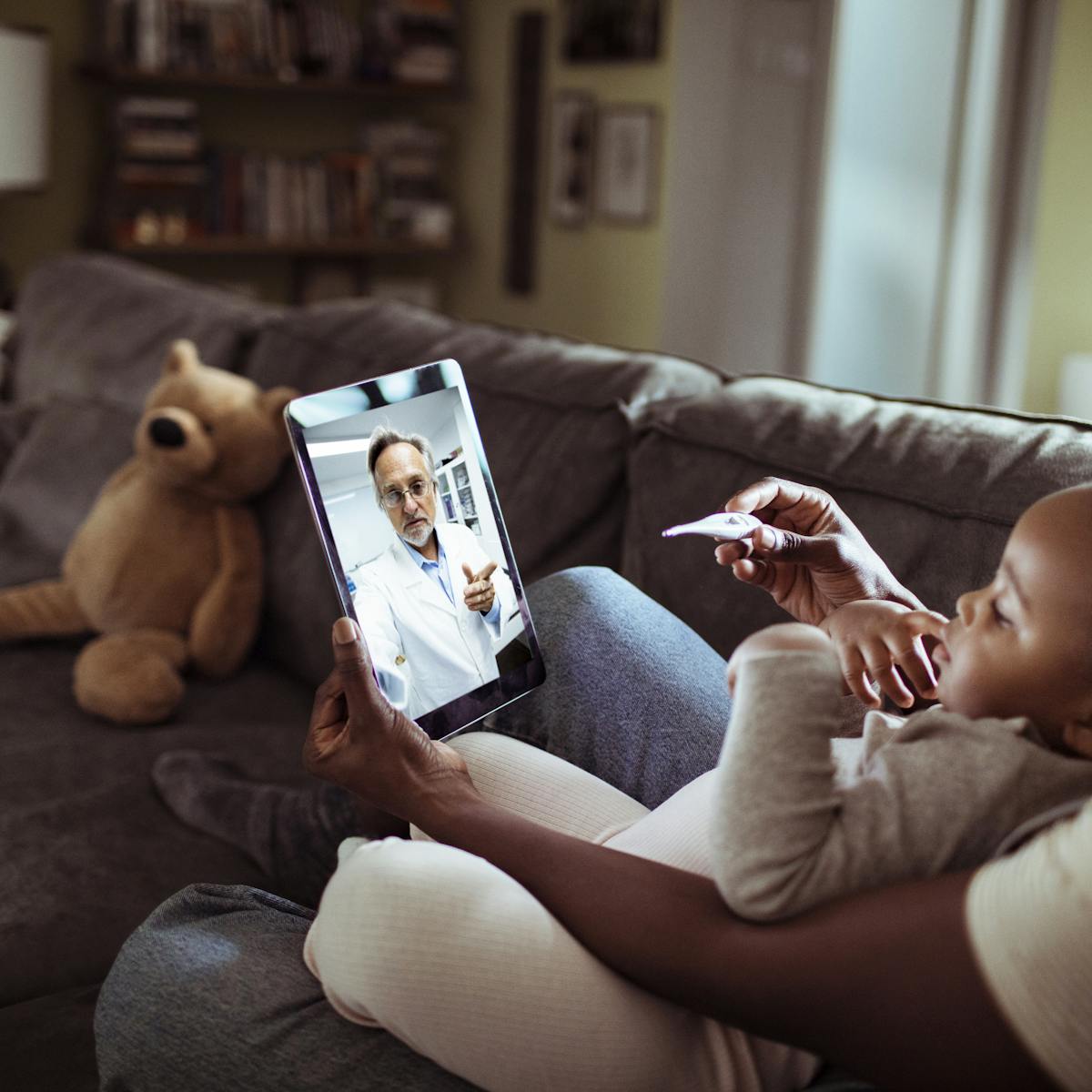

COVID-19 has led to a boom in telehealth, with some health care facilities seeing an increase in its use by as much as 8,000%.

This shift happened quickly and unexpectedly and has left many people asking whether telehealth is really as good as in-person care.

Over the last decade, I’ve studied telehealth as a Ph.D. researcher while using it as a registered nurse and advanced practice nurse. Telehealth is the use of phone, video, internet and technology to perform health care, and when done right, it can be just as effective as in-person health care. But as many patients and health care professionals switch to telehealth for the first time, there will inevitably be a learning curve as people adapt to this new system.

So how does a patient or a provider make sure they are using telehealth in the right way? That is a question of the technology available, the patient’s medical situation and the risks of going – or not going – to a health care office.

There are three main types of telehealth: synchronous, asynchronous and remote monitoring. Knowing when to use each one – and having the right technology on hand – is critical to using telehealth wisely.

Synchronous telehealth is a live, two-way interaction, usually over video or phone. Health care providers generally prefer video conferencing over phone calls because aside from tasks that require physical touch, nearly anything that can be done in person can be done over video. But some things, like the taking of blood samples, for example, simply cannot be done over video.

Many of the limitations of video conferencing can be overcome with the second telehealth approach, remote patient monitoring. Patients can use devices at home to get objective data that is automatically uploaded to health care providers. Devices exist to measure blood pressure, temperature, heart rhythms and many other aspects of health. These devices are great for getting reliable data that can show trends over time. Researchers have shown that remote monitoring approaches are as effective as – and in some cases better than – in-person care for many chronic conditions.

Some remaining gaps can be filled with the third type, asynchronous telehealth. Patients and providers can use the internet to answer questions, describe symptoms, refill prescription refills, make appointments and for other general communication.

Unfortunately, not every provider or patient has the technology or the experience to use live video conferencing or remote monitoring equipment. But even having all the available telehealth technology does not mean that telehealth can solve every problem.

Generally, telehealth is right for patients who have ongoing conditions or who need an initial evaluation of a sudden illness.

Because telehealth makes it easier to have have frequent check-ins compared to in-person care, managing ongoing care for chronic illnesses like diabetes, heart disease and lung disease can be as safe as or better than in-person care.

Research has shown that it can also be used effectively to diagnose and even treat new and short-term health issues as well. The tricky part is knowing which situations can be dealt with remotely.

Imagine you took a fall and want to get medical advice to make sure you didn’t break your arm. If you were to go to a hospital or clinic, almost always, the first health care professional you’d see is a primary care generalist, like me. That person will, if possible, diagnose the problem and give you basic medical advice: “You’ve got a large bruise, but nothing appears to be broken. Just rest, put some ice on it and take a pain reliever.” If I look at your arm and think you need more involved care, I would recommend the next steps you should take: “Your arm looks like it might be fractured. Let’s order you an X-ray.”

This first interaction can easily be done from home using telehealth. If a patient needs further care, they would simply leave home to get it after meeting with me via video. If they don’t need further care, then telehealth just saved a lot of time and hassle for the patient.

Research has shown that using telehealth for things like minor injuries, stomach pains and nausea provides the same level of care as in-person medicine and reduces unnecessary ambulance rides and hospital visits.

Some research has shown that telehealth is not as effective as in-person care at diagnosing the causes of sore throats and respiratory infections. Especially now during the coronavirus pandemic, in-person care might be necessary if you are having respiratory issues.

And finally, for obviously life-threatening situations like severe bleeding, chest pain or shortness of breath, patients should still go to hospitals and emergency rooms.

With the right technology and in the right situations, telehealth is an incredibly effective tool. But the question of when to use telehealth must also take into account the risk and burden of getting care.

COVID-19 increases the risks of in-person care, so while you should obviously still go to a hospital if you think you may be having a heart attack, right now, it might be better to have a telehealth consultation about acne – even if you might prefer an in-person appointment.

Burden is another thing to consider. Time off work, travel, wait times and the many other inconveniences that go along with an in-person visit aren’t necessary simply to get refills for ongoing medication. But, if a provider needs to draw a patient’s blood to monitor the safety or effectiveness of a prescription medicine, the burden of an in-person visit to the lab is likely worth the increased risk.

Of course, not all health care can be done by telehealth, but a lot can, and research shows that in many cases, it’s just as good as in-person care. As the pandemic continues and other problems need addressing, think about the right telehealth fit for you, and talk to your health care team about the services offered, your risks and your preferences. You might find that that there are far fewer waiting rooms in your future.

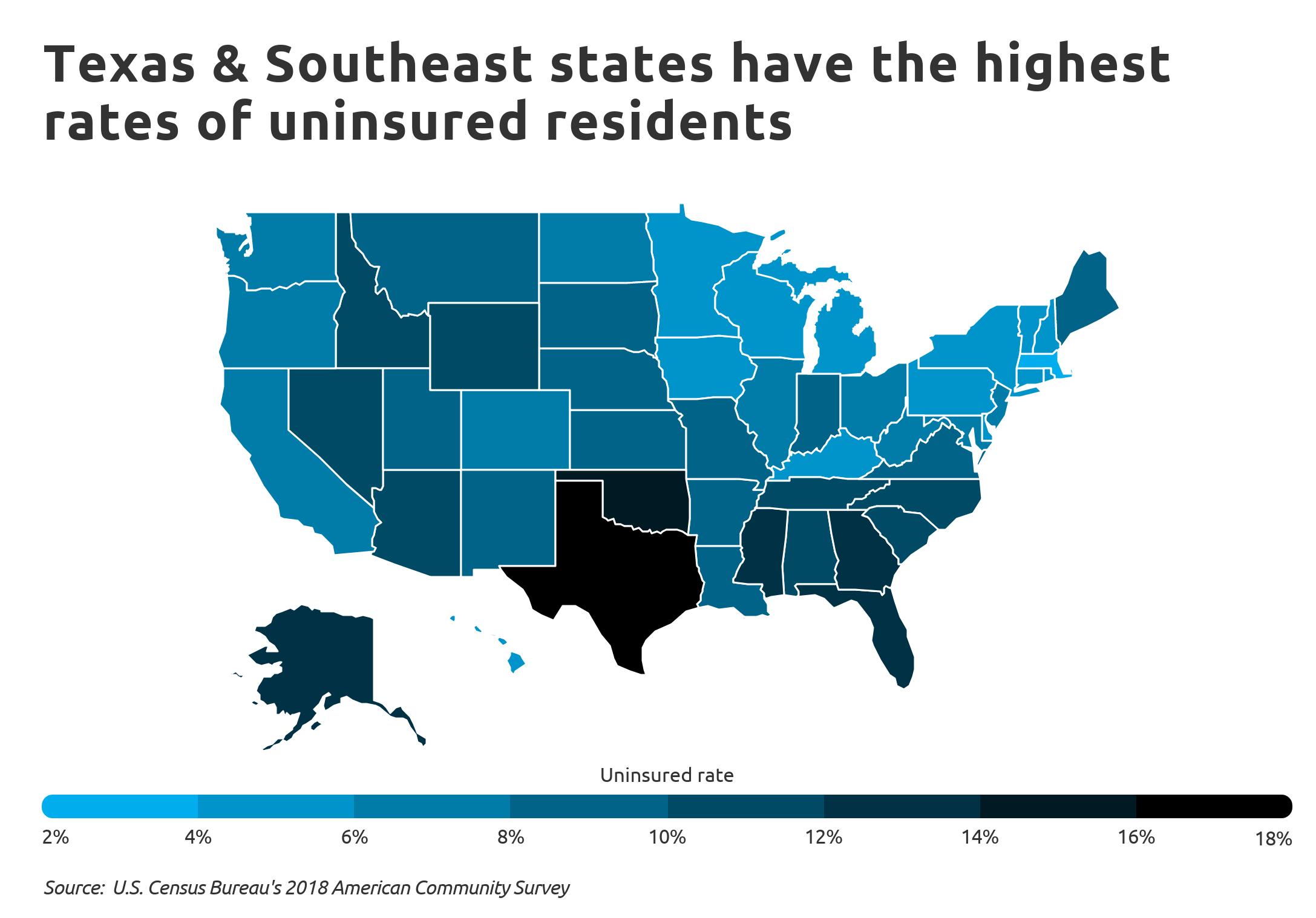

Texas has the highest uninsured rate in the U.S., with 29 percent of adults uninsured as of May, according to a report from Families USA.

The report compared uninsured rates in 2018 to rates in May 2020 using data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Urban Institute. Every state saw an increase in the number of uninsured, and the total number of uninsured in the U.S. climbed 21 percent.

The increase was due in part to layoffs tied to the COVID-19 pandemic in recent months. Nearly 5.4 million Americans lost health insurance coverage from February to May of this year due to job losses, according to the report.

Below is the total percentage of all uninsured adults in each state and the District of Columbia as of May.

Texas: 29 percent

Florida: 25 percent

Oklahoma: 24 percent

Georgia: 23 percent

Mississippi: 22 percent

Nevada: 21 percent

North Carolina: 20 percent

South Carolina: 20 percent

Alabama: 19 percent

Tennessee: 19 percent

Idaho: 18 percent

Alaska: 17 percent

Arizona: 17 percent

Missouri: 17 percent

Wyoming: 17 percent

New Mexico: 16 percent

South Dakota: 16 percent

Arkansas: 15 percent

Kansas: 15 percent

Louisiana: 14 percent

Virginia: 14 percent

California: 13 percent

Colorado: 13 percent

Illinois: 13 percent

Indiana: 13 percent

Maine: 13 percent

Montana: 13 percent

New Jersey: 13 percent

Oregon: 13 percent

Utah: 13 percent

Michigan: 12 percent

Nebraska: 12 percent

Washington: 12 percent

West Virginia: 12 percent

Delaware: 11 percent

Maryland: 11 percent

New Hampshire: 11 percent

North Dakota: 11 percent

Ohio: 11 percent

Connecticut: 10 percent

Hawaii: 10 percent

Kentucky: 10 percent

New York: 10 percent

Pennsylvania: 10 percent

Wisconsin: 10 percent

Iowa: 9 percent

Rhode Island: 9 percent

Massachusetts: 8 percent

Minnesota: 8 percent

Vermont: 7 percent

District of Columbia: 6 percent